How physiotherapy alum Weh Yeoh is helping charities heal the world

I had started a physiotherapy career because I wanted to help people and loved sport. I thought I would end up working for a sporting team and working with athletes. But on one clinical placement, while working in a stroke ward with a man named John, I witnessed an amazing transformation. On his first day in hospital post-stroke, John was unable to sit independently. By the fifth week of working with him, and giving him exercises daily, he was walking independently in the hospital corridor.

Seeing this transformation made me appreciate how much allied health could change someone’s life. And yet, I wanted more. I wanted a way to help more people like John on a larger scale.

After quitting physiotherapy and packing up my life in Sydney, I travelled and lived overseas for two years. I spent six of these months volunteering in an orphanage in Hoi An, Vietnam. One day, a typhoon came in through the town and lifted the roof off the orphanage. The dormitories were so soaked that the children had to sleep on the classroom tables.

What I recall is the predominant emotion I felt at the time was not pity, or anger. It was helplessness.

And so, I decided to go back to university and study a Master of International Development. After getting a job in China, I realised that charities are often more interested in self-perpetuation than solving a problem once and for all. They, and the communities they work with, are often caught up in a cycle of dependence.

It was then that I realised that I had learnt something important in one ethics lecture in physiotherapy.

There is a difference between addressing symptoms and solving the underlying problem. An ethical physiotherapist breaks the business model, by having their patient become self-sufficient through exercises and advice. That’s the point. A truly successful physiotherapist is one who isn’t needed anymore.

It struck me that many charities could learn from this approach. Imagine if charities looked to solve underlying problems instead of addressing symptoms. Imagine if charities looked to break their own business model. We would have to redefine what a successful charity is. We would focus less on the charity and what it’s achieving now, and more on the legacy it leaves behind.

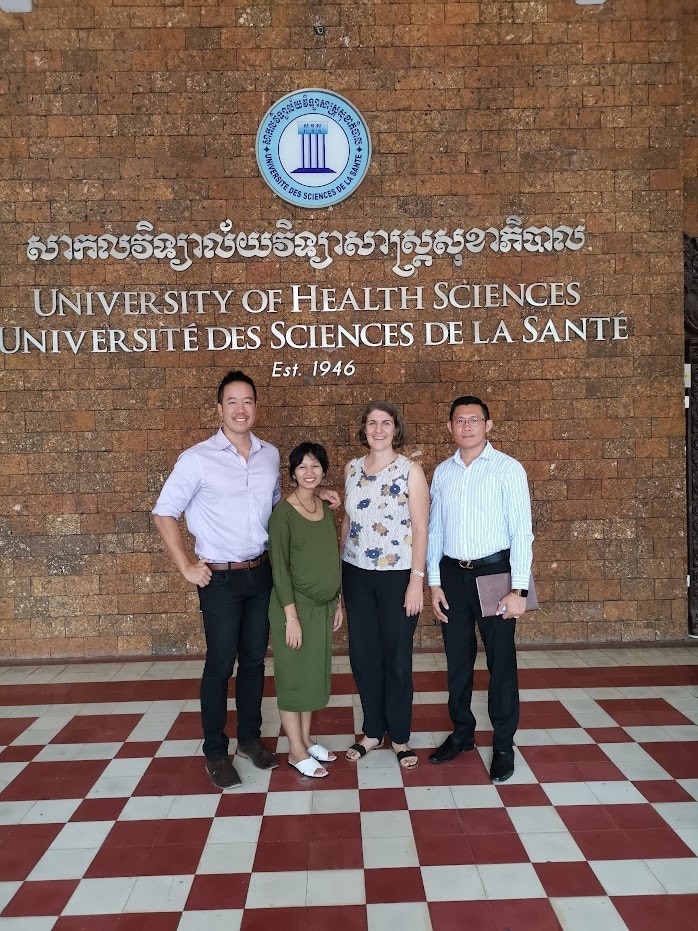

This is the method through which we started OIC Cambodia, a charity that is developing speech therapy as a profession in a country that had not one single Cambodian speech therapist. A key feature of this charity is the fact that it will shut down in 2030, when there are 100 therapists integrated into the public sector.

And for me? Even though I had lived in Cambodia for five years and gotten to a decent level of spoken Cambodian language, ultimately, I didn’t understand how to navigate Cambodia as much as someone who had spent their whole life there.

It took this thought for me to also realise that for OIC Cambodia to become redundant, I too, as the founder, had to make myself redundant. And so, after four years of leading the organisation, I stepped back from leadership so that the charity could be run by a Cambodian team. This is still the case today.

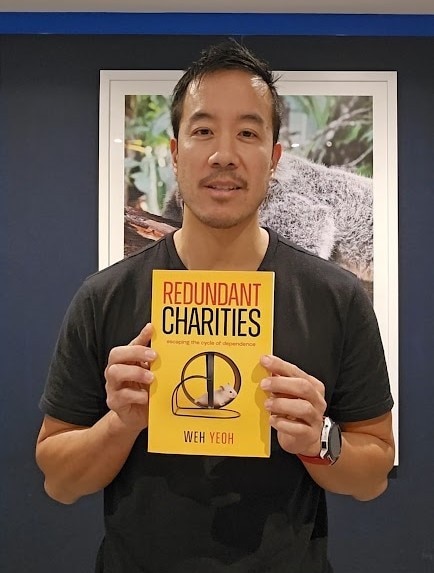

In a number of grassroots charities, change is afoot. These are charities that defy the limitations of this design by setting end goals and clear exit strategies. They are more interested in finishing the job than creating dependency. They are more interested in shutting down than growing. These charities are known as Redundant Charities.

