China's TV dramas: exploring the popularity of Xianxia

Dr Yu Sang from the School of Languages and Culture explores how China’s Xianxia TV dramas, a growing pop culture phenomenon in the country, are inspiring contemporary citizens to reconnect with classical traditions.

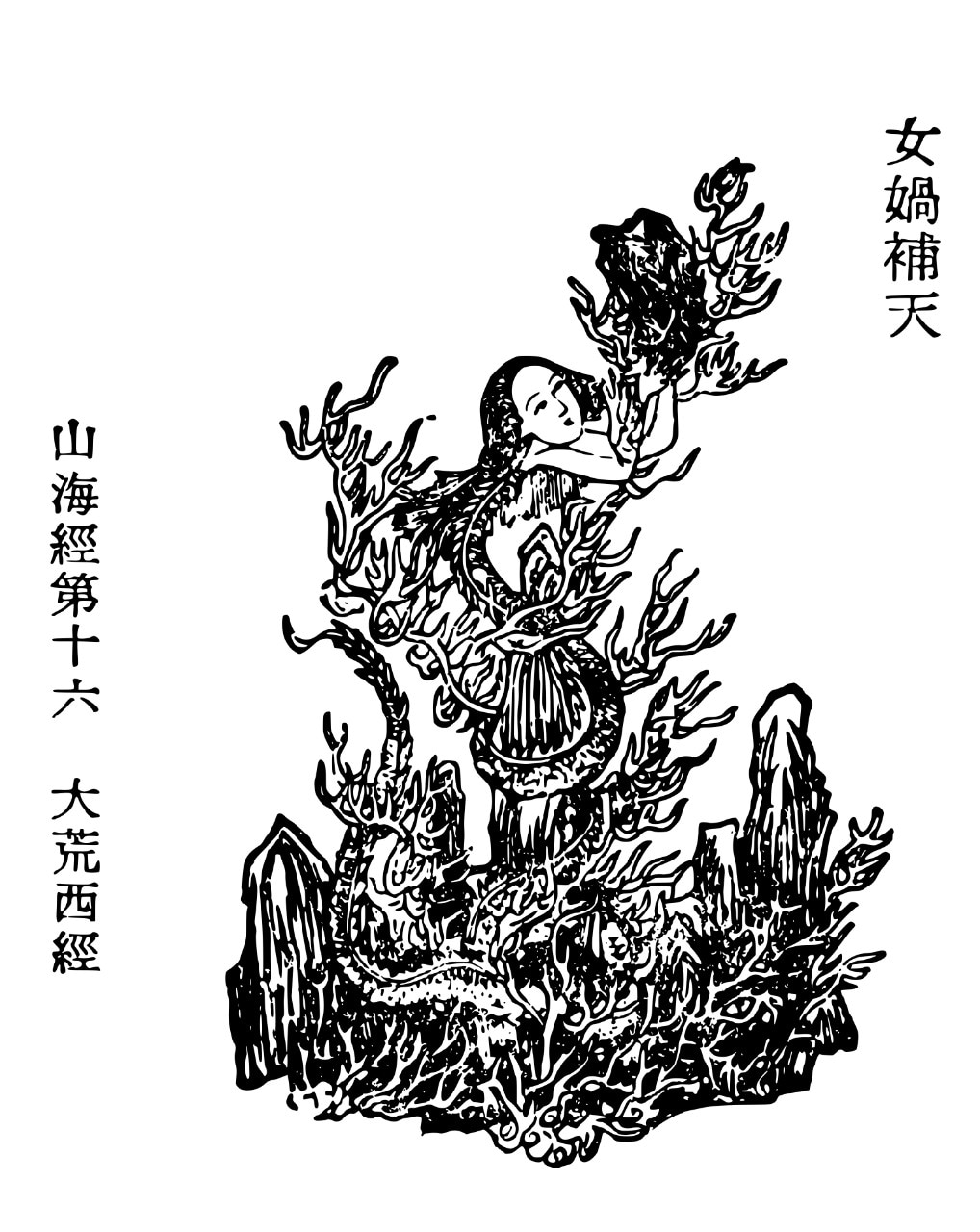

The Xianxia genre is thought to have originated from the ancient text Shan hai jing, which tells the story of goddess Nuwa. She is depicted here 'mending the heavens'. Credit: Public domain, Xiao Yuncong, 1596-1673

‘Xianxia’ (meaning ‘immortal heroes’) is a fantasy TV genre based on Chinese mythology and the concept of chivalrous spirit. In recent years, Xianxia dramas have become a huge pop culture phenomenon in China. The internet is full of ‘top 10’ Xianxia series lists. Many Xianxia dramas have been widely discussed and debated by their audiences, and songs from the dramas have also become very popular. Fans have even emerged outside of China. Notably, the dramas have helped to revive classical Chinese dress in high fashion, pop culture and cosplay spheres.

