The sovereignty and science of the skies

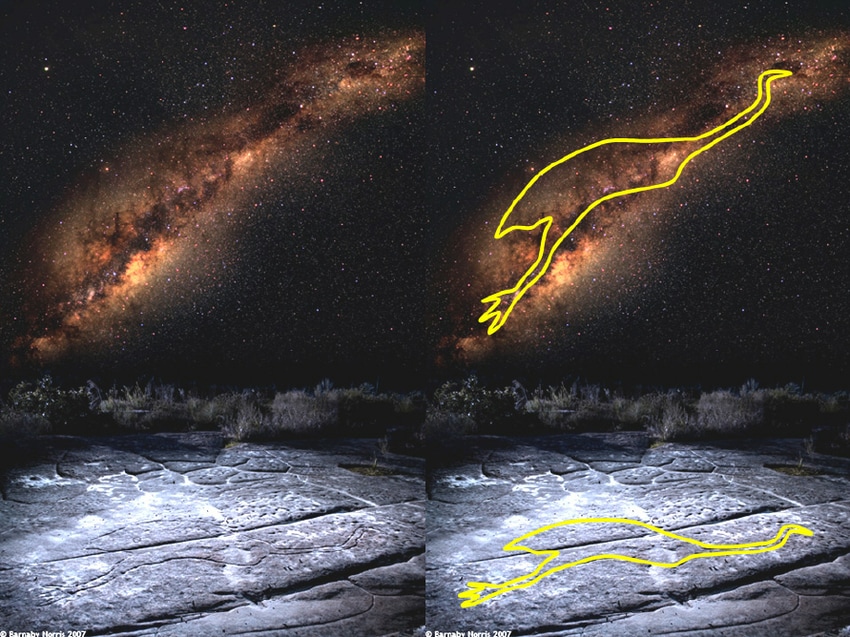

The Great Emu in the Sky and the Ku-ring-gai National Park sandstone engraving. Picture Courtesy of Barnaby Norris, 2007.

My D’harawal father is a captivating storyteller and some of my earliest memories are of him telling us stories. Some of our favourite stories were about the sky.

On hot burran (summer, kangaroo season) nights we would escape the fibro heat to float in our suburban backyard pool and watch the stars “gili gili” (sparkle, shine or illuminate). Connected to the water and the earth we would find our connection to the skies and talk about stars, planets, Min Min lights, Ancestors from the sky, Creation Spirits and the Dreaming. My father taught us about astral travel and it is through discussions about other dimensions and planes that he finds the words to describe the Dreaming and the stream of knowledge and conscientiousness that connects us to our Ancestors.

Our connection to the skies is as strong and palpable as our connection to the earth, the water and the animals that exist not just with us, but as a part of us. While others see the skies as a void or vast expanse of nothingness, we see the skies as an integral part of our knowledge systems and of the continuous, circular attachment to each and every rock, drop of water or breathing creature. We don’t see the world as separate layers, environments or ecologies divided into the earth, the seas and the skies. For us, it is all one complex and intricate web intertwined with stories and knowledge. Every single aspect affects the next and existing within that circle means that whatever you do comes back to you – a core belief that ensures the survival and sustainability of every aspect of the world and a lesson that needs to be lived now more than ever.

We do not own the skies, the land or the water - we belong to them. The natural world controls us and we must read the signs it gives us in order to know what to do and, importantly, what not to do. The sky tells us how to navigate the earth and it gives us information about the seasons, the weather, what is coming and what has been. It is our access to the skies that keeps our culture and our knowledges alive. We know the skies so intimately we study not only the light of the physical stars but also the dark spaces in between like that of the Coalsack in the Milky Way which creates what we know as the Great Emu in the Sky who tells of different seasons and what to do at particular times.

Our sovereignty of the skies is often overlooked in discussions of Indigenous “land” rights and the skies have also been colonised in much the same ways as our land and our knowledges. Because of the land clearing and development of urban areas the resulting light pollution means I can no longer see the same celestial bodies that I could see as a kid when I was floating in our pool with dad. In many places now the sky is barely visible at all through the canopy of glass and steel of a city scape. Rumbling aeroplanes and horizons of smog all alter how we see the world above us and interpret the Country around us. How do we hold on to our knowledges when we can no longer access it?

In the 1960s when the first moon landing was at the forefront of the global collective consciousness, Indigenous Australians were fighting for citizen rights on their own Country. It is hard to reconcile the fact that we just wanted to be able to walk freely on the earth while the science world was preoccupied with walking on the moon.

The importance of the skies to our culture has been acknowledged recently through a government education initiative that is worth a look. The Curricula Project aims to assist teachers in embedding Indigenous perspectives into the classroom through the three themes of astronomy, water and fire. Teaching guides for astronomy have just been released and you can still contribute to the evaluation of this aspect of the project.

Now, decades later in the same suburban backyard (though the pool is long gone), my father and I are still having conversations about our skies and I am still learning from him and hearing new stories. The question now remains though, will my children be able to learn from our earth in the same ways that I did? What will be left for them to learn from?