The latest Scientists' Warning (on affluence)

This Scientists' Warning, pre-COVID-19, prompts a re-think of affluence and growth. The explainer below pairs the new Nature Communications review that highlights the impacts of society's overconsumption.

Would you like to be rich? Chances are your answer is: “Yes! Who wouldn’t want to be rich?” Clearly, in societies where money can buy almost everything, being rich is generally perceived as something good. It implies more freedom, fewer worries, more happiness, higher social status.

But here is the catch: affluence trashes our planetary life support systems. What’s more, it also obstructs the necessary transformation towards sustainability by driving power relations and consumption norms. To put it bluntly: the rich do more harm than good.

This is what we found in a new study for the journal Nature Communications. Together with co-author Lorenz Keyßer from ETH Zürich, we reviewed recent scientific literature on the links between affluence and environmental impacts, on the systemic mechanisms leading to overconsumption and on possible solutions to the problem. The article is one of a series of Scientists’ Warnings to Humanity.

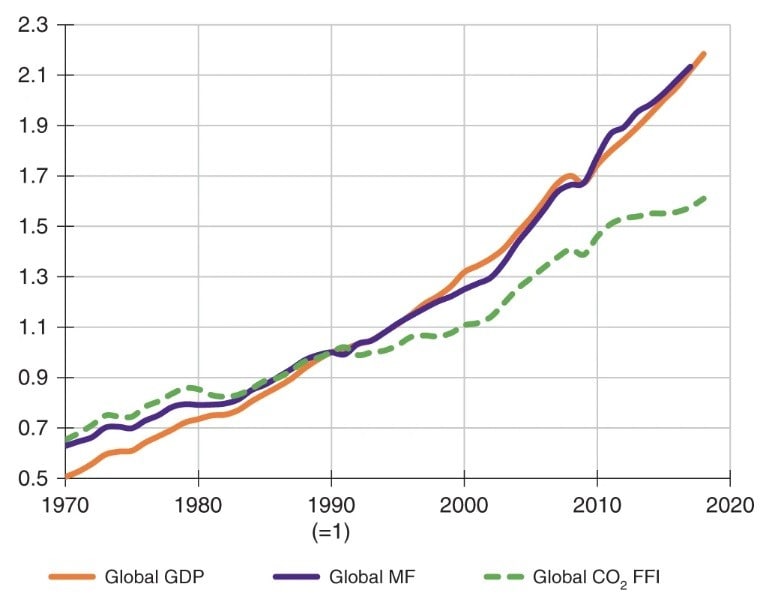

While technological improvements have helped... growth in affluence consistently outpaced these gains

The most affluent are most responsible

The facts are clear: the wealthiest 0.54 percent, about 40 million people, are responsible for 14 percent of lifestyle-related greenhouse gas emissions, while the bottom 50 percent of income earners, almost 4 billion people, only emit around 10 percent.

The world’s top 10 percent income earners are responsible for at least 25 percent and up to 43 percent of our environmental impact. Most people living in developed countries would fit into this category and while many of them may not feel very wealthy, they still have a disproportionately large and unsustainable resource footprint compared to the global average.

It is less clear, however, how to address the problems that come with affluence. Progressive mainstream policymakers talk about “greening consumption” or “sustainable growth” to “decouple” affluence from climate breakdown, biodiversity loss and other planetary-scale destruction.

Yet our research confirms that, in reality, there is no evidence that this decoupling is actually happening. While technological improvements have helped to reduce emissions and other environmental impacts, the worldwide growth in affluence has consistently outpaced these gains, driving all the impacts back up.

And it appears highly unlikely that this relationship will change in the future. Even the cleanest technologies have their limitations and still require specific resources to function, while efficiency savings often simply lead to more consumption.

If technology alone is not enough, it is therefore imperative to reduce the consumption of the affluent, resulting in sufficiency-oriented lifestyles: “better but less”. This is all easier said than done though, for there is a problem.

The super-affluent shape the world they live in

The increased material footprint (MF) and CO2 from fossil-fuels (CO2 FFI) bascially mirrors GDP growth. Detailed description of this Figure is in "Scientists’ warning on affluence". Top of page: photo by Exploringlife - own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45493945

The lockdown has seen a massive drop in consumption. But the resulting unprecedented dive in CO₂ and air pollutant emissions was merely incidental to the lockdown, not a deliberate part of it, and will not last.

So how can we reduce consumption as much as necessary in a socially-sustainable way, while still safeguarding human needs and social security? Here it turns out the main stumbling block is not technological limits or economics itself, but the economic imperative to grow the economy, spurred by overconsumption and the political power of the super-affluent.

Affluent, powerful people and their governments have a vested interest in deliberately promoting high consumption and hampering sufficiency-oriented lifestyles. Since consumption decisions by individuals are strongly influenced by information and by others, this can lock in high-consumption lifestyles.

“Positional consumption” is another key mechanism, where people increasingly consume status goods once their basic needs are satisfied. This creates a growth spiral, driven by the affluent, with everyone striving to be “superior” relative to their peers while the overall consumption level rises. What appears average or normal in a developed country then rapidly becomes a top contribution at the global level.

So, how can we get out of this dilemma?

We reviewed a variety of different approaches that may have the solution. They range from reformist to radical ideas, and include post-development, degrowth, eco-feminism, eco-socialism and eco-anarchism. All these approaches have in common that they focus on positive environmental and social outcomes and not on economic growth. Interestingly, there seems to be quite some strategic overlap between them, at least in the short term.

Most agree on the necessity to “prefigure” bottom-up as much as possible of the new, less affluent, economy in the old, while still demonstrating sufficiency oriented lifestyles to be desirable.

Grassroots initiatives such as Transition Initiatives and eco-villages can be examples of this, leading to cultural and consciousness change.

Eventually, however, far-reaching policy reforms are needed, including maximum and minimum incomes, eco-taxes, collective firm ownership and more. Examples of policies that start to incorporate some of these mechanisms are the Green New Deals in the US, UK and Europe or the New Zealand Wellbeing Budget 2019.

Social movements will play a crucial role in pushing for these reforms. They can challenge the notion that riches and economic growth are inherently good and bring forward “social tipping points”.

Ultimately, the goal is to establish economies and societies that protect the climate and ecosystems and enrich people with more wellbeing, health and happiness instead of more money.

This explainer was first published in The Conversation by Professors Thomas Wiedmann, UNSW, Julia Steinberger, University of Leeds and Professor Manfred Lenzen, University of Sydney.