What the doctor ordered

From the bitter cold of Antarctica to the scorching sun of Jordan, Dr Gillian Deakin has always taken her extensive medical knowledge and skills where they'll do the most good. This is a doctor with a difference.

Dr Gillian Deakin has a human approach to medicine, and an intrepid approach to life.

Not every job requires you to have your appendix removed, but that’s exactly what happened when Dr Gillian Deakin (MBBS ’81 MPHlth ’90) applied for the position of doctor and medical researcher on the Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition in 1984.

She didn’t think it likely she’d be accepted, given very few women had wintered on the Antarctic continent before, but when she was called for an interview, she saw before her the opportunity of a lifetime. “I had always wanted to be a ship’s doctor and I love the ocean,” she says.

“Crossing the Southern Ocean to see the midnight sun then experiencing the extremes of a polar winter was just the sort of adventure I was looking for.”

With her appendix removed – required because a previous doctor had been forced to remove his own in the depths of winter – Dr Deakin set out as the only woman among a team of 100 men, not only completing the research required for her medical degree, but also assisting the expedition’s vet with his research into the seal and penguin populations.

Medicine, for Dr Deakin, never conjured up an image of sitting behind a desk. Instead it was synonymous with adventure. She had plenty of inspiration from a long line of doctors in the family, and knew it to be a profession that could take her anywhere and everywhere.

For a time, Dr Deakin (third from left) was personal physician to a Bhutanese princess. Seen here with a group of local nuns.

Having completed a doctorate based on her cardiovascular research in Antarctica, she enrolled in a Master of Public Health at the University.

Her first child, Felix, was just four days old when he came to classes. “I became very good at typing with one hand while breastfeeding,” Dr Deakin says with her characteristic good humour. “There was a lot going on but I loved the University life from day one.”

Aside from adventure, Dr Deakin thrives on the constant learning processes and challenges that medicine presents, a quality she recognises in her daughter, who is now also a doctor. But she also chose medicine in passionate pursuit of social justice: “I just thought that’s what an education was for,” she says. “To right the wrongs of the world.”

She credits her parents and the nuns who schooled her in the 1970s for instilling this idea. She vividly remembers the nuns inviting guest speakers to the school, such as Aboriginal activist Gary Foley who spoke about the Stolen Generations, and Mother Teresa detailing life in the slums of Calcutta.

After completing her master’s degree, Dr Deakin went to work in the Pacific island nation of Kiribati, which at that time had the world’s highest rate of an eye condition called xerophthalmia, which causes blindness.

This was due to a lack of vitamin A, partly caused by starchy foods that had replaced the traditional diet. Dr Deakin helped identify a local leafy green high in the vitamin, then worked with community leaders to incorporate it into everyday cooking. The growing rate of blindness was halted and the crop is still eaten to this day.

