Sound with vision

It's often called the bionic ear, but Professor Graeme Clark first thought of it as the cochlear implant. His invention has now been changing the lives of deaf people for decades, but it faced strong, early opposition from the medical establishment.

Search “hearing for the first time” on YouTube and you’ll find a video of 21-year-old Raia, who started to lose her hearing at the age of two. The video was made when her new cochlear implant was activated.

As she realises the implant is working, Raia wants to laugh with joy, but she is so overwhelmed by what’s happening she begins to sob. She covers her mouth as the tears flow and tries to laugh again, but she can’t. Having this new sense, that so many of us take for granted, is about to profoundly change Raia’s life and how she connects with everyone she knows.

There are many more videos online of people like Raia – men, women and children experiencing hearing for the first time. They’re part of a community of more than 320,000 people around the world whose lives have been transformed by the inventor of the cochlear implant, Professor Graeme Clark (MB ’58 MS ’69 PhD(Medicine) ’70 MD ’89).

Professor Graeme Clark

He, of course, was often present as people heard their first sounds. “It’s a very moving experience,” he says in his measured and gentle tones. “It brings tears to my eyes still.”

It’s been said that the cochlear implant is the only real advance in hearing technology since the 17th century and the ear trumpet. Even electronic hearing aids are just a sophisticated version of that. Rather than channelling sound into the ear canal to, in effect, be louder, a cochlear implant converts sound into impulses then uses them to stimulate the auditory nerve directly. This bypasses damaged parts of the ear to carry sound signals to the brain.

Professor Clark’s journey towards the cochlear implant started in one of the labs in the University’s Anderson Stuart building. “That building means so much to me,” he says fondly. “It was there that I developed key research that showed we needed to use multiple electrodes to replicate sound.”

By the late 1970s he was well advanced with his design but, like many innovators, he was meeting strong, early opposition from his peers. There was even talk of forcing him to resign from his new role as Australia’s first professor of ear, nose and throat surgery.

In his office, Professor Clark still has the magnetic reel recording of the second cochlear implant operation he performed.

“They referred to me as ‘that clown Clark’,” he says without rancour. “One of my colleagues – this was reported back to me by one of my friends – said that I would kill my patient.”

The pressure on Professor Clark was enormous, but he had faith in what he was doing and worked hard to make his idea work. His cochlear implant wasn’t just a feat of medicine and surgery. To make it a reality Professor Clark had to become adept at electronics, physics and engineering. He spent countless hours in the lab and the library, but one of his most important breakthroughs, to do with the cochlea itself, happened at the beach.

“Cochlear” is the Latin word for snail shell and that’s what it looks like: a snail shell about the size of a pea, and just a couple of millimetres wide at its widest point. For his idea to work, Professor Clark had to thread a super- ne wire into this tiny spiral cavity so it could be used to stimulate the cochlear’s array of 20,000 sound-receiving nerves. Frustratingly, he was having problems getting the wire to go around the spiral.

We all stand on other people’s shoulders and see further ahead.

“I was sitting on Minnamurra Beach near Kiama in New South Wales,” he recalls. “I was playing with a shell that had the same spiral structure as the cochlear, and I realised I could get a blade of grass to do what I needed the wire to do. The flexibility in the tip of the grass enabled it to negotiate around the turns of the shell. That was a flash of good fortune.”

