Most detailed map of brain’s memory hub finds connectivity puzzle

“We were surprised to find fewer connections between the hippocampus and frontal cortical areas, and more connections with early visual processing areas than we expected to see,” said Dr Marshall Dalton, a Research Fellow in the School of Psychology at the University of Sydney. “Although, this makes sense considering the hippocampus plays an important role not only in memory but also imagination and our ability to construct mental images in our mind’s eye.”

The study was published in the journal eLife.

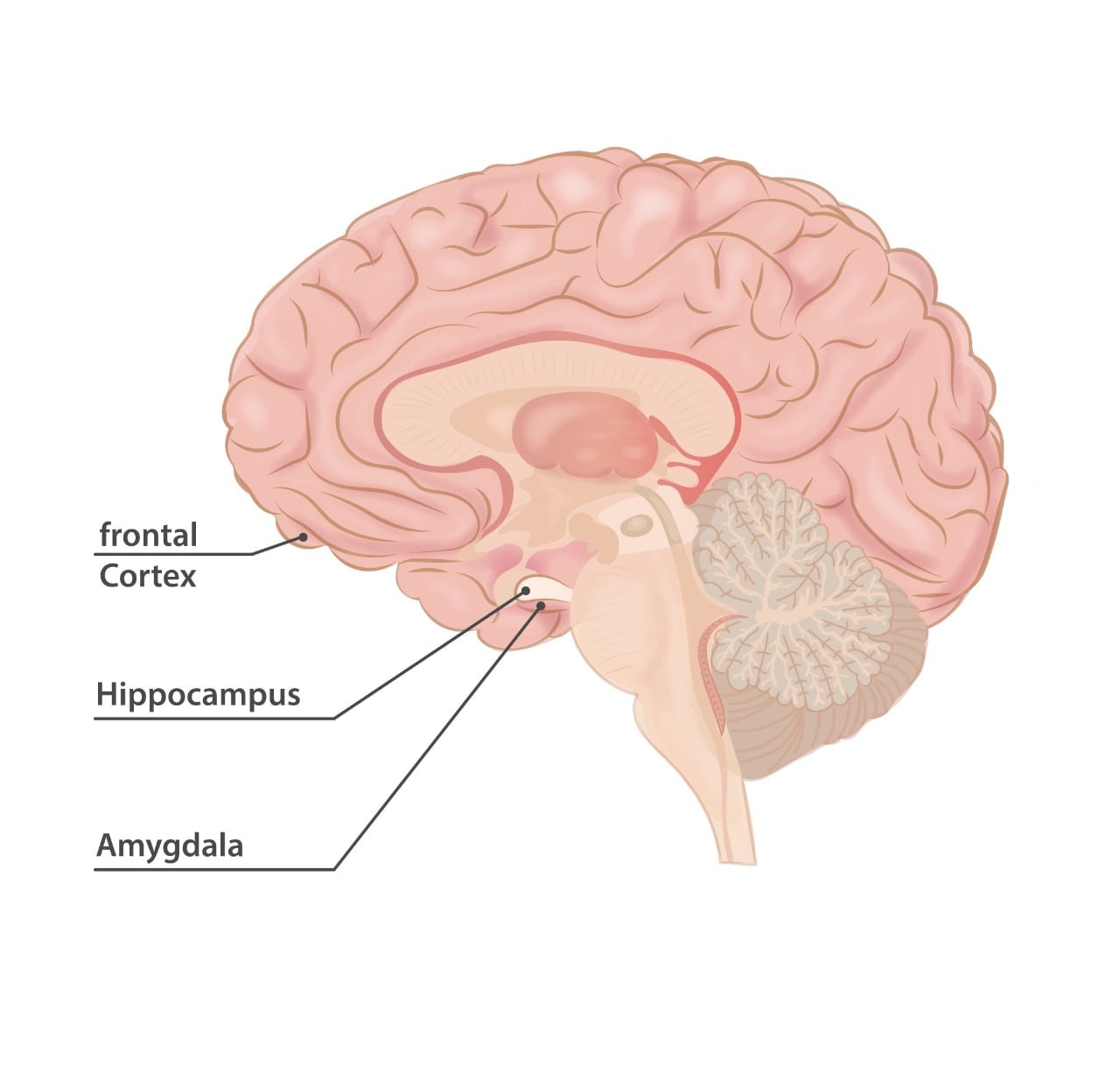

The hippocampus is a complex structure that resembles a seahorse and is tucked deep within the brain. As a vital component of the brain, it is important for memory formation and plays a key role in the transfer of memories from short-term to long-term storage. But it also plays a part in navigation, imagining fictitious or future experiences, creating mental imagery of scenes in the mind’s eye, and even in visual perception and decision making.

To generate their map, the team – led by Dr Dalton and including Dr Arkiev D’Souza, Dr Jinglei Lv and Professor Fernando Calamante from the University of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre – relied on MRI scans from a neuroimaging database created for the Human Connectome Project (HCP), a research consortium led by the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

They processed the existing HCP data using tailored techniques that they developed. This allowed them to follow the connections from all corners of the brain to their termination points in the hippocampus – something that had never been accomplished before in the human brain.

Most detailed map to date

png.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/cq5dam.web.1280.1280.jpeg)

Graphic showing the Hippocampus mapping process. Credit: Marshall Dalton

“What we’ve done is take a much more detailed look at the white matter pathways, which are essentially the highways of communication between different areas of the brain,” said Dr Dalton. “And we developed a new approach that allowed us to map how the hippocampus connects with the cortical mantle, the outer layer of the brain, but in a very detailed way.

“What we’ve created is a highly detailed map of white matter pathways connecting the hippocampus with the rest of the brain. It’s essentially a roadmap of brain regions that directly connect with the hippocampus and support its important role in memory formation.”

Technical limitations inherent to previous MRI investigations of the human hippocampus meant it was only possible to visualise its connections in very broad terms. “But we have now developed a tailored method that allows us to confirm where within the hippocampus different cortical areas are connecting. And that hasn’t been done before in a living human brain,” said Dr Dalton.

Unexpected results

Cross section of the human brain showing the hippocampus

The team was delighted their results largely aligned with data from previous studies overseas over the past few decades, which had relied on post-mortem studies of primate brains. However, the University of Sydney team found that the number of connections between the hippocampus and some brain areas was either much lower (in the case of frontal cortical areas) or higher (in the case of visual processing areas) than expected.

This could indicate that although some pathways were conserved as humans evolved, human brains may also have developed unique patterns of connectivity different from other primates. Further research is needed to tease this apart in more detail.

These differences in connectivity may just be a limitation of the MRI technique – or it could be real. They may, for example, help explain why some of our primate cousins – especially chimpanzees – are better at some memory tasks than humans, especially those relying on short-term memory. Chimpanzees have bested humans at cognitive tasks involving a form of mathematics known as game theory, which relies on short-term memory, pattern recognition and rapid visual assessment.

“Although we have achieved this high-resolution mapping of the human hippocampus, the tract tracing method conducted on non-human primates – which can see down to the cellular level – is able to see more connections than can be discerned with an MRI,” mused Dr Dalton.

“Or it could be that the human hippocampus really does have a smaller number of connections with frontal areas than we expect, and greater connectivity with visual areas of the brain. As the neocortex expanded, perhaps humans evolved different patterns of connectivity to facilitate human-specific memory and visualisation functions which, in turn, may underpin human creativity.

“It’s a bit of a puzzle – we just don’t know. But we love puzzles and will keep investigating.”