Octopuses witnessed hurling silt, shells and algae

Both sexes throw, but females do it more often

Professor Peter Godfrey-Smith from the Faculty of Science reveals why octopuses display this unique physiological trait, which he observed through his research.

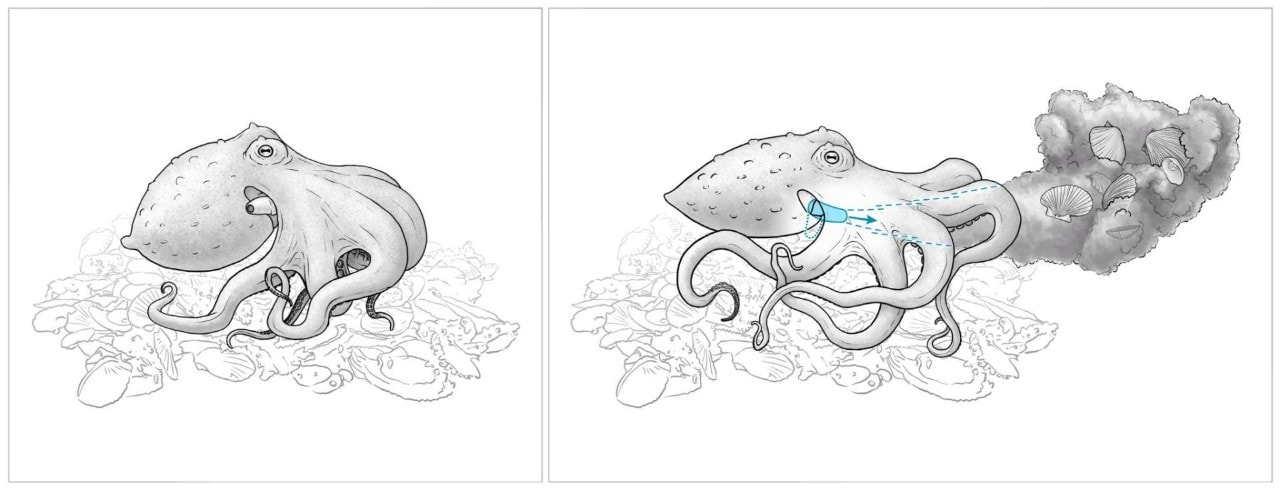

Octopuses caught on camera throwing objects [Credit: Peter Godfrey-Smith et al].

A scientist at the University of Sydney and his colleagues have observed wild octopuses throwing silt, shells and algae underwater – sometimes hitting other cephalopods.

The research was published today in the journal PLOS ONE.

In one instance, the researchers watched a female octopus repeatedly launch silt at a male that had been trying to mate with her, with the male frequently ducking to avoid the hits.

Professor Peter Godfrey-Smith, the study’s lead author from the University of Sydney’s School of History and Philosophy of Science and Charles Perkins Centre who wrote Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness, said: “In some cases, the target octopus raised an arm up between itself and the thrower, just before the throw, perhaps in recognition of the imminent act.”

Generally, females were more likely to throw than males.

During observations, octopuses also threw the remains of their meals and materials to clean their dens. There was even a case where they hurled silt towards one of the researchers’ cameras, and another two cases where throws hit fish.

But is it really ‘throwing’? It is, said Professor Godfrey-Smith, but not in a human sense. Octopuses throw by gathering material in their arms, holding it in their arm web, and propelling it using their siphon – a funnel next to their head – sometimes several body-lengths away.

He and colleagues undertook the research in 2015-2016. Using stationary GoPro cameras, they filmed up to 10 common Sydney octopuses for over 20 hours at a marine reserve in Jervis Bay, New South Wales, Australia, and later analysed the footage.

What does it all mean?

A diagram depicting how octopuses hurl silt, shells and algae [Credit: Peter Godfrey-Smith et al].

Do octopuses throw material at each other out of aggression? Professor Godfrey-Smith said this is difficult to prove: “It is tempered by the fact that there are some things we have not seen. We have not seen an octopus who was hit by a throw ‘return fire’ and throw back.”

In instances where the throwing might be interpreted as aggressive, he said this could be due to octopuses living in cramped conditions. Octopuses inhabit the site in Jervis Bay in unusually high densities, to the extent that the researchers have affectionately dubbed it ‘Octopolis’.

“Most throws do not hit others,” said Professor Godfrey-Smith. “Only a minority of cases appear to be targeted.

“I’d speculate that a lot of the targeted throws are more like an attempt to establish some ‘personal space’, but this is a speculation, it’s very hard to know what their goals might be.”

The team did however find a link between the colour of an octopus and energy of throws, building on earlier work at the site which found darker hues were associated with more aggressive behaviour.

“Octopuses that displayed uniform colour (dark or medium) threw significantly more often with high vigour, while those displaying a ‘pale and dark eyes’ pattern threw more often with low vigour.”

“Throws by octopuses displaying uniform body patterns (especially uniform dark patterns) hit other octopuses significantly more often than in other body patterns.”

Declaration: Financial support for this study was provided to PGS by the City University of New York and to DS through Alaska Pacific University from donations by the Pollock Conservation Consortium. Findings and conclusions presented by the authors are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of the supporting organisations.