However – more broadly, and perhaps more significantly – they have also aroused widespread interest in traditional Chinese culture and thought, which constitutes the basis of Xianxia stories, ideas, and beliefs. This contemporary revival of Chinese tradition speaks to the ongoing relevance and appeal of its philosophical cornerstones, which have transcended millennia to inspire the audiences of today.

Where did the Xianxia genre come from?

The Xianxia genre can be traced back to early Chinese literature, in particular the ancient text Shan hai jing (Classic of Mountains and Rivers). Its famed story of Nuwa, a goddess in classical Chinese mythology who is credited with creating humans and mending the sky, is popular among the dramas. This is especially conspicuous in the TV show Xianjian qixia zhuan (often translated as ‘Chinese Paladin’ in English), broadcast in 2005, which is considered to be the genesis of the Xianxia genre of TV dramas in China and has influenced its development. In it, the main female character, Zhao Ling’er, is described as the descendant of Nuwa who bore a mission to save her people from an evil cult and sacrificed herself for her kingdom at the end. A similar premise can also be seen in later Xianxia dramas, in which descendants of Nuwa are often endowed with a responsibility to protect the world.

It is not just classical literature that the genre draws from: traditional philosophy, too, plays a key role. Confucianism, Buddhism and Daoism have all been integrated into Xianxia dramas.

For instance, a well-known saying from Daoist philosophy is repeatedly mentioned in the 2016 TV show, Qingyun zhi (The Legend of Chusen): “Heaven and earth are not humane, taking the myriad things to be straw dogs”. This sentence originates in Daode jing

(The Book of the Way and Virtue), a Daoist classic composed by the ancient philosopher Laozi (traditionally understood to have lived between 6th–5th centuries BC). It expresses the idea that heaven and earth – devoid of personified human feelings – are not biased, and that the workings of the myriad things in the world only follow natural rules. The leading male character, Zhang Xiaofan, repeatedly ponders over this saying as part of his entanglement with the complexity of human nature and his evolving understanding of the question: what is good and what is evil? This question is also a core issue that the drama reflects on, exemplifying that xianxia works do not simply echo the classics but also explore their depths.

What qualifies a drama as Xianxia?

No matter what story a Xianxia drama tells, to qualify as Xianxia it must maintain a constant theme of using one’s own power to punish evil and praise good. The term Xianxia includes two parts: xian, referring to supernatural and immortal beings, and xia, meaning chivalrous heroes. The main characters in xianxia dramas typically have strong minds and great personalities. They may be weak at the beginning, but they are never afraid of a challenge. During their growth, they usually have unbelievable adventures and opportunities which make them stronger and eventually allow them to defeat their enemies.

The ultimate purpose of Xianxia characters, as heroes with extraordinary strength, is normally to guard all people – a concept expressed in Chinese as cangsheng. Similar to Western superhero narratives, such as those of Spider-Man and Captain America, a core belief in Xianxia stories is that “with great power comes great responsibility.

For example, in the 2015 drama Hua Qiangu (The Journey of Flower), this concept is a belief of the main male character Bai Zihua, leader of an immortal sect, while his sole disciple Hua Qiangu, the main female role, repeats it regularly as her motto.

Yet another archetypal element in Xianxia dramas is, of course, romance. When Xianxia heroes have completed their tasks, Xianxia narratives often see them go away and live in seclusion with their lover, who usually is another main character in the drama. This romantic ideal can be loosely expressed in Chinese with the line, “When all is done, [the knights-errant] swing their robes and leave, keeping their achievement and fame deeply hidden”. This sentence originates in the poem, Xiake xing (The Poem of the Knights-errant), composed by the famous Chinese poet Li Bai (701–762) in the Tang dynasty (618–907). The latter half of the sentence, a phrase meaning ‘hiding achievement and fame’, has become an internet buzzword – showing yet again how age-old Chinese concepts are finding renewed resonance within society today.

A celebration of traditional Chinese culture and values

Chinese culture has a long history, and its contemporary resurgence has been partly achieved through the popularity of Xianxia TV dramas. To understand Xianxia characters and their worlds as well as their appeal today, we need knowledge of classical Chinese mythology and philosophy. As its values have influenced a large number of people in the world, Chinese culture is well worth exploring. Why not start by watching a Xianxia TV drama?

Author, Dr Yu Sang

Dr Yu Sang is an Academic Fellow in Chinese Studies at the School of Languages and Cultures. She researches Chinese philosophy and religion and is also interested in the relationships between Chinese traditions and contemporary society.

Top photo: People cosplaying in Xianxia style. Credit: Rico Lee, Flickr