Sydney archaeologist helps reveal oldest human burial in Africa

A new study published in Nature by an international team of researchers details the earliest modern human burial in Africa. The remains of a 2.5 to 3 year-old child were found in a flexed position, deliberately buried in a shallow grave directly under the sheltered overhang of the cave. The burial at Panga ya Saidi in Kenya joins increasing evidence of early complex social behaviours in Homo sapiens.

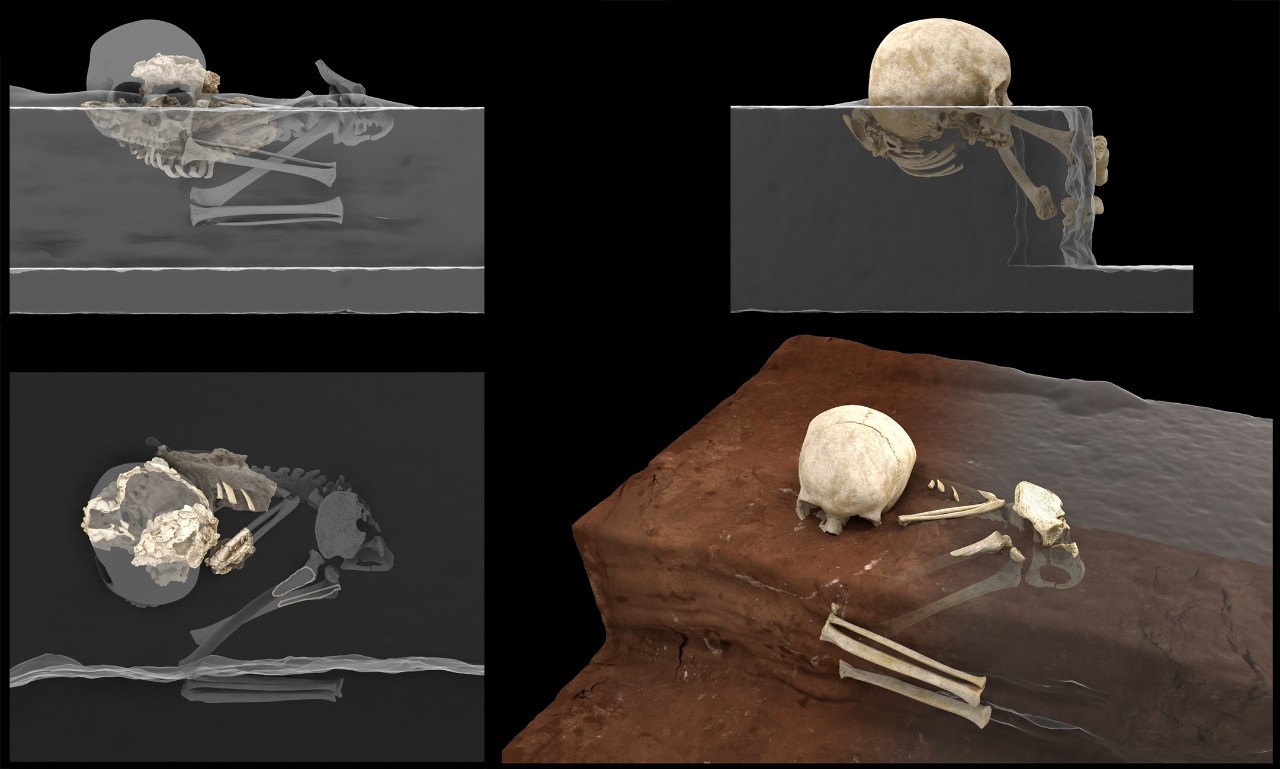

Virtual reconstruction of the Panga ya Saidi hominin remains at the site (left) and ideal reconstruction of the child’s original position at the moment of finding (right). Photo credit: Jorge González/Elena Santos

University of Sydney archaeologist Dr Patrick Faulkner was one of 36 global researchers who contributed to the discovery. His role was analysing the shell fragments of a giant African snail shell found in the burial site.

“This is a very exciting discovery, it’s something we haven’t seen in Africa before. It is really important on a global level, filling in a critical gap in our understanding of the development of complex human behaviours,” says Dr Faulkner, who is a senior lecturer in the Department of Archaeology in the School of Philosophical and Historical Enquiry.

Though the Panga ya Saidi discovery represents the earliest evidence of intentional burial in Africa, burials of Neanderthals and modern humans in Eurasia range back as far as 120,000 years. The reasons for the lack of early burials in Africa remain elusive, perhaps owing to differences in mortuary practices or the lack of field work in large portions of the African continent.

Early evidence of burials in Africa are scarce and often ambiguous. Little is known about the origin and development of mortuary practices in Africa. A child buried at the mouth of the Panga ya Saidi cave site 78,000 years ago is changing that, revealing how Middle Stone Age populations interacted with the dead.

View of the cave site of Panga ya Saidi. Note trench excavation where burial was discovered. Photo: Mohammad Javad Shoaee

Panga ya Saidi has been an important site for human origins research since excavations began in 2010 as part of a long-term partnership between archaeologists from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (Germany) and the National Museums of Kenya (Nairobi).

