Deborah Dearing designs great places

Watch the video: Deborah Dearing

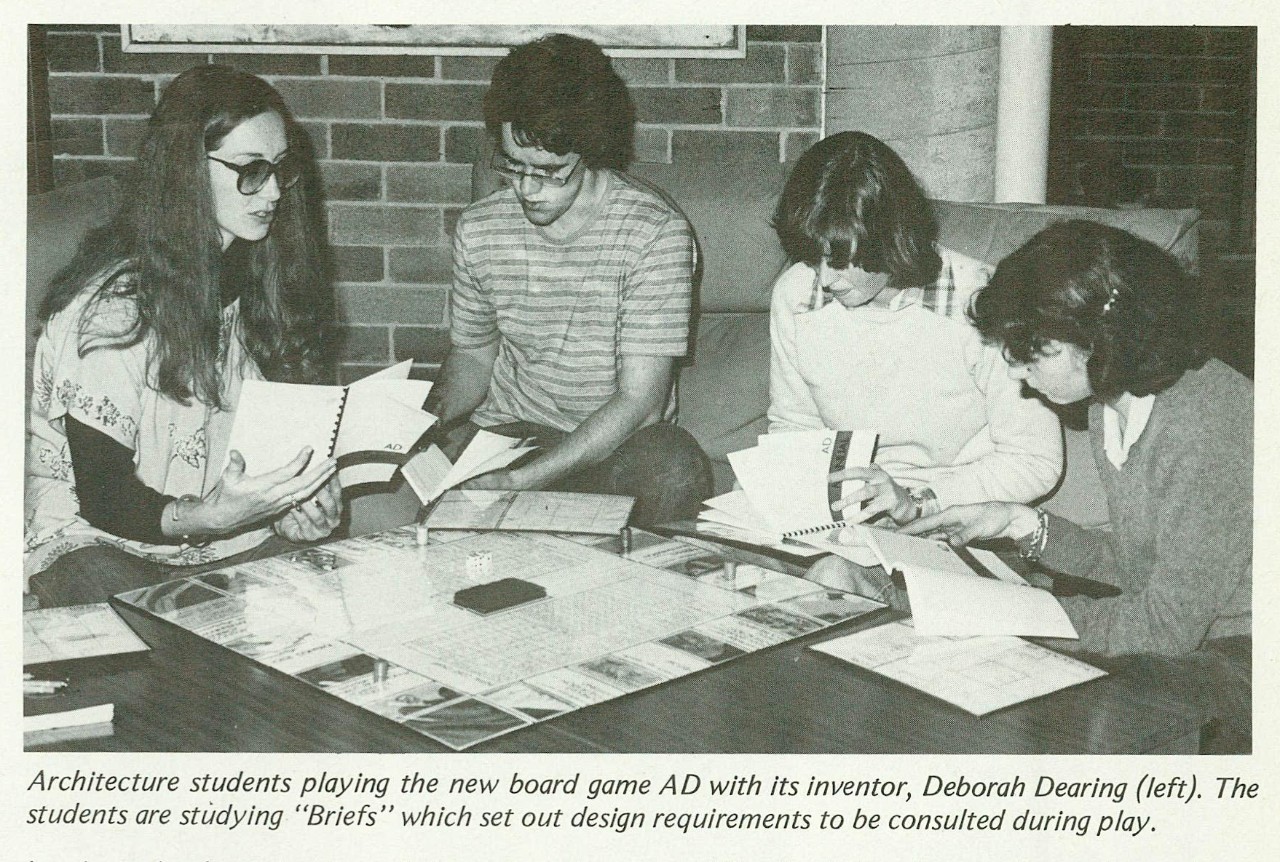

After studying architecture at the University of Sydney in the 1970s, an ambitious young Deborah Dearing set off to Denmark to study urban design with Jan Gehl. A relatively new field at the time, Deborah brought what she learned back to Sydney and began convincing Australia’s built environment sector of the need to consider the spaces between buildings.

Now the District Commissioner for the North and Eastern City regions of the Greater Sydney Commission, Deborah is also President of the Architect’s Registration Board in NSW, a member of the NSW Heritage Council and this year won the prestigious Australian Institute of Architect's President's Prize (NSW) for outstanding leadership and continuing contribution in improving the design quality of cities and communities. With over 30 years of international experience in urban design, strategic land-use planning, and affordable housing development in both public and private sectors, we interviewed Deborah to find out more about her incredible career.

What was it like to study architecture at the University of Sydney in the 1970s?

It was quite intimidating to be quite frank. It was radical, it was dynamic and there was a great combination of diverse opportunities at the school.

The Tin Sheds had fabulous art teachers, Lloyd Rees was here as one of the lecturers and he had a huge influence on the whole faculty. A brilliant man and a wonderful inspiration for everyone. But then we also had excellent design tutors who were the crème de la crème of Australian architecture. Glenn Murcutt was teaching and so was Keith Cottier, from Allen Jack+Cottier Architects, both of them brilliant designers.

At the time the university was developing its focus on architectural science and we were very fortunate to have Henry Cowan, who established the architectural science courses here. John Gero was also building a computing science capability, that was quite exceptional at the time as most universities didn’t have those resources.

It was in the throws of moving from these huge two-story shed-like structures, into this new building designed specifically for the architecture school.

