Youth mental health: what's needed is more research

One in four young people will develop a mental illness, with half of those going on to have life-long challenges. In the past, treatment could be haphazard but the Brain and Mind Centre is advancing ideas to change that.

As the others at her school prepared for the HSC, Emerald was spiralling into depression, “I had so many beautiful things in my life, but I just didn’t want to be here.”

This wasn’t a new feeling for Emerald. She’d first been diagnosed with serious depression when she was just 14; a time when she was in such a dark place, she was a danger to herself. Over the next couple of years she spent time in hospital care, before going on to receive high level, though not always appropriate, treatment.

“The experience of being in hospital was harrowing,” she says. “There were people in there that were a lot sicker than I was, and sometimes I was really scared.”

While Emerald’s depression was severe, mental health issues are not rare in young people. One in four of them will suffer a mental illness, most often anxiety, depression, eating disorders, or psychotic symptoms. Half of those affected will develop life-long problems.

Giving young people the support they need

Still, governments can be unenthusiastic in their support of mental health treatment and research. Professor Ian Hickie is Co-Director of the University of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre and a commissioner on the National Mental Health Commission.

“If you look at national funding in health, it's dominated by cancer, diabetes and other issues related to ageing,” he points out. “Yet economically, the biggest costs are related to mental health, and actually the biggest cost is in young people.”

This means that the Brain and Mind Centre itself, largely relies on public donations to advance its work. A focus for the researchers now, is to make the treatments for young people less general and more tailored to individual needs. Ways of doing this are evolving with new technologies.

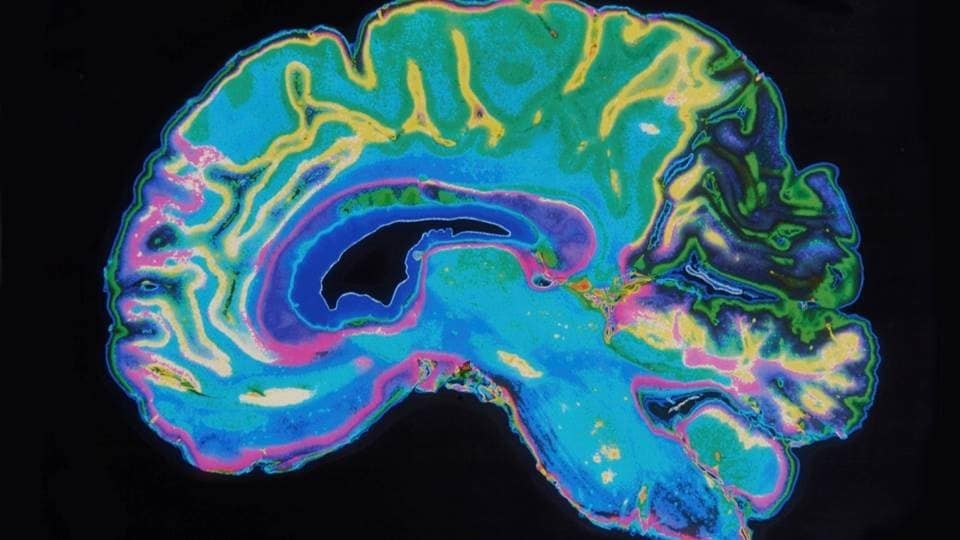

“We’re using brain imaging to see what’s happening on the inside, and we can manipulate the body clock hormonally,” he says. “The body clock actually changes in young people during major depressive and other mood disorders, so being able to fine-tune this for individuals is a very promising area of treatment.”

There are some very particular considerations when thinking about youth mental health. First, that up to the age of about 25, brains are still developing.

Professor Hickie points some of the questions this brings up for researchers, “What happens in the development of the frontal lobes during adolescence? What happens when that goes wrong? To what extent does the change in brain function lead to the sometimes severe mental health problems in young people?”

He then adds some of the external influences, “What are the social factors that are driving change - technology, alcohol and substance abuse, the expectations placed on young people?”

There is plenty to keep the Brain and Mind Centre researchers busy, but research is just one of a range of approaches being developed by the Centre. Another area already delivering results, is using the digital communication technologies that young people have embraced so whole-heartedly.

“Some people think young people over-use mobile phones and tablets,” Hickie says. “But this technology gives us a way of reaching young people in trouble, and connecting them with care, now - in real time, with real professionals. We've never had that opportunity before.”

There has already been significant success in the digital space through headspace Camperdown, which also provides face-to-face contact centres for young people, their families and friends. The headspace website provides online information and gives access to health professionals and counselling, as well as services that give support during schooling, study and work.

More than 250,000 young people in need of help have already used headspace. One of those people is Emerald, who is now 19 and in a much better place.

“I think I can say with confidence, that I wouldn’t have gotten to the point where I am now without headspace,” she says. “I know if I am in a crisis or whatever, I can go there and get some help.”

Professor Hickie knows how transformative the work of the Brain and Mind Centre can be in helping young people in crisis. He also knows what’s needed to make even more possible.

“We have a desperate need for new funding, innovation funding, breakthrough funding,” he says plainly. “So that we can make a substantial difference to the lives of young Australians.”

How you can help

If you would like more information on how to support the University of Sydney's Brain and Centre, please contact the development team online at sydney.edu.au/brain-mind/donate.