Firefighting chemicals found in sea lion and fur seal pups

A chemical that the governmentof New South Wales, a state within Austraia, recently partially banned in firefighting has been found in the pups of endangered Australian sea lions and in Australian fur seals.

The finding represents another possible blow to Australian sea lions’ survival. Hookworm and tuberculosis already threaten their small and diminishing population, which has fallen by more than 60 percent over four decades.

The new research, part of a long-term health study of seals and sea lions in Australia, identified the chemicals in animals at multiple colonies in the Australian states of Victoria and South Australia from 2017 to 2020.

As well as in pups, the chemicals (Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances – ‘PFAS’) were detected in juvenile animals and in an adult male. There was also evidence of transfer of the chemicals from mothers to newborns.

PFAS have been reported to cause cancer, reproductive and developmental defects, endocrine disruption and can compromise immune systems.

Exposure can occur through many sources including through contaminated air, soil and water, and common household products containing PFAS.

In addition to being used in firefighting foam, they are frequently found in stain repellents, polishes, paints and coatings.

The researchers believe the seals and sea lions ingested the chemicals through their fish, crustacean, octopus and squid diets.

Despite South Australia banning the use of PFAS-containing firefighting foams in 2018, these chemicals persist and don’t easily degrade in the environment.

They have not been banned in Victoria.

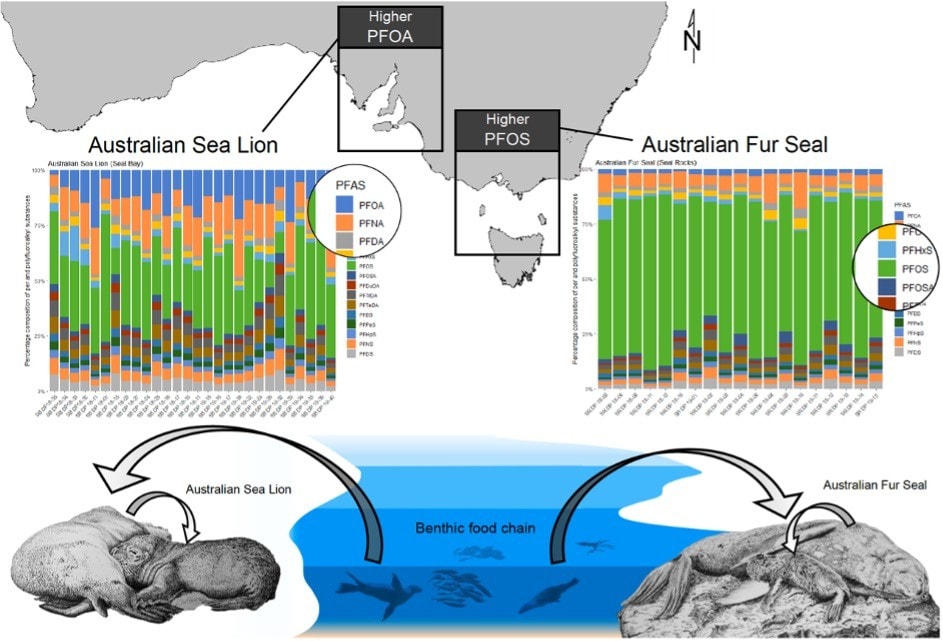

Greater levels of PFOA (perfluorooctanioc acid) were detected in the endangered Australian sea lion while Australian fur seals had greater PFOS (perfluorooctane sulfonate) concentrations. PFOA and PFOS are types of PFAS (Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) – chemicals used in firefighting foams. Credit: Taylor et al.

High chemical concentrations

Published in Science of the Total Environment, this is the first study to report concentrations of PFAS in seals and sea lions in Australia.

PFAS concentrations in some animals were comparable to those in marine mammals in the northern hemisphere including southern sea otters and harbour seals.

Particularly high concentrations of the chemicals were found in newborns – transferred during gestation or via their mothers’ milk.

“This is particularly concerning, given the importance of the developing immune system in neonatal animals,” said research co-lead, Dr Rachael Gray from the Sydney School of Veterinary Science.

“While it was not possible to examine the direct impacts of PFAS on the health of individual animals, the results are crucial for ongoing monitoring.

"With the Australian sea lion now listed as endangered, and Australian fur seals suffering colony-specific population declines, it is critical that we understand all threats to these species, including the role of human-made chemicals, if we are to implement effective conservation management.”

Credit: Louise Cooper.

Food chain implications

The findings have implications for the entire food chain of which the pups are part, including adult seals and sea lions, fish and even humans.

“Because PFAS last a long time, they can become concentrated inside the tissues of living things.," Dr Gray said.

"This increases the potential for exposure to other animals in the food chain, particularly top marine mammal predators like seals and sea lions.

“There is also the potential for humans to be exposed to PFAS by eating contaminated seafood, drinking contaminated water, or even through eating food grown in contaminated soil.

“So, not only do PFAS threaten native endangered species like the Australian sea lion – they could pose a risk to humans too.”

Credit: Louise Cooper.

Methodology

A collaboration between the University of Sydney, National Measurement Institute and Phillip Island Nature Parks, the research, chiefly undertaken by University of Sydney PhD student Shannon Taylor, was partly conducted on site at the animals’ colonies, with later testing of animal livers at the National Measurement Institute in Sydney.

The livers were analysed using a complex method called high-performance liquid chromatograph/triple quadrupole mass spectrometry.

At its most basic, this method ionises a molecular compound and then separates and identifies the components based on their mass-to-charge ratio.

In this way, specific chemicals and their abundance can be measured.

Declaration: Funding for this research was through the Ecological Society of Australia via a Holsworth Grant to PhD student and lead author Shannon Taylor.

The Hermon Slade Foundation provided funding for field support for these ongoing investigations and Sydney School of Veterinary Science bequests also provided financial support.

Staff at Seal Bay Conservation Park, Department for Environment and Water, South Australia and Phillip Island Nature Parks provided logistical support.

Credit: Louise Cooper.

The endangered Australian sea lion

Dr Rachael Gray and her team of scientists have been conducting world-class research in South Australia in order to save the endangered sea lion.

The Australian sea lion is the only pinniped species endemic to Australian waters, ranging from the Houtman Abrolhos islands off the west coast of Western Australia to the Pages Islands in South Australia.

The species is endangered, with a decreasing population trend (International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List) from a low baseline attributed to 19th century commercial sealing.

The small population size increases the species’ risk of catastrophic disease impact, as seen in the New Zealand sea lion where neonatal septicaemia and meningitis contributed to 58 percent of pup deaths between 2006 and 2010.

Hookworm infection provides an existing disease pressure for the Australian sea lion.

Further, recovery from a significant disease impact would be limited by the species’ low reproductive rate.

The majority (82 percent) of pup births occur in South Australia where there is dependence on just eight large breeding colonies, including Seal Bay, Kangaroo Island.

Hero image: A sea lion pup on Kangaroo Island, SA. Credit: Louise Cooper.