We had much small, intimate tutorial groups and the discussions would be quite intense about what was important in architecture, what one wanted to get out of it, how one could express the context of the place and the challenges the designers were facing.

How did you get into urban design?

My interest in this area developed when, after finishing university here, before I went overseas, I had been working on the High Court Building in Canberra. One of the tasks I had was working in a little group designing the timber joinery internally. We would spend days and weeks designing a small component of a building. The amount of design effort that went into every part, it’s absolutely critical to deliver a high-quality building, but I just thought, there are bigger issues from an architectural design perspective than internal fit-outs or the pristine finishes of one particular building. Yes it’s important, but that future wasn’t for me. I wanted to have a more holistic, expansive role in the development of cities.

Royal Danish College of Fine Arts

When I left the university, I had been given a scholarship for Woman Graduate of the Year, which was a hugely generous amount of money. I can’t recall who actually recommended it to me but they said, look, there is a guy in Denmark called Jan Gehl – if you go and study with Jan Gehl that would be worthwhile and you may find that really interesting. Which I did. So I went and joined the urban design course at the Royal Danish College of Fine Arts.

What did you learn from Jan Gehl?

Urban design was very much about, not just the design of objects, or architecture per se, but the design of cities. A key component in developing great cities, is understanding design on a much broader scale than an individual building. We need to think about design in terms of integrating demands. In the same way that a house demands a living room and facades and roofs and circulation systems, cities also have to take into account very similar characteristics, using different materials.

Understanding how great places are made is more than just an ad hoc combination of buildings and floor spaces and heights. It’s very much an intentional process which says, we need to analyse where the wind is, where the sun is, where the landscape should be- that’s very much urban design. We also need to understand the users of the city: if you were designing a house for people you would really want to know who you are designing for and, how do they live? When we look at cities we need to be thinking, what public spaces work? What attracts people to stay there and not just walk through places? How do we make them function optimally, for the whole community?

How did you end up back in Australia?

I eventually ended up working in urban design in Zurich, Switzerland and I had decided to apply for a role in city design in Lucerne. In the interview I was told that my CV and experience were better than anyone else who had applied, in those days you couldn’t study urban design in Switzerland either, it was a relatively new field even in Europe. They said they were keen to get that expertise on board, but they couldn’t offer me a job as I was a woman. In Australia that was probably illegal at the time. It wasn’t in Switzerland and there were areas in Switzerland at the time where women still weren’t able to vote.

So, I decided to move back to Sydney and I brought urban design back with me, as it was my passion. When I came back, trying to work in this field wasn’t easy either as there weren’t many urban design projects being commissioned. The field of urban design in Sydney did eventually grow and it’s now much more a part of architecture, design and planning.

Why did you decide to complete your PhD at Sydney?

I had applied for a grant to write a PhD at the University of Sydney and what had interested me were the differences between where I had worked in Europe and, trying to work in urban design in Sydney, why attitudes were as they were. It was the early ‘90s and the attitude in Sydney was that, in terms of urban development, city expansion and development can not be limited. What I found fascinating was in Switzerland, where land is extremely constrained, they certainly limit city growth and don’t allow it to sprawl out into the suburbs for kilometres and kilometres. I had other questions such as, analysing whether it was true that Australians don’t want to live in apartments, that they all want a detached house.

I decided I would like to challenge some of these common assumptions playing out in Sydney. My PhD crossed the boundaries of architecture, urban design and planning and I wanted to do it at the University of Sydney as Peter Webber was here, and he himself worked across architecture, urban design and urban planning.

Tell us about an urban design project you’re especially proud of?

One of my favourite projects is the Stockland Balgowlah development.

When I first came onto the Balgowlah project, we engaged a group of talented consultants, including Keith Cottier as lead architectural designer, and we worked hard to deliver a range of outcomes that the community was happy with.

We wanted to develop a place where the community enjoyed the outdoor areas as much as they enjoyed their apartments. We also wanted to develop a high-density residential area with retail and community facilities associated with it, but in a format that didn’t rely on a simply having a 20 or 30 storey tower. We’ve used a range of different heights in this project from two, three and four storeys, up to a maximum of eight, and the densities we’ve achieved are roughly the same as a tower would have delivered, but in a way that’s more human-scaled and designed to support community interaction. People want private, semi-private and communal spaces. People want places where they can get together and places where they can be secluded.

Stockland Balgowlah

One of the attributes of this site is the fact that the community can access spaces which are often privatised in major developments. We want them to be able to walk through on their way to the shops and feel welcome within the garden areas. It’s all about the scale: the garden areas aren’t massive but they are both public and private.

The project is nearly 10 years old now, but the landscaping looks far more mature. That’s because we purchase the trees as mature specimens while construction was underway. That’s important to the quality of life and the usability of the spaces.

How do you see the profession of urban design evolving over the next 100 years?

I would like to see the profession evolve with a greater awareness of the need for careful design consideration of the spaces between buildings, and the need to integrate a range of different stakeholders into the design process so that they can take ownership.

We need to develop a holistic integrated model which actually optimises urban opportunities through evolution and through change, rather than looking at things as insular component, for example: transport issues, infrastructure issues such as health and schools, and then looking at housing issues separately.

And the goal at the end of the day is to build great places, as Sydney grows, and that we know the Sydney of the future is as much admired and loved as it is today.