What can we learn from nature if we listen to it deeply?

Listening to Earth: "deep listening"

Entering a darkened room filled with sound, student Manvi Saxena took off her shoes and lay down on a bench. Closing her eyes, she listened to the rumbling sounds of waves captured by microphones positioned deep underneath sand dunes and underneath the sea, alongside the wind high overhead and droplets of water moving in small rock pools. She may have even listened to rhythmic sounds coming from a starfish – perhaps a heartbeat?

Beneath her, Saxena could feel the vibrations of the sounds in the bench that glowed softly in the room. For around 20 minutes, she was immersed in Listening to Earth, a “deep listening” experience and sound installation created to encourage visitors to focus on listening, connecting, and understanding our environment through the medium of sound.

Student Manvi Saxena

“This was my first time experiencing something very deep and meditative, I was listening to the Earth and I could hear the sounds and the vibrations. I could picture that I am deep inside the Earth, it was really amazing and a wonderful experience,” said Saxena, who is a commencing student from India enrolled in Masters of Commerce.

“It made me feel very calm and composed,” she said. “We are so busy in the hustle and bustle of life we don’t have the time to relax and listen to the environment. It’s the best way to learn about it.”

Listening to Earth

Listening to Earth is a research project by Associate Professor Damien Ricketson from Sydney Conservatorium of Music and Dr Diana Chester, from Media and Communications, who both work with sound as their primary medium. Together, the researchers captured sounds from beaches around NSW and composed the recordings into a 40-minute work of sound art where listeners can come and go, and either sit, stand or lie down on benches with cushions.

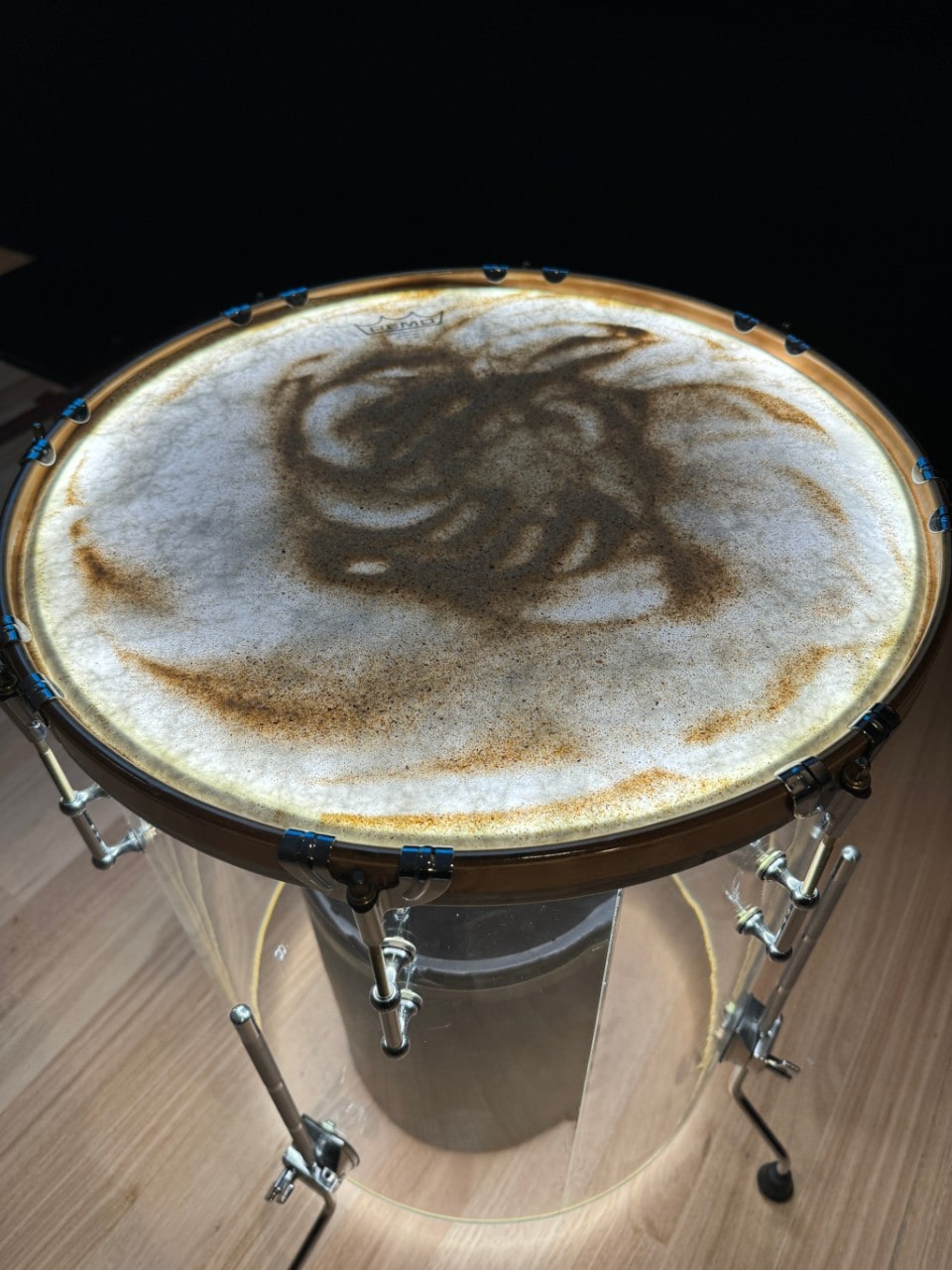

The immersive spatial experience surrounds the listener with sound, allowing them to feel the sounds in their bodies through vibrations coming from the benches, and to visualise the sound with drums that vibrate grains of beach sand until they bounce into the air. The work is enhanced by a visual artwork that responds to the sound by video artist Fausto Brusamolino.

