With research, communities should lead and academics follow

Dr James Flexner (centre) undertaking community-led research in Vanuatu. Credit: Dr Flexner.

There is an upside to arriving in Vanuatu with just a GPS, a notepad, and a few basic supplies. University of Sydney archaeologist Dr James Flexner learnt this when instead of delving into technical work, he met with local chiefs and elders who explained the local landscape of Williams Bay. “The result was ultimately probably richer and more interesting than if I had simply followed the orthodox approach to archaeological survey,” he said.

Dr Flexner’s observations form part of a forthcoming open-access volume he co-edited, Community-Led Research: Walking New Pathways Together. In collaboration with University of Sydney colleagues Associate Professor Lynette Riley (Indigenous education) and Dr Victoria Rawlings (youth gender and sexuality), he collates diverse perspectives on this relatively novel research method.

What is community-led research?

Traditional research on a community involves researchers arriving, announcing their intentions, and leaving once they have obtained desired results. Think, colonial-era archaeologists in Egypt, digging in the depths of pyramids and then shipping collected treasures back to Europe. Or, even in modern times, Indigenous people being studied with no apparent benefit or even point to the work done to and at them. The book outlines how community-led research flips this process on its head. It invites communities to identify the research questions they would like investigated and to shape research design, so they can steer research that might ultimately inform policies that affect them.

Dr James Flexner

Trials and triumphs

But is it not without hurdles. For example, “one of the ongoing problems in attempting to do community-led work in Vanuatu is the very real differences in the level of wealth between ‘there’ [Vanuatu] and ‘here’ [Australia],” Dr Flexner said. Though his research, funded by the Australian government, allowed him to hire locals as assistants, there was never enough money to go round. The power imbalance, he says, is clear and insurmountable, and can hamper work and therefore outcomes.

Book co-editor Dr Victoria Rawlings also had a remarkable experience when, together with academic colleague Professor Elizabeth McDermott from the University of Lancaster, she co-designed research on self-harm and suicide (including attempts) with queer young people who had personally experienced some of these phenomena.

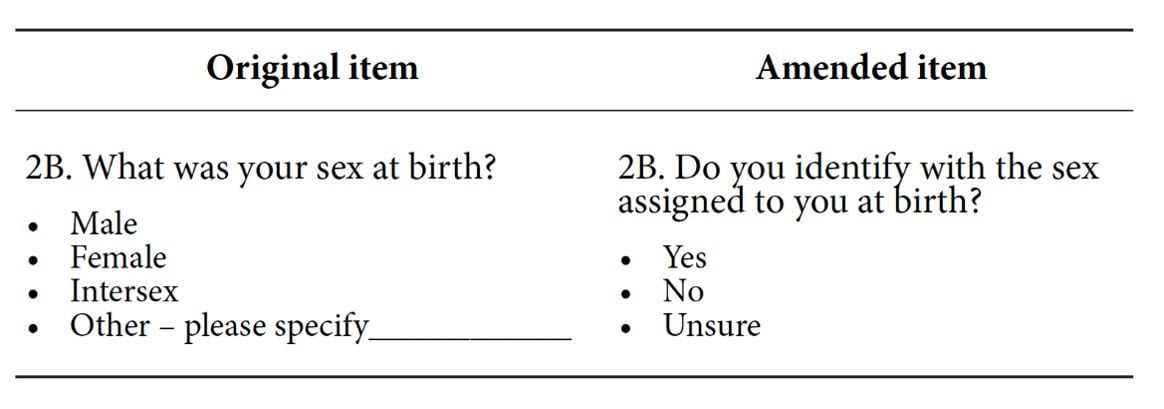

This consultation led to significant changes in the survey instrument being used in the study, with 14 of the 49 questions being altered. “Crucially, the young people’s feedback allowed us to alter and improve questions about gender identity and sexuality – questions that are notoriously difficult to design,” Dr Rawlings said. For example, one of the youth consultants, Dylan, who identified as transgender, suggested that the original below question could cause trans participants distress when they were asked to identify their birth sex, so it was changed.

Dr Victoria Rawlings and her study co-author changed survey questions after consulting with the community with whom they co-conducted their research.

Dr Rawlings believes that this consultative survey design, as well as the young people’s willingness to share the survey with their networks, contributed to the survey’s very low dropout rate (only 5.5 percent) and the large number of people who completed the survey (789, where just 400 would have made the sample statistically significant). She concludes that “community-led research produces better quality research, a better, more fulfilling experience for participants and more reliable research outcomes.”

Benefit communities, not researchers

The editors state that community-led research has not been ‘achieved’ – it is a work-in-progress. Its ultimate aims will only be fulfilled when communities lead, and researchers follow.

This is particularly pertinent to Indigenous communities, co-editor Associate Professor Riley says. “There is no argument that since the arrival of the British on the shores of what is now known as Australia, the First Nations people have been affected in ways that have at the least traumatised and irrevocably changed their lives; culturally, politically, legally and socially.

“It is also very clear that this is in part due to the impact of research undertaken since colonisation that was focused and in turn used in policies aimed at controlling Indigenous lives.”

Warren Roberts, a Thunghutti and Bundjalung man and community worker, says effective community-led research takes patience, listening, understanding and commitment. Credit: University of Sydney.

More recently, Associate Professor Riley says Indigenous Australians are often asked for their input when the government and others have run out of ideas. “It’s an attitude of, ‘Oh well, we don’t know what to do, what do you recommend?’ – but still with no guarantee of taking up those ideas,” she said.

This issue is addressed by the editors, who ask: “what would the research environment be like if, rather than researchers coming up with ideas and then trying to work with communities to study them, the community was given the initiative to tell researchers what they want?”

About the book

Community-Led Research: Walking New Pathways Together is published today (1 July 2021) by Sydney University Press.

Hero image: Deborah Warr, honorary Associate Professor at the University of Melbourne and Charles Sturt University, in discussion with Kelly Goldsworthy, a Barkindji/Ngiyaampaa woman and a researcher at Charles Sturt University. Credit: University of Sydney.