In our defence

As a child in Siberia, Dr Helen Cartledge (PhD (Engineering) ’98) would trek 10 kilometres through the snow to school and back again every day, as temperatures plunged below minus 40 degrees Celsius, encountering the occasional steppe wolf along the way. At night, she and her three siblings would curl up on a bed made of river stones to do their homework by candlelight, and their mother would tell them, “If you don’t study science, you won’t understand the world.”

“Life was hard, but mum never let us forget that we had come to this world with a mission. She would say, ‘Science can save the world"

For the oldest of four siblings, growing up in a mud and straw house in a mountain village in southern Siberia, without running water or electricity, ‘the world’ seemed a fairly remote concept. By comparison, opportunities to explore science were ever present.

When the family moved to a nearby city for school, they would conduct science experiments and build all kinds of devices – from crystal radios, to turning a bicycle into a doorbell, to making a transformer that could change the voltage from 110 AC to 12 DC. “We thought it was the first transformer ever built in the world,” Cartledge laughs.

Life in the city, however, was marred by pollution, with strong chemicals blowing across from nearby Russian-built factories. “Some days, the washing would be covered with black particles. The river that used to be full of fish and crabs turned black and smelt of benzene,” Cartledge recalls. Not long after they moved to the city, her mother died of lung cancer. She had neither smoked nor drunk alcohol.

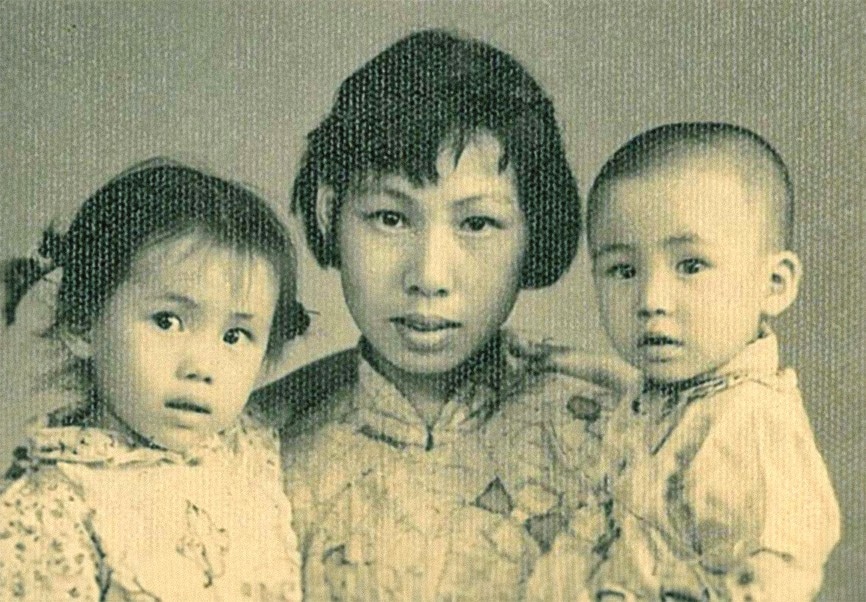

Dr Helen Cartledge with her sibling and mother.

Cartledge’s early experiences would spark a life-long quest for scientific answers – and lead her to Australia and along a diverse career path from mining industry engineer to senior science adviser in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, and deployment to the Middle East with the Australian Defence Force. Her contribution and leadership in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) has also been recognised with accolades including 2019 Australian Professional Engineer of the Year and a 2017 Service Medal for her deployment.

Cartledge and her siblings moved to Sydney in the early ’90s, all graduating with degrees from Australian universities. With the support of the federal government and University of Sydney scholarships, Cartledge attained a PhD in materials engineering, while her sister, Professor June Watzl, gained a PhD in medicine with a focus on cancer research, inspired by the loss of her mother.

Taking up the challenge

“I developed not only my foundational knowledge at university but also learnt about the Australian lifestyle, culture and people. And, most importantly, it taught me a desire for excellence,” Cartledge says.

“All throughout my professional career I have never let any work leave my office without giving it my very best effort. It gave me confidence, ambition and ability to serve this country and the world.”

But the reality was tough. Cartledge says it was difficult to find a job after graduating. “I quickly learnt that no-one needed me to save the world. I couldn’t even save myself,” she says. “As a female engineer with an Asian appearance, people assumed I was incompetent.” Cartledge’s chance to prove herself came when she was offered a position at a small mining consulting company . She was given a problem they’d been trying to fix for years: why the 280 tonne caterpillar trucks kept breaking down in a high-altitude mine. Cartledge solved it within 10 days.

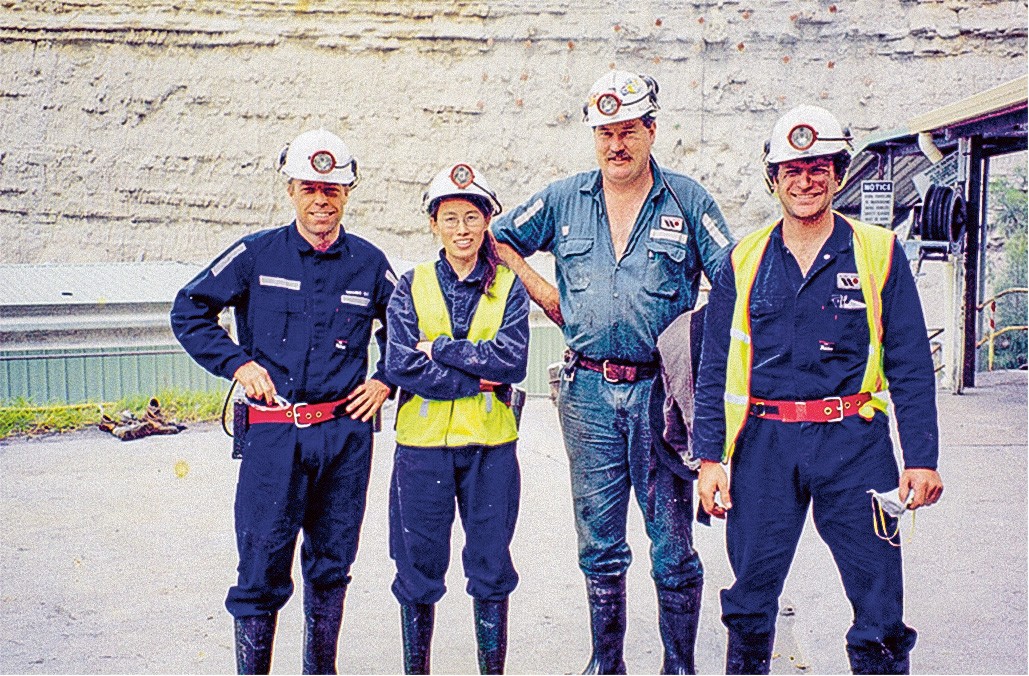

Cartledge in her first job out of university, as a mining industry engineer.

Her reputation grew. But she was also faced with a choice. An application she had made to Australian Defence had been accepted. Cartledge saw it as a way to repay Australia for the new life it had provided. Now in a head of engineering and logistics role within Defence, delivering cutting-edge capabilities to the Royal Australian Navy, she says it is a dream job for any engineer.

“Technology is only one part of the job; it requires not only intellectual leadership but also people leadership to bring the best out of the people around you,” Cartledge says. “When you give credit to the people working for you or with you, some amazing things will happen. And it’s important to be positive, persevere, and to be flexible and adaptable. Engineers can tend to be rigid, but the world is not just black and white. There is a whole rainbow of colour in between.”

She urges young engineers to take up the challenge.

“Don’t just make a living, make a life and make a difference! I have had many challenges and sleepless nights along the way, and I constantly ask myself and my team when we make decisions: ‘Are we delivering the right capabilities to our Navy? Are we acting in the best interests of taxpayers?"

Like her sister, Cartledge has always been strongly motivated by her mother’s life – and death – and she has never stopped searching for answers, including the cause of her mother’s cancer. “I’m determined to find solutions to fight pollution in air, land and sea,” she says.

With her understanding of polymers, gained during her PhD, she worked after hours in her backyard laboratory to build machinery to convert human-made waste, such as packaging and cloth, into useful materials.

“Twenty-five years ago, people told me that my technology was worth a lot of money.” Cartledge says. “I knew that if I had patented it, no-one would be able to afford to recycle the waste materials.” Instead, she has shared her designs and her green composite technology freely with universities and factories in developing countries. And she spends her annual leave travelling around the world to teach people to use it.

She urges other inventors to be conscious of introducing new technology to improve lifestyles, while at the same time considering the risk of a longer-term catastrophe.

“Scientists are given funding by industry to search for solutions. It’s important for researchers to maintain the bigger picture, to consider broader humanity and universal benefits, to ask the question: What are the consequences of science’s side effects?”

All these years later, she’s still pondering her mother’s adage: ‘Science can save the world.’ “But I would like to ask, can the world save good science?

I now realise that science alone cannot do this,” she says. “It is not a simple matter for any individual scientist to influence research priorities. The right policies and leadership are needed at the government, corporate and academic level to nurture science and ensure that we have a healthy labour market. This is how we encourage younger generations to take up STEM.”

Cartledge was named 2019 Australian Professional Engineer of the Year.

A passionate advocate for STEM education, Cartledge has chaired Defence Science and Technology Scholarship panels to support female students to pursue their dreams, she is a PhD thesis examiner for numerous universities, and volunteer teacher in schools. Her classroom has stretched from Canberra to Sri Lanka and Tibet.

“We need to grow our country’s STEM workforce and make it accessible to students from all walks of life. Research funding will repay the economy exponentially,” Cartledge says.

“I went on my journey to save the world. The mission my mother gave us has not been accomplished yet and I’m still on that journey with people who have the same drive, including my sister, my colleagues and hopefully future generations.”

Written by Eleanor Whitworth. Photography by Stefanie Zingsheim

Read the latest edition of Sydney Alumni Magazine.