Bet on technology or limit growth? Climate modelling shows 'degrowth' less technologically risky

A comprehensive comparison of 'degrowth' with established pathways to limit climate change highlights the risk of over-reliance on technology to support economic growth, which is assumed in established climate modelling.

The first comprehensive comparison of ‘degrowth’ scenarios with established pathways to limit climate change highlights the risk of over-reliance on carbon dioxide removal, renewable energy and energy efficiency to support continued global growth - the approaches assumed in established global climate modelling.

Degrowth is defined as an equitable, democratic reduction in energy and material use while maintaining wellbeing. A decline in GDP is accepted as a likely outcome of this transition. It focuses on the global North because of historically high levels of energy and material use in affluent nations, thereby enabling a just transition mindful of poverty especially in low-income nations.

The new modelling by the University of Sydney and ETH Zürich includes high growth/technological change and scenarios summarised by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as a comparison to degrowth pathways. It shows that by combining far-reaching social change focused on sufficiency as well as technological improvements, net-zero carbon emissions can be more easily achieved technologically.

The findings were published today in the leading journal Nature Communications.

It appears to be a significant oversight that degrowth is not even considered in the conventional climate modelling community.

Currently the IPCC’s and established modelling community’s integrated assessment models (IAM), do not consider degrowth scenarios where reduced production and consumption in the global North is combined with maintaining wellbeing and achieving climate goals. In contrast, established scenarios rely on combinations of unprecedented carbon dioxide removal from the atmosphere and other far-reaching technological changes.

The results show the international targets of capping global warming to 1.5⁰C-2⁰C above pre-Industrial levels can be achieved more easily in key dimensions, for example:

- Degrowth in the global North/high-income countries results in 0.5 percent annual decline of global GDP. However, a substantially increased uptake of renewable energy coupled with negative emissions remains necessary, albeit significantly less than in established pathways.

- Capping warming to the upper limit of 2⁰C can be achieved with 0 percent growth, while being consistent with low levels of carbon dioxide removal (i.e. from tree planting) and increases in renewable energy as well as energy efficiency.

The researchers modelled 18 degrowth scenarios as alternatives to technology-driven methods of reducing carbon dioxide. Credit: Jacqueline Godany via Unsplash.

Lead author, Mr Lorenz Keyßer, from ETH Zürich whose Master’s thesis is on degrowth, carried out the research in Australia under supervision of global leader in carbon footprinting Professor Manfred Lenzen, from the University of Sydney’s centre for Integrated Sustainability Analysis (ISA) in the School of Physics.

Mr Keyßer said he was surprised by the clarity of the results: “Our simple model shows degrowth pathways have clear advantages in many of the central categories; it appears to be a significant oversight that degrowth is not even considered in the conventional climate modelling community.

“The over-reliance on unprecedented carbon dioxide removal and energy efficiency gains means we risk catastrophic climate change if one of the assumptions does not materialise; additionally, carbon dioxide removal shows high potential for severe side-effects, for instance for biodiversity and food security, if done using biomass. It thus remains a risky bet.

“Our study also analysed the other key assumption upon which the modelling of the IPCC and others is based: continued growth of global production and consumption.”

Professor Lenzen says the idea of removing several hundred gigatonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, assumed in the IPCC scenarios to meet the 1.5⁰C target, faces substantial uncertainty.

The senior author Professor Lenzen says the technological transformation is particularly extraordinary given the scale of carbon dioxide removal assumed in the IPCC Special Report, Global warming of 1.5⁰C, of between 100-1000 billion tonnes (mostly over 600 GtCO2) by 2100; in large part through bioenergy to carbon capture and storage (BECCS) as well as through afforestation and reforestation (AR).

“Deployment of controversial ‘negative emissions’ future technologies to try to remove several hundred gigatonnes [hundreds of billion tonnes] of carbon dioxide assumed in the IPCC scenarios to meet the 1.5⁰C target faces substantial uncertainty,” Professor Lenzen says.

“Carbon dioxide removal (including carbon capture and storage or CCS) is in its infancy and has never been deployed at scale.”

What degrowth might look like

The new modelling was undertaken pre-COVID-19 but the degrowth pathways are based on a fraction of global GDP shrinkage of some 4.2 percent experienced in the first six months of the pandemic. Degrowth also focuses on structural social change to make wellbeing independent from economic growth.

“We can still satisfy peoples’ needs, maintain employment and reduce inequality with degrowth, which is what distinguishes this pathway from recession,” Mr Keyßer says.

“However, a just, democratic and orderly degrowth transition would involve reducing the gap between the haves and have-nots, with more equitable distribution from affluent nations to nations where human needs are still unmet – something that is yet to be fully explored.”

A “degrowth” society could include:

- A shorter working week, resulting in reduced unemployment alongside increasing productivity and stable economic output.

- Universal basic services independent of income, for necessities i.e. food, health care, transport.

- Limit maximum income and wealth, enabling a universal basic income to be increased and reducing inequality, rather than increasing inequality as is the current global trend.

Among the 1.5°C degrowth pathways explored in the new research, the Decent Living Energy (DLE) scenario – providing decent living globally with minimum energy – is closest to historical trends for renewable energy and negligible ‘negative emissions’. Mr Keyßer says the International Energy Agency projections for renewables growth to 2050 based on past trends are roughly equivalent to the DLE pathway modelled.

