How the gaming industry justifies in-game gambling

Dr Mark Johnson.

As at last year, the global gaming industry was valued at USD$162 billion (AUD$213 bn), with at least $20 billion (AUD$26 bn) of this revenue sourced from in-game gambling mechanisms. Loot boxes – virtual lucky dips that players can purchase with real-life money – have become prolific: almost 60 per cent of games in the Google Play store in 2020 contained them.

A literature review published in the Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds, led by a University of Sydney researcher, identifies how the gaming industry defends in-game gambling mechanisms.

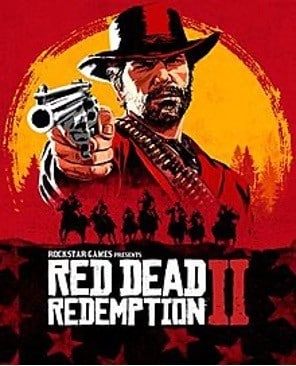

First, it cites the rising costs of game making. For example, in 1996, it cost around $1.7m to make a major blockbuster game, like Crash Bandicoot. By contrast, one of the biggest games of 2020, Red Dead Redemption 2, cost more than $250 million. Despite rising profits from games, the games sector uses such figures to defend gambling-equivalent monetisation methods.

Second, the games industry states in-game gambling is necessary for profit-making, due to greater competition in the gaming marketplace. “Many digital platforms are flooded with low-quality games. Companies are going bust or being subsumed into others,” said lead researcher, Lecturer in Digital Cultures Dr Mark Johnson. “Consequently, all games companies and game developers except the very largest actors are feeling a growing pressure to make their games stand out.”

Dr Johnson, from the School of Literature, Art and Media, also found a third, ‘most significant’ reason for the rise of in-game gambling: game development companies are increasingly profit-oriented. Over the past few decades, a handful of companies have risen to the pinnacle of the gaming industry, with resources comparable to major film and music studios.

Although we hesitate to use an emotionally loaded term like ‘corporate greed’, the evidence suggests such a framing is not far from the truth

One of the biggest games of 2020, Red Dead Redemption 2, cost more than $250 million to produce. Credit: Rockstar Games via Wikipedia.

“Consequently, a major shift is taking place in the games industry, from creating a cultural product and trying to make enough money to be sustainable, to loading games with monetisation methods,” he said. “Although we hesitate to use an emotionally loaded term like ‘corporate greed’, the evidence suggests such a framing is not far from the truth.”

"The gaming industry is now constantly finding new ways to extract money from players. Loot boxes, which are essentially gambling devices, are highly effective, as they kick in after players have been recruited through the allure of free play.”

This is known as a ‘freemium’ model, which originated with casinos offering people free food or drinks in exchange for plays on the roulette or baccarat table. In gaming, the model relies on driving goal-oriented automated behaviours that develop through repeated (paid) consumption of coins, keys, passes, and other items – won in loot boxes – that can remove barriers to in-game progression. The success of Epic Games’ Fortnite, for example, has been attributed to its freemium model.

Dr Johnson continued: “The pervasiveness of loot boxes is inevitably leading to changes in the types of games that are being created, how players experience games, and public opinion on digital gaming.

“This industry shift brings newfound urgency to debates around gaming regulation and stresses the need for a broader focus – beyond effects on individual players.”

Hero image: Alexander Andrews via Unsplash.