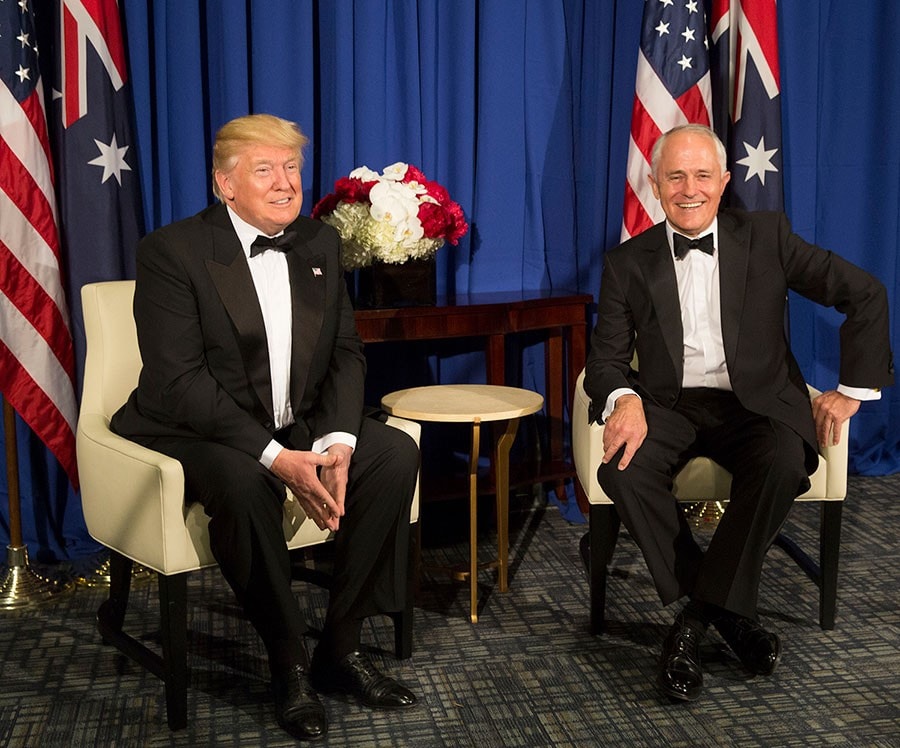

Malcolm Turnbull's ANZUS offer on North Korea was premature

Invoking the ANZUS treaty was unnecessary, writes Professor James Curran for the Australian Financial Review.

Image courtesy Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

Prime Minister Turnbull's pre-emptive invocation of the ANZUS treaty during a radio interview last Friday was not only extraordinary and unprecedented, it was also premature and unnecessary.

Two problems in particular stand out.

The first is that the comments, even if unwittingly, contributed to the escalatory tempo of a week in which the rhetoric flying between Pyongyang and Washington was already red-hot.

No-one doubts that the US and Australia share common cause in wanting to see the crisis on the Korean peninsula resolved peacefully. But instead of adding to the talk of war, Turnbull would have been wiser to stick to his foreign minister's script – stressing the continuing need to put the Australian shoulder to the diplomatic wheel. It was perfectly reasonable, then, for the New Zealand Prime Minister Bill English to stress that any such US request would be assessed "on its merits".

Reserving the right to decide

Talk of Australia's continuing legal obligations under the terms of the 1953 armistice is not altogether idle, but as the analyst Andrew Selth pointed out some time ago, such historical precedents or "outdated" legal instruments "may be cited for diplomatic or other reasons, but Canberra would make its final decision based on all the factors – both domestic and international – that were relevant at the time".

The second is that in the event of any crisis, Turnbull has now locked Australia in and diminished its freedom of movement. Most crucially, by enunciating his intent in public, he has virtually sacrificed the ability of Australia to judge and then act on its own interests. In short, the Prime Minister's remarks offer the US a blank cheque.

But as many have pointed out in recent days, the treaty is not an automatic trigger for military assistance on either the part of Australia or the United States. Articles III and IV of the treaty stipulate only a commitment to consult and for each party to "act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional processes".

Things best left unsaid

Prime Minister Robert Menzies and President John F. Kennedy

Photo by Abbie Rowe and Robert Knudsen via Wikimedia Commons.

It is true that Turnbull's hedge was important in this regard: he was emphatic that Australia's ANZUS obligations would only come into effect in the case of clear-cut aggression against the US by North Korea. Few can doubt that in such circumstances, the alliance DNA coursing through the Australian strategic bloodstream would see a government in Canberra offer some kind of military support to America.

Notable too is Turnbull's equal emphasis on Australia's expectations of US military support if the situation was reversed. Again, if there was a naked and unprovoked attack against this country, the Americans would have little option but to invoke ANZUS and come to Australia's aid. But Turnbull's formulation perpetuates a simple-minded insurance premium view of the relationship – the idea that just because Australia offers Washington unflagging support at every turn, its great ally will return the favour come what may.

But what are the historical grounds for believing loyal support for a great power ally or any ally will be reciprocated when the country giving the support is in need?

As the history of the alliance shows, rarely are the circumstances pertaining to possible invocation of the treaty so clear – John Howard's invocation of ANZUS after 9/11 being the exception.

Defining expectations a bad idea

In the past the Americans have done much to water down their interpretation of US obligations under ANZUS. Immediately after the terms of the treaty had been settled in early 1951, the chief US negotiator John Foster Dulles advised General Douglas Macarthur that "under the terms of the treaty the United States can discharge its obligations ... in any way and in any area that it sees fit." Over the succeeding decades the Americans have, understandably, acted in full accord with that spirit.

Thus when the Australian leaders repeatedly asked the US for military assistance in the event of possible armed conflict with Indonesia during the Confrontation episode in the early 1960s, they never quite got the response they were looking for. As John F Kennedy put it bluntly when asked if Washington would be automatically engaged under the terms of ANZUS, "this is not what the United States thinks."

Indeed, so relentless had Canberra's request for a stronger security guarantee become, and so continuously disappointing had been the American responses, that by the mid-1960s external affairs minister Paul Hasluck remarked privately that the best policy for Australian ministers in regards to America's ANZUS commitments was to simply keep quiet. "The more we try to spell out the meaning" for them, he wrote, "the narrower that meaning will become." And, crucially, he added that "it will be much harder for any United States government to try to whittle down the meaning of its promises in the hour of crisis than to try and whittle them down around a conference table before the crisis has been reached."

This is why successive Australian governments have largely refrained from articulating in public their view of what they think the treaty obliges their great power ally to do.

What is certain, however, is that when Turnbull told Trump at the end of their testy phone call in January that "you can count on me", he meant it. Ever since, he has looked for the right moment to honour that pledge. But last Friday he picked the wrong time and the wrong way to do it.

Professor James Curran is a historian specialising in the history of Australian and American foreign relations at the University of Sydney. This article was originally published in the Australian Financial Review.