How the Voice 'yes' and 'no' camps have sold their messages

The Australian Electoral Commission has just published the “yes” and “no” pamphlets for the Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum.

So who is the target audience for each case, what are their key messages, and how effective will they be?

I research how people and organisations use communication to effect change via, for example, entertainment or political advertising. When I look at the “yes” and “no” case pamphlets, there are aspects of each that stand out.

Battle of the pamphlets

The “yes” pamphlet leans on the value of expertise to help voters decide. We hear from a senator and elder, a school principal, a filmmaker, the co-chair of the Uluru Dialogues, a former High Court Chief Justice, a professor, three former sports professionals, and numerous members of the Order of Australia. Moreover, many are recognisable names, such as Rachel Perkins, Patrick Dodson, and Eddie Betts.

The members of parliament who wrote the “yes” case consider these experts to have more experience with Indigenous affairs than most voters, and are better informed about it. Their likeability and familiarity also helps put the point across to readers in a more compelling way.

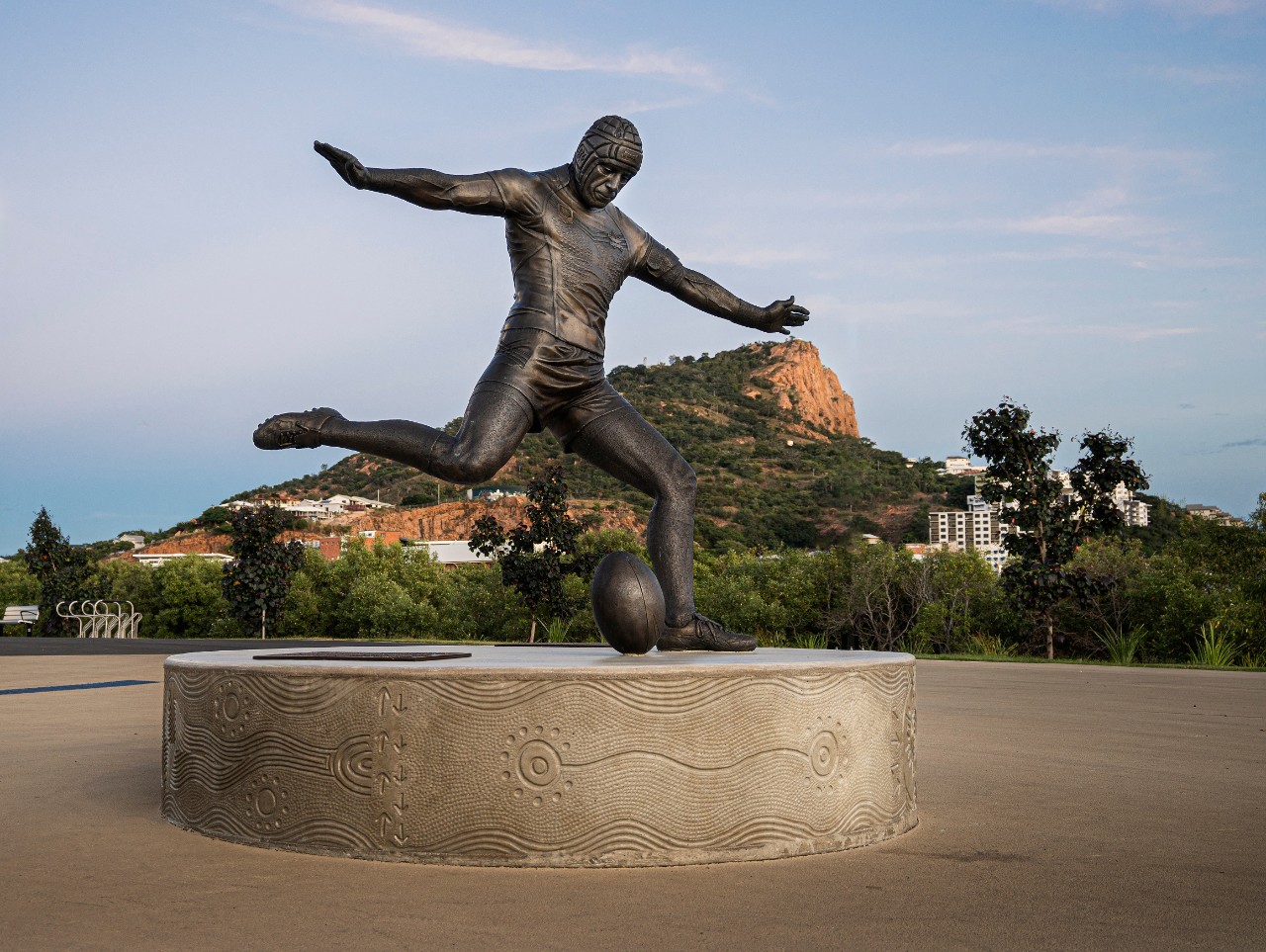

A statue of Indigenous retired footballer Johnathan Thurston outside North Queensland Stadium, Townsville. Johnathan Thurston has put his support behind the Yes campaign and features in the pamphlet. in Picture: Robert Hiette/Shutterstock

The key strategy of the “no” pamphlet, on the other hand, is “more is better”. It outlines 10 reasons to vote “no”. This is a powerful approach because the subject lends itself to it – that is, the referendum is one a reasonable number of voters really want to think about, and many have concerns about.

In general, persuasive power increases when more reasons are provided. It seems that, according to the MPs who wrote the “no” case: “the more facts you tell, the more you sell”.

Like the “yes” case, the “no” case substitutes the real question voters are being posed with another, more straightforward one. So, voters will ask themselves if the experts possess the expertise needed to provide the advice to vote “yes”. And on the other hand, voters will ask themselves if the number of reasons provided to vote “yes” is high enough and compelling enough.

Whichever has the most rational and emotional pull for each reader will win their vote.

The case for ‘yes’

According to classic research, expertise is the principal attribute of credibility. Understanding a subject and knowing what you are doing – that is, competence – enhances your credibility.

This means that if voters have the feeling a person possesses information and experience that they lack, then that expert’s viewpoint can be highly persuasive. In other words, expertise can feel like authority. This is especially so when information is hard to understand.