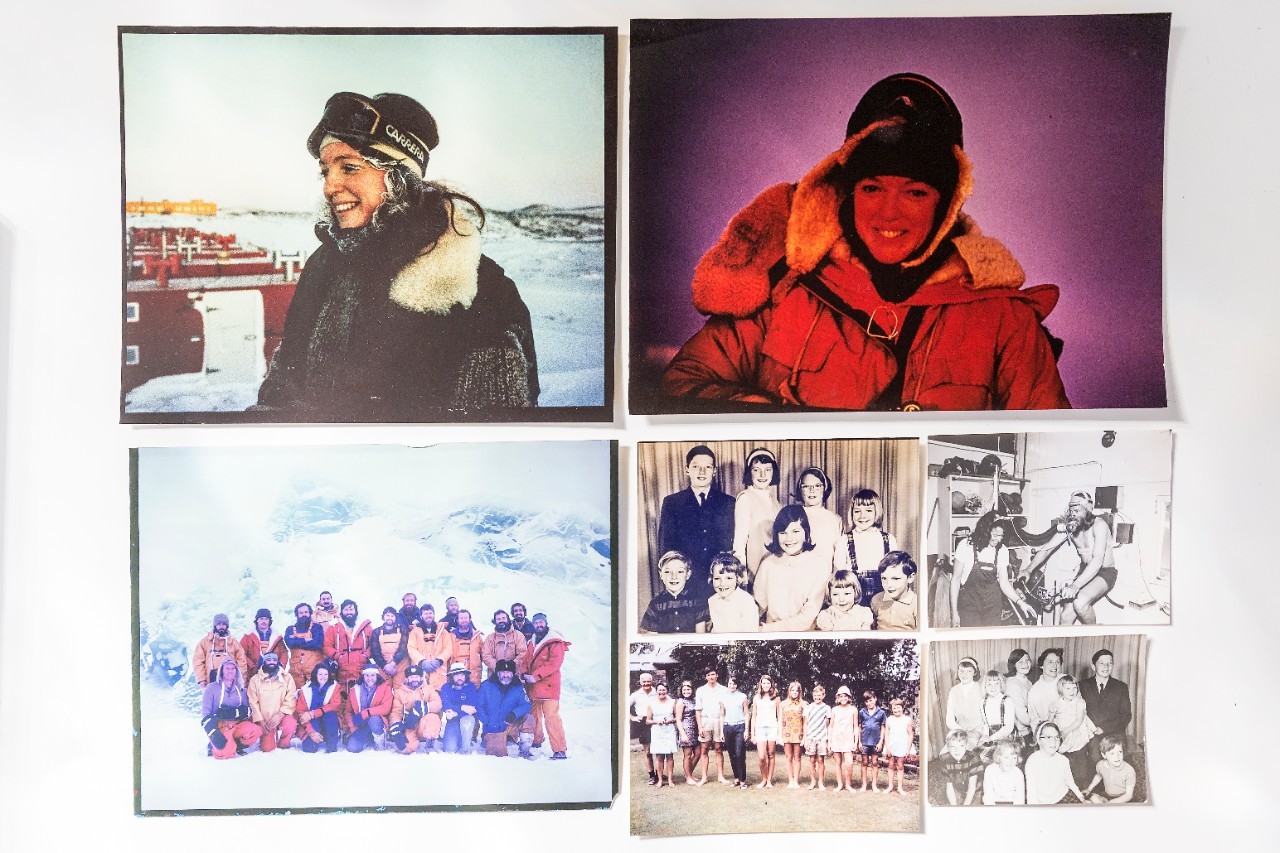

Memories of Antarctica 1984. Dr Deakin was determined that her career wouldn’t happen behind a desk.

Returning to Sydney, Dr Deakin worked in general practice and was involved in undergraduate and postgraduate training. In 2003, she joined efforts to prevent Australia’s participation in the invasion of Iraq and became vice-president of the Medical Association for Prevention of War.

In 2014, with her children now grown, Dr Deakin was ready for another challenge, and began working for Médecins Sans Frontières. First, she found herself in Russia working in a clinic for migrant workers from the war-torn areas of Chechnya and Kurdistan. She then moved on to Jordan and a 40-bed hospital in a refugee camp, where she treated people, including children and infants, who had sustained horrific injuries from bombing during the Syrian conflict.

For all her drive, Dr Deakin says she has never been ambitious in the usual sense. In fact, she turns the concept on its head. When confronted in her early career with competitive environments, she decided instead on paths that would take her “sideways” rather than up. For her, experiences were more important than status. While she was a successful student, she feels there is a limit to what books can teach. “You have to experience life if you want to be a doctor,” she says.

Dr Deakin would like to dedicate time to writing, which is one of her passions, and teaching. She also wants to work in the South Pacific region again. Conversation with her barely touches on her myriad past projects: her book, published in 2006; working in remote Aboriginal communities; and being the doctor on a film set in the Australian desert.

In email, almost as an afterthought, she writes: “I entirely forgot the time I was the personal physician to a Bhutanese princess [and] I did a bit of flying in my 20s … later did some work with the Flying Doctors.”

One can only imagine the adventures in between, and those still to come.

Written by Cybele McNeil

Photography by Matthew Vasilescu