Can vaping help people quit smoking? It's unlikely

Australian Health Minister Mark Butler has announced a major policy shift on vaping. Its two primary objectives are to make it harder for children and non-smokers to access vapes and to allow people trying to quit smoking to access nicotine vapes with a prescription.

Vapes are unquestionably popular, with many who vape saying they are trying to quit or to cut down on cigarettes. “Recreational” vapers of any age with no interest in quitting will find themselves frozen out.

But can vapes actually help significant numbers of people quit smoking? The evidence suggests it’s unlikely.

Myth of the ‘hardened smokers’

First, let’s bust a widely believed myth. With smoking at an all time low, some experts argue today’s smokers are the die-hard addicts: frequently relapsing smokers who just can’t quit.

Whenever this hypothesis has been tested it has been found wanting. In nations where smoking prevalence has fallen most, we would expect (if the hypothesis was true) that indicators of hardened smokers (such as average number of cigarettes smoked per day) would be rising because the remaining smokers would be over-represented by heavy, addicted smokers.

But according to a 2020 review of 26 studies:

Some have argued that a greater emphasis on harm reduction or intensive treatment approaches is needed because remaining smokers are those who are less likely to stop with current methods. This review finds no or little evidence for this assumption.

In other words, there is no evidence long-term smokers are impervious to the suite of tobacco control policies and campaigns that have driven hundreds of millions of smokers around the world to quit.

Vapes don’t help smokers cut back

The idea that vaping helps people smoke fewer cigarettes isn’t supported by the evidence. Studies of the number of cigarettes foregone by vapers who still smoke have shown that, compared with smokers who never vape, the average daily cigarette consumption is very similar.

Data from 2019 from the United Kingdom government’s annual Opinions and Lifestyle Survey also show the average number of cigarettes smoked daily by smokers who vape (8 a day) is almost identical to that by smokers who have never vaped (8.1 a day).

A 2018 paper considered the surge in e-cigarette use in England and whether this was reducing the number of cigarettes being smoked at the population level across the country. The authors concluded:

No statistically significant associations were found between changes in use of e-cigarettes […] while smoking and daily cigarette consumption. Neither did we find clear evidence for an association between e-cigarette use […] specifically for smoking reduction and temporary abstinence, respectively, and changes in daily cigarette consumption.

If use of e-cigarettes […] while smoking acted to reduce cigarette consumption in England between 2006 and 2016, the effect was likely very small at a population level.

How effective are vapes in quitting?

The most recent Cochrane review of randomised controlled trials compared vaping with nicotine replacement therapy (such as drugs, gums and patches). It found about 82% of people who vape are still smoking when followed up six or more months later.

This was better than those using nicotine replacement therapy: 90% were still smoking.

Neither nicotine replacement therapy or vapes are hugely disruptive of smoking. You certainly wouldn’t be confident using a drug for any health issue that had a 82-90% failure rate.

Randomised controlled trials also poorly reflect the ways vapes and nicotine replacement therapy are used in the real world and aren’t representative of all smokers wanting to quit.

A review of 54 randomised controlled trials on quitting smoking, for example, found two-thirds of smokers with nicotine dependence would have been excluded from clinical trials by at least one criterion. This may result in participation biases, which reduce the applicability of the results to smokers at large, or even smokers at large who want to quit.

This, and other factors, make randomised controlled trials likely to overestimate effectiveness, as I outline in chapter two of my book.

What does the real-world evidence show?

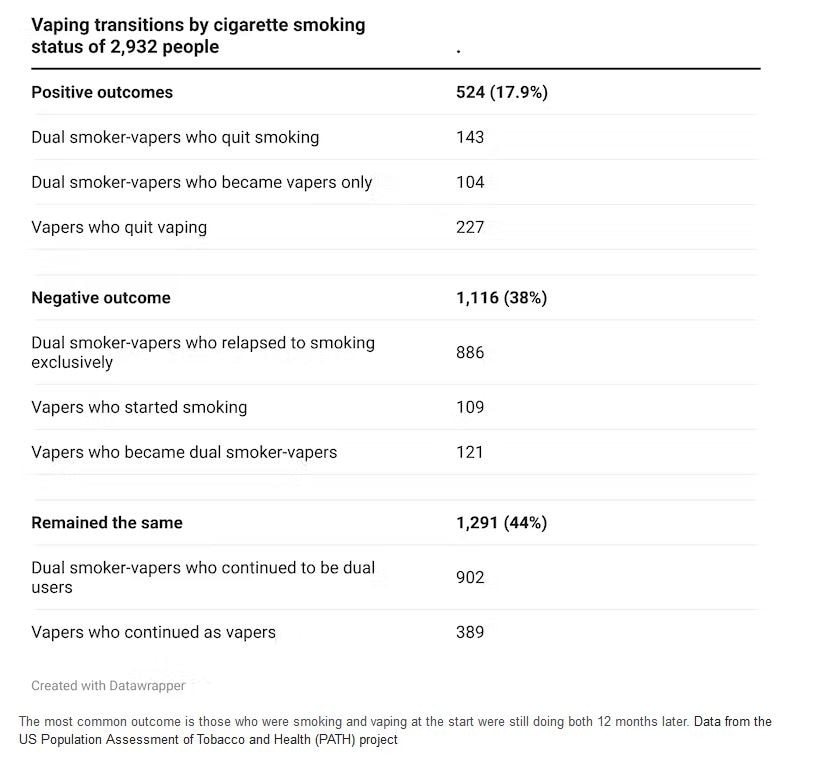

The best evidence we have about how vapes perform comes from studies where large numbers of vapers are followed for several years. The US Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) project, for example, has been collecting national cohort data on 46,000 Americans since 2013.

As the PATH data below show, when randomly selected groups of vapers are followed up at 12 months, the most common outcome is those who were smoking and vaping at the beginning of the study period will still be vaping and smoking at the end of the 12 months.

I’ve summarised 16 other reviews and expert group conclusions of the evidence published since 2017. Words like “low quality”, “inconclusive”, “insufficient”, “weak”, “low level” and “limited” abound.

The upshot?

The prescription vapes access scheme’s most important population effect is likely to be that it will massively reduce access to vapes by children. State governments will start hitting retailers illegally selling with massive fines and Border Security will do the same with importing suppliers.

Taiwan fines sellers a maximum of US$1.65 million, with a minimum of US$330,000. The current maximum fine in New South Wales is currently only A$1,600. Such a fine would barely raise dust in big retailers’ petty cash drawers.

Based on the research, we might expect 10-18% of vapers using the prescription scheme to quit within 12 months (with some relapse expected), but many more will quit unassisted.

Preventing new generations of kids from becoming addicted to nicotine and more likely to start smoking is a huge policy advance that is hugely welcome.

This article was first published on The Conversation and written by Emeritus Professor in Public Health Simon Chapman from the Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney.