Classics never date

Some companies look for job candidates with degrees in ancient languages because of their problem-solving skills. But many people seek out the Department of Classics and Ancient History simply because the classics are fascinating.

The world’s most widely spoken languages, in rough order, are Mandarin, Spanish, English, Arabic, Hindi and Russian. Latin and Ancient Greek don’t make this list – they’re not even among the top 100.

But dead? Hardly. The New Testament was written in Ancient Greek. I, Claudius, a mini-series about the Roman Empire, was big on the small screens in 1976. Remember The Secret History, Donna Tartt’s bestselling novel from 1992? Her central characters were a group of classics students. Harry Potter author J K Rowling studied Latin and based Dumbledore on one of her professors. Then there’s Gladiator (2000); Troy (2004); and 300 (2006): all big blockbusters reflecting a lasting interest in the ancient world.

Funerary monument. From Rome, Italy, 1st century AD. NMR.1118, Nicholson Museum.

Even Westpac Bank has been known to seek out graduates with ancient languages on their CVs because of their problem-solving ability. Former Westpac chief executive Gail Kelly taught Latin in South Africa before embarking on her renowned banking career.

The University of Sydney isn’t immune. Every year, the Department of Classics and Ancient History welcomes up to 100 students into its Latin and Ancient Greek programs, and more than 500 into its Ancient History units. The University’s January Latin Summer School attracts more than 200 students aged 14 to 90 from across Australia. There are sold-out stagings of Greek tragedies and extracurricular Latin reading groups for students who wish to keep up their skills.

“People love Latin,” Senior Lecturer in Classics Dr Bob Cowan says. “They have a massive appetite to learn it.”

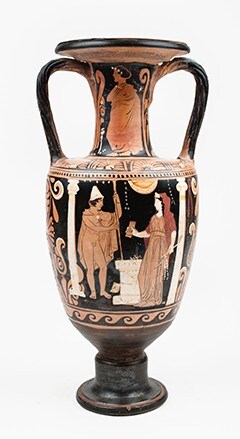

From Campania, Italy, 350 325BC. NM51.17.

Senior Lecturer in Latin Dr Paul Roche agrees. “Latin is a blueprint for understanding other languages,” he says. “It’s behind French, Italian, Spanish and the other Romance languages.” PhD candidate Irene Stone (BA(Hons) ’12 DipLangStudies ’14), whose work focuses on speeches and speech making in Herodotus’s Histories, adds: “The ancient languages assist in the ability to write good English.”

The notion persists, however, that studying these languages is difficult. Dr Roche sees it differently. “Latin has a very clear grammar,” he says. “There are a lot of grammatical rules in Latin, and that initially takes a bit of getting used to. But once you’ve got them under your belt, the more rules a language has, the less ambiguity it has.”

Dr Roche has taught students who use Latin as a research tool for ancient history; those who are curious about the literature of the period; and English majors interested in the deep roots English has in Latin. “We have scientists and of course law students – a lot of the law’s technical terminology is in Latin,” he says.

Ancient languages are also a key that unlocks the classics. “This is the study of the great civilisations of Ancient Greece and Rome – their history, literature, archaeology,” Dr Cowan explains. “They are endlessly fascinating periods in themselves, but also have had an immense influence on Western – and world – civilisation ever since.”

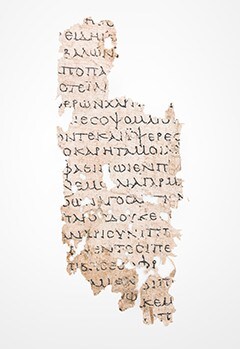

From Egypt, 2nd century AD. NM39.5.

Dr Cowan believes the classics are a great way to delve into the hearts of cultures that were simultaneously like our own and yet strangely alien. “One moment we feel as though we’re having a goblet of wine with Horace, discussing life and love,” he says. “The next we’re watching a Roman general cancel a battle because the sacred chickens aren’t eating their corn properly.”

For Dr Roche, the joy of Latin is in its literature. “It was produced by a group of people who had such a depth of feeling for the human experience,” he says, citing the poets Virgil and Horace as particular favourites. “They answered ethical questions that are still relevant today – they’re in the same category as Homer, Dante or Milton.”

Dr Roche is careful to point out that while we have this wonderful treasure trove of literature, it comes largely from a privileged male point of view, so we need to exercise caution when using these texts to recover the experience of women and minority groups such as slaves and foreigners. Even so, he adds, some female voices survive directly to us in the poetry of Sulpicia in Latin and Sappho in Ancient Greek.

Dr Paul Roche, Irene Stone, Dr Robert Cowan.

Studying the classics embodies the University of Sydney principles of nurturing deep and specialised knowledge while exploring new thinking. “Classics is the original interdisciplinary subject,” Dr Cowan says. “History, literature, philosophy, democracy, art, archaeology, politics, language, linguistics, theatre studies, gender studies – all are an integral part of classics.”

In person, all three of these scholars exude what Stone calls the “pure magic” of engaging with ancient texts in their original form. But in the more earthly realm of careers, where does a graduate with a classics degree go? “This sort of study – ancient history combined with an ancient language – ensures a student not only covers the exacting task of learning an ancient language, but also becomes adept at pinpointing and solving problems,” Stone says.

Graduates go into law, commerce, public service, as well as academia and teaching, Dr Cowan says.

Stone adds: “Any number of modern careers will benefit from a knowledge of ancient history, Latin or Greek – law, maths, architecture, medicine, international diplomacy.”

Fancy revisiting your classical studies or taking up a whole new interest?

Carpe diem

Written by Monica Crouch

Photography by Stefanie Zingsheim