Portions of the child’s bones were first found during excavations at Panga ya Saidi in 2013, but it wasn’t until 2017 that the small pit containing the bones was fully exposed. About three metres below the current cave floor, the shallow, circular pit contained tightly clustered and highly decomposed bones, requiring stabilisation and plastering in the field.

“At this point, we weren’t sure what we had found. The bones were just too delicate to study in the field,” says Dr Emmanuel Ndiema of the National Museums of Kenya. “So we had a find that we were pretty excited about - but it would be a while before we understood its importance.”

Human remains in the lab

Virtual ideal reconstruction of Mtoto’s position in the burial pit. Photo: Jorge González/Elena Santos

Once plastered, the cast remains were brought to the laboratories of the National Research Center on Human Evolution (CENIEH) in Burgos, Spain, for further excavation, specialised treatment and analysis. Two teeth were identified as belonging to a 2.5- to 3-year-old human child, who was later nicknamed Mtoto, which means child in Swahili.

Microscopic analysis of the bones and surrounding soil confirmed that the body was rapidly covered after burial and that decomposition took place in the pit. In other words, Mtoto was intentionally buried shortly after death.

“The position and collapse of the head in the pit suggested that a perishable support may have been present, such as a pillow, indicating that the community may have undertaken some form of funerary rite,” said Professor María Martinón-Torres, director at CENIEH.

Sydney archaeologist shell findings

Dr Patrick Faulkner holding a specimen of a giant African land snail shell.

Dr Patrick Faulkner contributed to the discovery by analysing a collection of land snail shell fragments from the burial site, working with Francesco d’Errico and Solange Rigaud (both of the Université Bordeaux) who undertook the detailed microscopic analyses. The shell was from a species of giant African land snail found near the bones, as well as shell from the sediments beneath the burial.

“I’ve studied marine and land snail shells from coastal African archaeological sites in the past. That work really focused on understanding how these molluscs contributed to the diet and use of landscapes around each site. In this case, we needed to focus on how and why these land snail fragments connected to the burial, whether they were modified by humans and intentionally buried with Mtoto, or found their way in naturally,” Dr Faulkner said.

Giant African land snails

African land snails reach lengths of 20cm or more depending on the species. They exist across much of Africa south of the Sahara, although the ones Dr Faulkner has studied occur naturally in the hinterland forests, coasts and islands of East Africa (and are highly invasive pests in other parts of the world). Historically, the shell was used as a container due to its size, or modified for use as a tool (like scrapers) or implement (like spoons).

Giant African land snails can grow up to 20cms. These are two specimens from different species with smaller marine shells to show their size.

“Our findings suggest a number of different processes related to the way early humans were using these snails. There is evidence of heating on some of the fragments from the sediments beneath the burial, which would indicate that people were cooking and eating the snails (a practice that continues in Africa to this day),” Dr Faulkner said.

"We also see modification to one specimen that was located very close to the child’s skeleton, with deep incisions to the shell that are not likely to have occurred naturally," he said. "It’s difficult to interpret this kind of evidence from a single specimen, so we can’t clearly point to ritual, ceremony, or some kind of decoration, but it does suggest human modification in some way.”

"There was also a difference in the extent of breakage found between the five specimens associated with the burial and the collection from the underlying layer. Taken together, this information adds to the interpretation of this being an intentional burial,” says Dr Faulkner.

Shell studies

“Not many people realise archaeologists study shells in this way,” Dr Faulkner said. "Rather than being small and insignificant, ancient shells have the potential to tell us a great deal about settlement, economic structures and local environmental conditions. In this case, it provided one piece of the puzzle. Panga ya Saidi is a once-in-a-career site and it has been an honour to work as part of this global research team.”

Dr Faulkner’s work was undertaken in Australia, at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany, and the National Museum of Kenya in Nairobi.

Mtoto the sleeping child

Watch an 8 minute documentary

Ancient human burials

Luminescence dating securely places Mtoto’s burial at 78,000 years ago, making it the oldest known human burial in Africa. Later burials from Africa’s Stone Age also include young people – perhaps signalling special treatment of the bodies of children in this ancient period.

The human remains were found in archaeological levels with stone tools belonging to the African Middle Stone Age, a distinct type of technology that has been argued to be linked to more than one hominin species.

“The association between this child’s burial and Middle Stone Age tools has played a critical role in demonstrating that Homo sapiens was, without doubt, a definite manufacturer of these distinctive tool industries, as opposed to other hominin species,” notes Dr Ndiema.

The Panga ya Saidi burial shows that inhumation of the dead is a cultural practice shared by Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, notes Professor Michael Petraglia of the Max Planck Institute in Jena. “This find opens up questions about the origin and evolution of mortuary practices between two closely related human species, and the degree to which our behaviours and emotions differ from one another.”

Partnerships: The excavations at Panga ya Saidi are jointly led by the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (Jena, Germany) and the National Museums of Kenya (NMK). The conservation and analysis of the Panga ya Saidi skeletal remains were led by CENIEH (Burgos, Spain). The international consortium of scientists includes members primarily from organisations and universities in Kenya, Germany, Spain, France, Australia, Canada, South Africa, the UK, and the USA.

Declaration: Dr Faulkner’s research has been supported by the Tom Austen Brown Endowment, the School of Philosophical and Historical Enquiry, Research Support Grants, and the Max Planck Society.