Awake to possibilities

A population that sleeps well is healthier, more productive and less accident prone. The Sleep and Circadian Research Group has an ingeniously designed facility for studying sleep and helping those with sleep disorders.

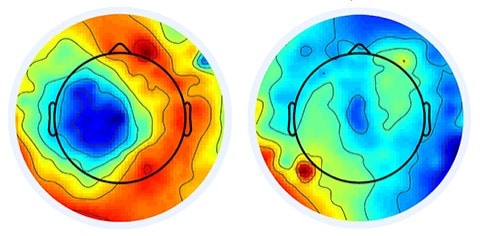

Topographical brain maps during sleep (left) and wakefulness (right).

Sleep. We all do it. We don’t all do it well. And according to Professor Ron Grunstein (MD ’95 MBBS ’80), some of us keep ourselves awake worrying about it.

“Telling people they must get eight hours’ sleep creates insomnia,” he says with a smile. How much sleep to get is the question Professor Grunstein is asked more than any other.

“It varies,” he says. “Most people sleep from six-and-a-half to eight hours a day. You wouldn’t call lack of sleep ‘insomnia’ unless it really affects how you work and live. That happens to about 10 per cent of the population.”

Professor Ron Grunstein.

During the day, the 12-bed sleep accommodation feels strangely vacant, but at night it’s buzzing with clinicians and the sleep disturbed: men, women and even children with conditions such as narcolepsy, circadian rhythm disturbances, and the second most common sleep disorder, sleep apnoea.

The Woolcock’s sleep research unit is Australia’s only multidisciplinary sleep centre dedicated to understanding and treating sleep disorders, with researchers drawn from diagnosis and molecular biology through to drug development, disease management and sleep education. Walking into reception, it feels like a pleasant, mid-ranking city hotel, but the Woolcock offers a lot more than a bed for the night.

“We have an area where we can isolate some of our patients from time,” Professor Grunstein says. “This lets us observe their actual sleep patterns by removing the cues that tell them what time of day it is.”

This includes floors built on springs to absorb vibration from morning garbage trucks; food is continuously available so there’s no sense of breakfast, lunch and dinner; light from any time of day can be mimicked in the rooms, and there’s no internet or television. Male technicians even have to make sure they shave at random times.

Dr Maria Comas Soberats.

The body clock, also called the circadian clock, is involved in more than sleep. It also affects behaviour, physiology and metabolism, such as eating patterns. “The richest results come when sleep disturbance and body clock studies inform each other,” Professor Grunstein says.

Which is why he jumped at the chance to bring Dr Maria Comas Soberats onto the team.

Recently arrived from Sweden, Dr Comas is a postdoctoral fellow and molecular chronobiologist who has worked with world authorities in the body-clock field. She is also an awarded researcher. “I am passionate about my work,” she says. “There is so much to learn. For example, people with schizophrenia or other severe mental illnesses have chaotic body clocks. Understanding more about their clock function could lead to better treatments.”

There is even the promise that cancer clinicians could use Dr Comas’s insights to make existing treatments more effective.

“Every cell in a person’s body has its own clock,” she explains. “A red blood cell doesn’t even have a nucleus, but it does have a clock. The clock activates and represses functions within that cell.

“So if a cancer drug is designed to be taken up by a particular receptor in a cell, it will be much more effective if you can administer it when you know the cell clock has made that receptor active.”

This implies using a different mindset in some cancer treatments so the body clock is considered when designing therapies. What’s always needed is more information, and Dr Comas is excited about what will be uncovered in this area.

“Professor Grunstein is helping me make connections here at the University with researchers in other fields. They really want to be involved,” she says. “I’ve worked where people talk about collaboration but it doesn’t happen. Here it does. It makes so much more possible.”

Written by George Dodd

Photography by Louise Cooper