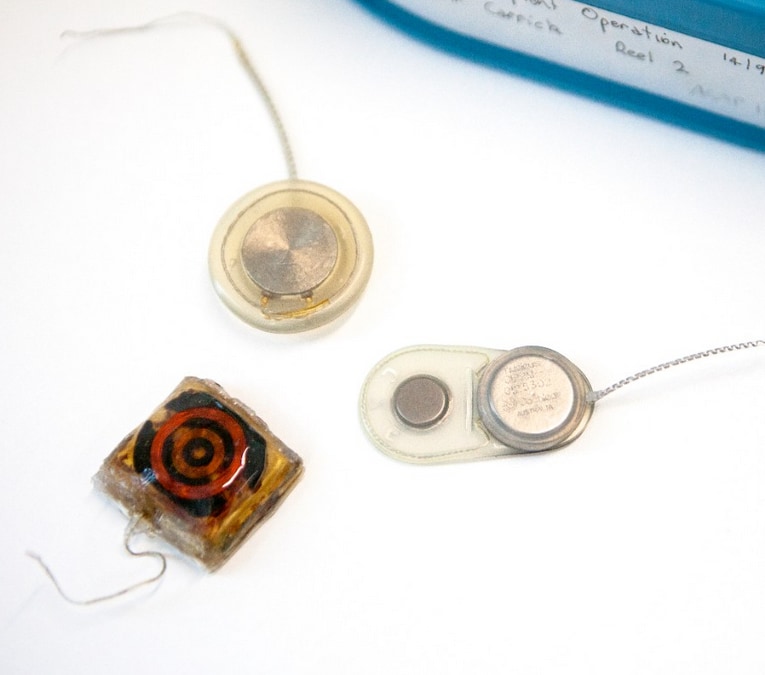

The first commercial implantable bionic ear, Cochlear's mini bionic ear with magnet to hold the transmitting aerial in place, the first prototype.

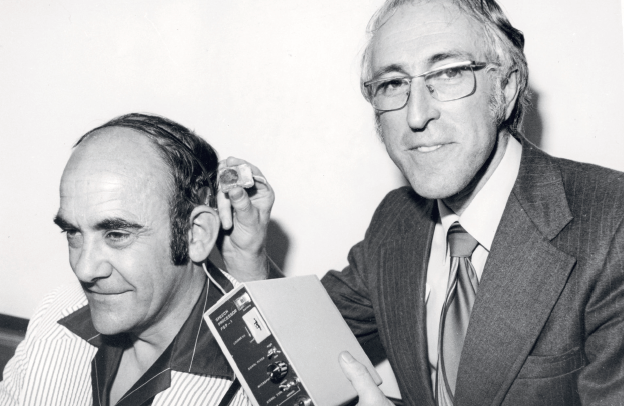

Even as the implant design came together there was still a major hurdle to overcome. The disapproving medical fraternity was refusing to refer likely candidates for the procedure to Professor Clark. Finally, two candidates emerged and one of them, Rod Saunders, went on to become the first person in the world to receive a cochlear implant in 1978. In fact, it was the first time anywhere in the world that such a complex set of electronics had been implanted in a human.

Still, the success of the first operation didn’t turn the tide of disapproval. While individual surgeons began doing the procedure, the mainstream still rejected it. But the potential benefits of the implant, which came to be known as the bionic ear, were undeniable. So, in the early 1980s the federal government partnered with a medical device company to bring the implant to the market.

As a five-year-old, Professor Clark was already telling his kindergarten teacher that he wanted his job to be fixing ears. His motivation was seeing his profoundly deaf father struggling to communicate with the customers in his pharmacy business. From that time on, Professor Clark’s medical ambition was unwavering and he has transformed an entire area of medical science. His technology is still evolving and it has inspired a new field of research called medical bionics, which is generating ideas around bionic eyes and spinal cords.

Made profoundly deaf by an accident, Rod Saunders (left) was Professor Clark's first cochlear implant recipient.

Now in his 80s, Professor Clark still works at the Centre for Neural Engineering at Melbourne University, advancing bionic technologies. Talking to him, he is aware of his achievements but without any sense of ego.

“We all stand on other people’s shoulders and see further ahead,” he says after a conversation where he has referred with true admiration to colleagues and past lecturers who made it possible for him to achieve what he has. “Ultimately, it’s about the benefit it brings to people and seeing the joy that they experience.”

Written by George Dodd

Photography by Adam Luttick