One study illustrates this nicely. Participants were asked to give their verdict in a mock trial. The case concerned a company suspected of having exposed its workforce to carcinogenic chemicals.

One of the witnesses was an expert, Professor Thomas Fallon. In one version of the trial, he explained in clear language that the chemicals concerned did indeed cause cancer. In another, he used incomprehensible jargon to say the same thing.

In this case, where the arguments put forward were difficult to understand, it was his expertise as a professor that proved decisive. The “jurors” understood little of the actual evidence, but felt that if a professor said it was true, then it must be true.

It is hardly surprising, then, that experts are used in the “yes” case.

The case for ‘no’

Research has shown that the “more-is-better” approach to an argument is primarily useful when the quality of a choice is difficult to ascertain by other means and there is little alternative information. In other words, the authors of the “no” case assume voters do not know how to judge whether the Voice will be a good or a bad thing, and may not consider much other information than this particular pamphlet.

It will come as no surprise to learn that people are more easily persuaded that a standpoint like “the Voice will be bad” is correct if campaigners provide strong arguments for this. You can test this yourself at work by making a simple request to people queuing to use a photocopier:

Excuse me, I have five pages – may I use the photocopier?

Generally about two out of three people asked will allow you to use the copier before them. Now make the same request, but with a reason:

Excuse me, I have five pages – may I use the photocopier because I’m in a hurry?

In that case, almost everybody accedes.

At first sight, this hardly seems astounding: people are more likely to comply with a request if they have a good reason. However, the more-is-better approach is not so much about the substance of an argument as the mere fact that one or more are given. So, for example, when you ask,

Excuse me, I have five pages – may I use the photocopier because I have to make copies?

again, almost everybody complies. That is even though they have not actually received any new information; it just feels like they have.

Other research shows people are also less persuaded by a standpoint backed with three strong arguments than by one with three strong and three weak arguments to support it.

This article was originally published on The Conversation as: Expertise v 10-point arguments: how the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ camps have sold their messages. It was written by Tom van Laer, Associate Professor of Narratology, University of Sydney Business School.