Rethinking pest management to protect native species

Giving native animals an advantage over new arrivals

Australian native species might seem overrun by feral invaders, but Professor Peter Banks has an ingenious idea that could bring the odds back in their favour.

As COVID closed down New York’s restaurants and fast food joints, food waste quickly disappeared from gutters, dumpsters and garbage bins. Within days, there were stories of rat gangs fighting in alley ways for scraps. There were stories of rat cannibalism.

Though New York has Norway or brown rats, similar scenes possibly played out with Sydney’s black rats which have the rakish scientific name of Rattus rattus (brown rats, are Rattus norvegicus).

While rat populations are less dense here, the recent spike in rat-control callouts to suburban homes can probably be explained by people spending more time at home, post-COVID, and seeing the rats they’ve always lived near.

Arriving with the first Europeans, the black rat (Rattus rattus) became so plentiful so quickly, the new settlers thought they were native fauna. Where native habitat was destroyed, the black rats prospered.

An interested and informed observer of all this has been Professor Peter Banks (BSc ’92 PhD(Science) ’97). He leads the Behavioural Ecology and Conservation Lab in the School of Life and Environmental Sciences. Rats are one of his things. Though considering the bad-guy reputation of Rattus rattus, he offers a more nuanced insight.

“They’re not very good competitors. Normally, they’ll shy away from a fight,” he says.

Banks remembers as a youngster, standing in front of his high school and talking about conserving forests. An interest in science soon emerged; first physics and chemistry, then biology came into focus. His honour’s research was on the biology of native small mammals.

A key question for Banks, that frames much of his work, is this: why don’t native animals in their own environments actually have an advantage over new arrivals? The main answer is often habitat destruction but there’s more to it. One element is naivety.

“Naivety has many aspects but it can be as simple as a native not recognising an introduced animal as a predator,” says Banks, who travels Australia observing animal interactions in the wild. “It’s an element of animal behaviour that shapes outcomes. But with the right knowledge, it can be manipulated in favour of the natives.”

A brief history of Rattus in Australia

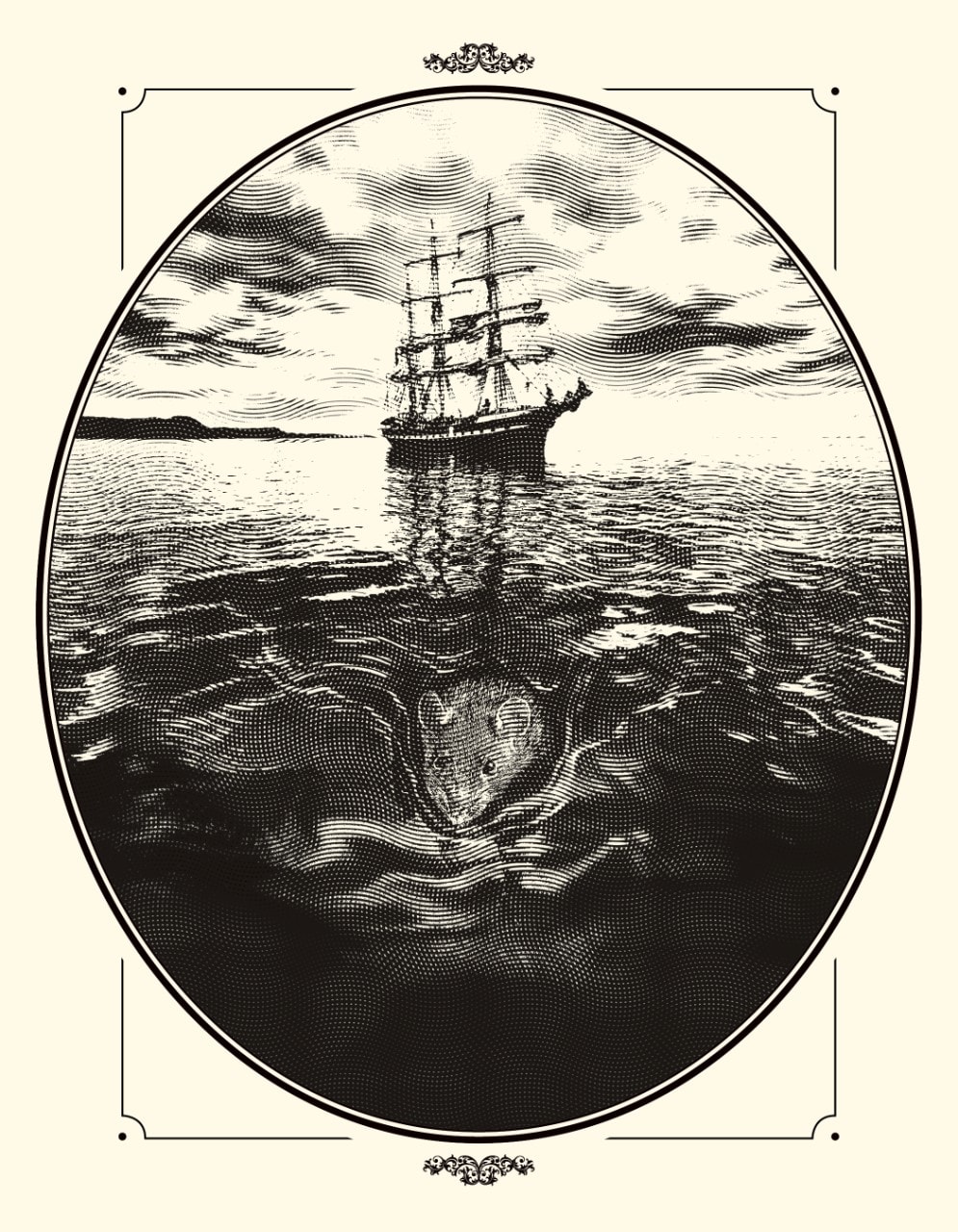

This is clearly demonstrated in the interaction of Australia’s feral rats and its native birds. The story starts with the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788.