Visual art by Fausto Brusamolino.

“What Damien and I are doing with this project is allowing listeners to hear the sounds they don’t usually hear,” said Dr Chester. “In rock pools, for example, we can see the diversity of marine life in the pool, but we don’t stick our ear into it – we don’t want an octopus or some other creature to come and bite us! There is a safety element.

“Instead, what we are trying to do here is to bring the sounds of the rock pool to the people. We’re trying to help people have their ear in a sand dune or to be 10 feet out in the ocean, sitting on the ocean floor, and listening to what that actually sounds like. People can then begin to simultaneously make sense of what they see in the world around them and how that world sounds.”

Associate Professor Ricketson said the work contains an important message about the environment and how it is changing: “Artists can amplify climate science messages by creating empathic experiences that enable the environment to tell its story through media other than the written word. This deep listening experience allows the environment to speak to us in a visceral way. Music and sound can bypass the brain and act on the body.”

“We are aiming for a better understanding of the environment and the changes that are happening and how to communicate the urgency of those changes,” said Dr Chester. “We are trying to encourage people to listen more deeply, to pay attention. The learnings here are not the same as what we might publish about our research in a peer-reviewed journal, but I think these are as important or more important.”

Listening to the environment

The recordings for Listening to Earth were captured at Cudmirrah Beach, three hours south of Sydney, Maroubra Beach in Sydney, and the lighthouse headland at Nobbys beach in Newcastle. The sounds were captured using microphones, hydrophones (underwater) and geophones (under the sand), as well as custom-built Aeolian Harp inspired listening instruments to capture the wind.

“We had a few interesting discoveries from under the water or under the sand,” said Associate Professor Ricketson. “I was surprised when I stuck a geophone into the sand dune - it was so noisy down there. It was interesting to hear sand grains move in a sound that was more evocative of wind – the particles of sound.

“We have a recording that Diana got from a rock pool with a hydrophone that is most certainly a starfish, but we don’t know what in the starfish is making the sound. Is it a heartbeart? There is some debate about whether a starfish has a heart or not. It’s a microscopic sound.”

Recording the sounds of nature

The sounds were later composed and spatially reconfigured in a Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences audio editing room. The room has eight speakers at various heights to create a surround sound experience, that when partnered with a sub woofer, and spatial audio software, allowed us to create the soundscape.

“The speakers play back sounds in our audible range that we’ve captured and positioned in this spatial environment,” said Associate Professor Ricketson. “We’re also using bass shakers and custom-made sound canons to recreate some of the lower frequency sounds in these environments that are typically beyond our thresholds of awareness.”

“For example, the low rumbles deep beneath the sand come into the benches as seismic vibrations. So, if you are sitting or lying on one of these benches, you will hear those sounds with your body in a tactile sense rather than through the ear,” he said.

“We are also using sound canons underneath drums with sand from the beach placed on the head of the drum, and it vibrates the head of the drum. So, sounds originally from the sand reanimate the sand as it bounces on the drum.”

Sand from Cudmirrah Beach vibrates on the drum head.

Dr Chester said the low-end sub and bass shakers give the perceptual feeling of a sound: “Like when you go to a club or a concert, and you get the whvoom, whvoom whvoom feeling in your chest.”

“Then we have speakers that play back the mid and high range sounds, these are placed on the floor about two metres up, and these give us the ability to perceive sound in a spatial cube from the floor up to two metres high, and the sound is surrounding us in a 360 sphere,” she said. “Then we have the speakers that are vibrating things, including the sand and including ourselves through the benches. The idea is we have layers of sound that replicate the planes of the physical world. From the sand that vibrates beneath your feet, to the ocean waves crashing, to the wind that gusts in the sky above.”

The ideal listening positions is on the benches, added Associate Professor Ricketson: “there you can take advantage of the spatial sound mixing in the cube with the added layer of vibrational information beneath you.”

Collaborative Study

Researchers Damien Ricketson and Diana Chester. Photo: Stef Zingsheim

Listening to Earth was created as part of a Collaborative Research Fellowship awarded through the Sydney Environment Institute. The installation was presented in its first showing at the Chau Chak Wing Museum by the Sustainability Team in February, and hopes to have second viewings at galleries around the country in the coming year.

The researchers have presented their work at conferences and erected a smaller scale installation in October 2023 in Singapore at the Yong Siew Toh Conservatory of Music. They are hoping to collaborate with researchers around the world.

“We aim to bring other scholars and creatives into the conversation about how we can think about listening to our world where humans are not at the epicentre,” said Dr Chester. “For us, bringing a very close deep listening attention to sounds of the environment is a way to allow the environment to tell its own story.”

Top photo: Aerial image of breaking waves at Redhead Beach in Newcastle, near where the recordings of wind were made. Credit: AdobeStock