“That non-fossil energy sources could meet ‘decent living energy’ requirements while achieving 1.5°C – under conditions close to business-as-usual – is highly significant," Mr Keyßer says.

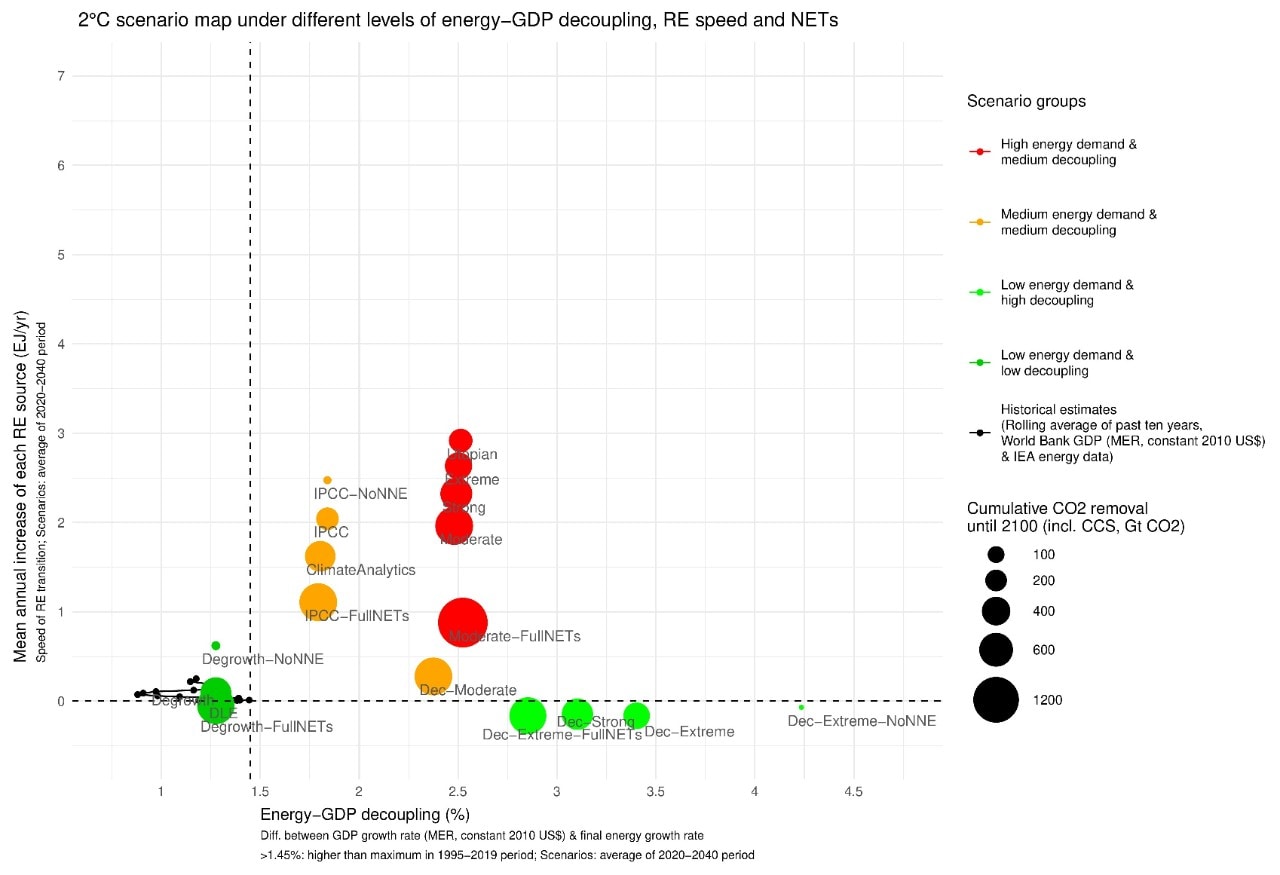

Modelling highlights the reliance on carbon dioxide removal or CCS (size of circle) of various growth pathways to limit global warming, compared to ’degrowth’, which is on track to achieve climate targets under historical trends, i.e. minimal technological changes (small black dots near zero). Credit: Lorenz Keyßer

Modelling climate pathways

For the study, a simplified quantitative representation of the relationship between fuel, energy and emissions was used as a first step to overcome what the authors believe is an absence of comprehensive modelling of degrowth scenarios in mainstream circles like the IAM community and IPCC. The model is accessible in open access via the paper online.

A total of 18 scenarios were modelled:

- Degrowth and ‘decent living energy (DLE)’, looking at low energy use and energy efficiency (GDP decoupling).

- Medium energy use/decoupling, including approximated IPCC scenarios.

- High energy use/decoupling (strong-to-extreme technology pathways/energy efficiency driving separation between economic growth and emissions).

Mr Keyßer says: “This study demonstrates the viability of degrowth in minimising several key feasibility risks associated with technology-driven pathways, so it represents an important first step in exploring degrowth climate scenarios.”

Professor Lenzen concludes: “A precautionary approach would suggest degrowth should be considered, and debated, at least as seriously as risky technology-driven pathways upon which the conventional climate policies have relied.”

Declaration: This work was supported by the Australian Research Council through its Discovery Projects DP0985522 and DP130101293; Linkage Infrastructure, Equipment and Facilities Grant LE160100066; and the National eResearch Collaboration Tools and Resources project (NeCTAR) through its Industrial Ecology Virtual Laboratory (IELab).

Hero image: Mika Baumeister via Unsplash.