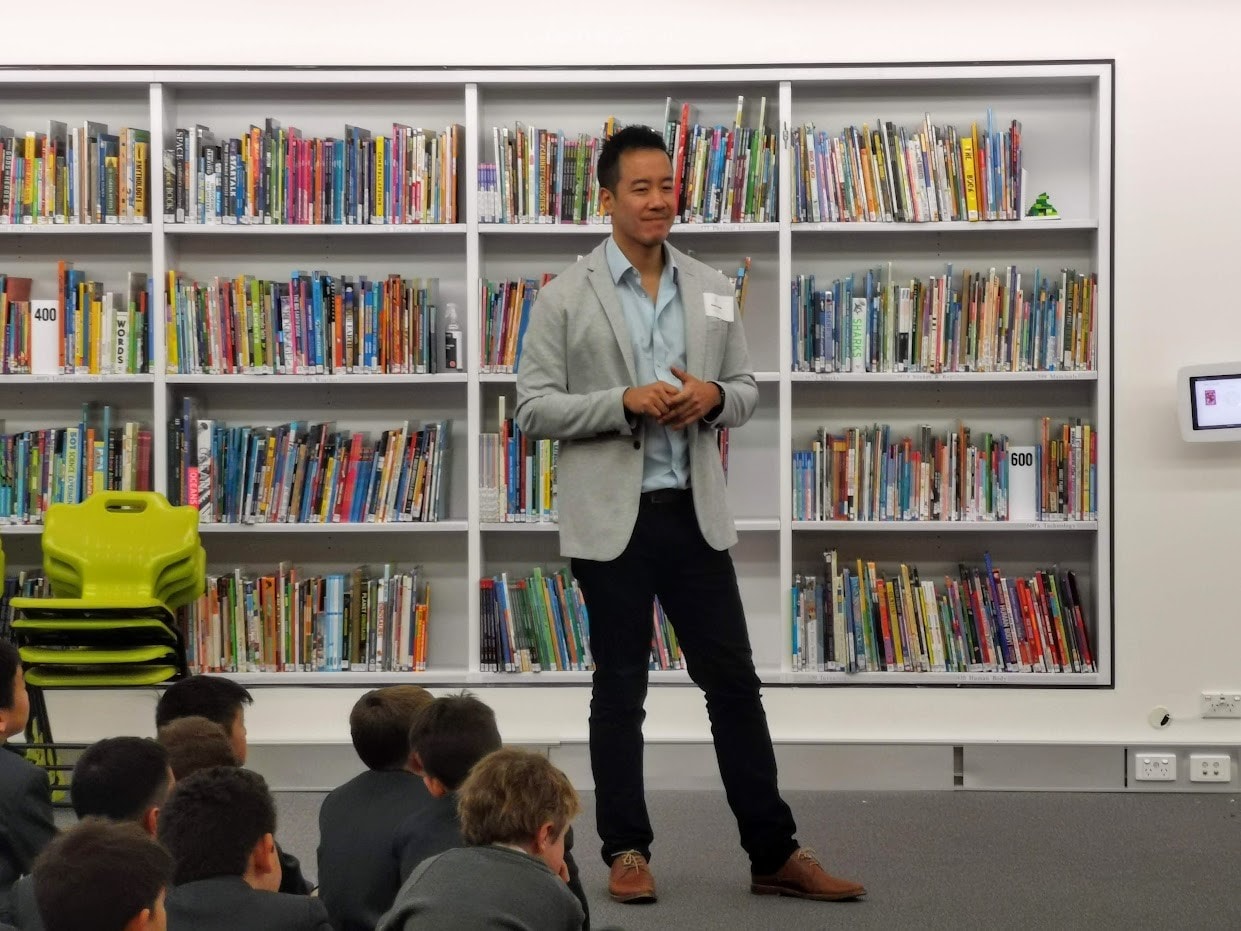

About Weh Yeoh

Weh Yeoh has worked internationally and in Australia, in the social impact space for close to two decades. He is the founder of OIC Cambodia, an initiative that aims to establish speech therapy as a profession in Cambodia. He has a Bachelor of Physiotherapy from the University of Sydney and a Master in Development Studies from the University of NSW.

He has volunteered with people with disabilities in Vietnam, interned in India, studied Mandarin in Beijing, and milked yaks in Mongolia. He started OIC in 2013, and handed over leadership to a local Cambodian team in 2017. He has since co-founded Umbo, a social enterprise bridging the gap for rural Australians to access allied health services.

Weh Yeoh's first book, Redundant Charities, has just been released globally. It discusses the structural issues that face charities, and promotes a new model of charity - one that makes itself redundant.