Rather than documenting the decline of the natural world, Professor Peter Banks (above) wants his work to be a voice for plants and animals.

As the first European foot touched Australian ground, the foot of the first European black rat wasn’t far behind. In fact, they entrenched themselves so quickly, some settlers thought they were natives. Rats have since damaged agriculture, infested buildings and spread disease, bringing little of value to these shores, except perhaps the inspiration for that quintessentially Australian remark, flash as a rat with a gold tooth.

Those first rats soon realised they had family in their new home. Australia already had numerous species of local rodents, evolved from two previous rodent arrivals; one 4 million years ago (perhaps a single rat family clinging to a palm frond), the other 1 million years ago, both facilitated by land bridges created as oceans rose and fell.

Rodents have been in Australia for millions of years, but the European black rat arrived in Australia aboard ships in the later 18th century. Photo: iStock.

The key difference between most native Rattus and the 18th century arrivals was that the newly arrived black rats were good climbers. This meant the nests of Australian native birds were now up for pillaging by a new, egg-eating marauder. There haven’t been any definitive studies on what effect introduced rats have had on native bird populations so, as a scientist, Banks can’t commit.

That said, he does note that rat-populated urban areas have very few small, native birds. He has also tested the proposition.

“We put out a fake nest with a tiny amount of bird nesting odour,” he says. “Within a day, rats had found the nest and eaten the egg.”

I’ve done a lot of work in feral pest management, but to conserve some things the ideal would be to not necessarily kill other things.

The game-changer

A saving grace for native birds in the regions is that black rats tend to prefer disturbed landscapes near urban areas. As mentioned earlier, black rats also aren’t really up for a fight, “We did an experiment that showed if you remove the black rats and bring back the native rats, the black rats find it harder to get back in,” says Banks.

Though not yet verified, there is a strong scientific suspicion that egg-eating black rats have had a devastating effect on native bird populations. Photo: iStock.

With the insight into nesting odour and rat behaviour, came a perhaps game-changing idea: what if you sprayed bird nesting odour all over an area where birds like to nest so rats aren’t able to actually pinpoint the nests at all?

“We tested that idea round Sydney, then took it to New Zealand, working with people from the Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research facility. The paper hasn’t been published yet, but the method saw a doubling of breeding success for endangered shore birds in the areas where it wasn’t possible to actually remove the predators.

“I didn’t believe it really,” says Banks still excited by the idea. “But it was there in the results. It was amazing.”

Disruptive thinking and minimising eradication

In effect, this is a form of disruptive thinking. Identify how invading species find their food or prey, know where they like to take shelter, understand why the native species don’t cope, then come up with ideas to disrupt all that and tilt the game back in favour of the natives. This game plan plays to one of Banks’ key goals.

“I’ve done a lot of work in feral pest management,” Banks says. “But to conserve some things the ideal would be to not necessarily kill other things.”

Allowing that the phrase ‘eradication program’ is often used in pest control circles, a reticence to eradicate seems perhaps anti-intuitive. Certainly, there is a long list of animals most Australians would happily see pushing up the native daisies: cane toads, feral pigs, feral carp.

Things get a bit more emotional with the cute ones, like the brumbies of Kosciusko. Sure, they’re a numerous and destructive pest in a fragile environment, but no-one really wants to see them being shot from helicopters.

The shy, native bandicoot is often mistaken for a rat. Pro-tip: bandicoots have shorter tails than rats, and a much longer, pointier nose. Photo: iStock.

Return of the bandicoot

“We haven’t killed anything in the New Zealand bird experiment at all, but we reduced the impact of the invading species so the native species could return. It’s understanding the ecology that makes that possible. It can be applied in other places.”

Places like Sydney itself. In a reverse of usual outcomes, one native animal has made something of a comeback; the bandicoot, which is a small marsupial sometimes mistaken for a rat, that often becomes dinner for foxes and cats.

Banks has had a long-time interest in helping bandicoots hang on and he’s worked with local land managers at Sydney’s North Head to nurture the natural population and protect it.

“Again, it’s about understanding biology so you can look after bandicoots better,” says Banks. “National Parks has had really encouraging success with it. The numbers have grown, the population is stable and slowly moving back into the suburbs. It’s a good news story.”

PROTECT OUR ANIMALS AND BIRDS

To learn more about this story or to support the vital work of Professor Banks, please contact Kate Parsons. Phone: +61 2 8627 4490. Email: development.fund@sydney.edu.au.

Written by George Dodd for Sydney Alumni Magazine.