A gift in kind? How kind! The weirdest donations to the University

A Picasso wrapped in plastic. A beetle as big as a rat. Gruesome medical gadgets. Over the years, generous benefactors have given the University of Sydney a rich and rare array of donations in kind.

Think your relatives give strange Christmas presents? That mustard-coloured balaclava from Aunty Beryl is nothing compared to some of the gifts the University of Sydney has received from its benefactors. The University can only accept gifts in kind when they add something unique to its collections and archives. That makes every object on this list a gift to be treasured.

A jar full of rats

The so-called Hapalotis arboricola rats. Photo: Macleay Museum

The natural history collection at the Macleay Museum is full of beauty, from cases full of butterflies to a stuffed mouse-deer (an elegant hoofed creature about the size of a Jack Russell terrier). Then there’s the jar of rats. They’re packed in tight, fur damp with preserving ethanol, fleshy white tails coiling around the jar’s glass walls. It’s just as disgusting as it sounds. Like many of the museum’s objects, the rats came to the University as a gift in kind from the Macleay family, who donated their extensive collection, along with funds for a curator, in the late 19th century. Taxonomist William Sharp Macleay collected the rats thinking they were a new species, Hapalotis arboricola. John Gould duly published them in his famous Mammals of Australia. It turned out they were plain old Rattus rattus, as common a rodent as they come.

A mummified baby crocodile

Photo: Nicholson Museum

During his life, this little guy would have been one of the best fed crocodiles in Ancient Egypt. As a sacred creature living in a temple dedicated to the crocodile god, Sobek, he would have been cared for and revered. As such, after his death he was entitled to the burial rites that have kept him in good nick for more than 1600 years. His body was packed in salt, treated with a bitumen compound, then wrapped in bandages to be buried in company with a larger, fully-grown crocodile mummy.

Animal mummies were so ubiquitous in Ancient Egypt that there are stories of them being burnt as railroad fuel in the 19th century. This baby croc avoided that fate and ended up on the antiquities market, to be bought by Sir Grafton Elliot Smith, a Sydney alumnus who carried out archaeological and anthropological research in Egypt in the early 20th century. The mummy stayed in his family until 1984, when his great-nieces, Miss Elizabeth Bootle and Mrs Elwyn Andrews donated it as a gift in kind to the University of Sydney’s Nicholson Museum, where it remains on display.

A Picasso in a plastic bag

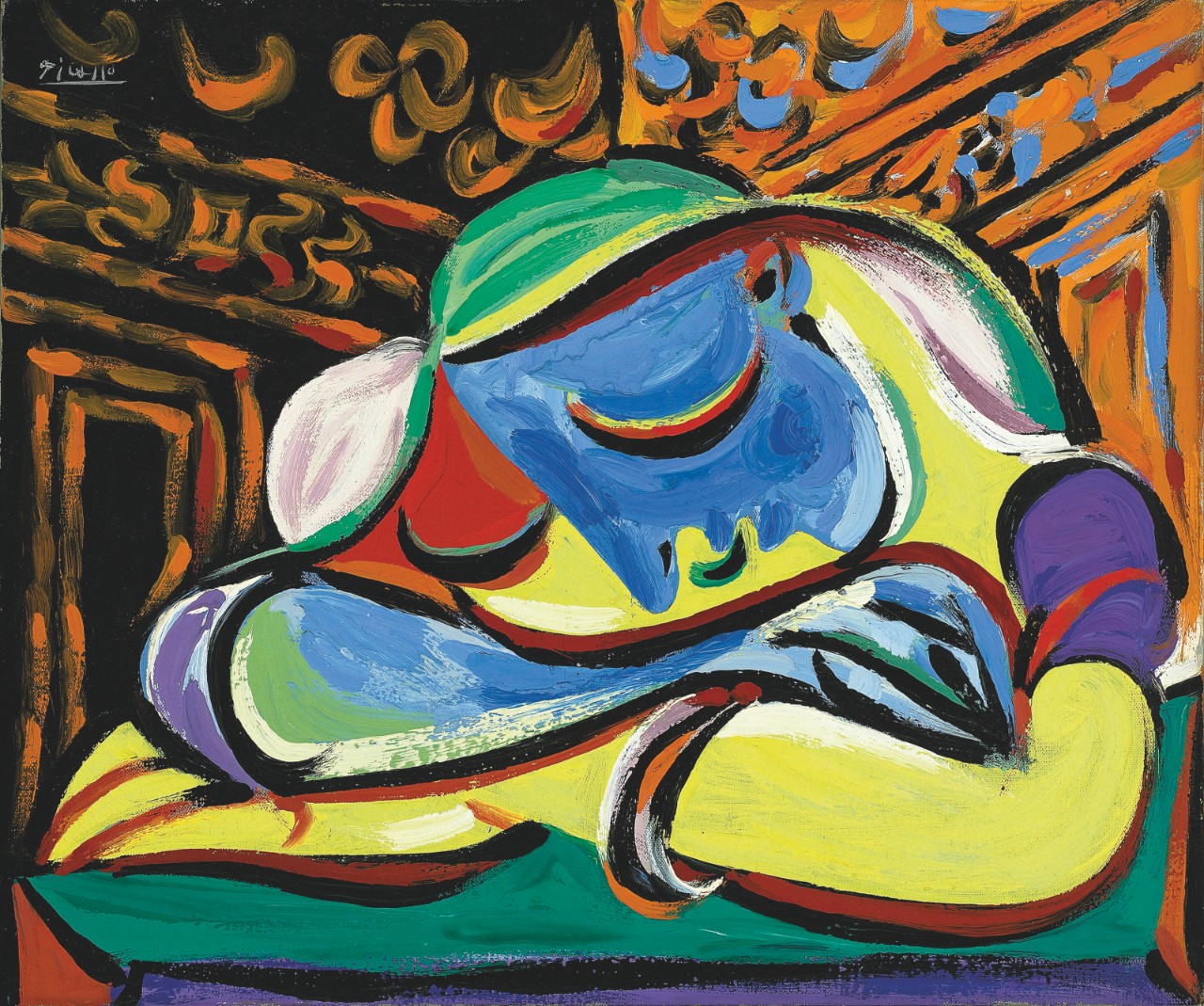

Pablo Picasso's Jeune Fille Endormie (1935)

Tim Dolan, the University’s Vice Principal (Advancement), will never forget the day in 2010, when an anonymous American philanthropist arrived in his office with a Picasso masterpiece wrapped in a plastic bag. The work, Jeune Fille Endormie, had rarely been seen in public and was given to the University on the condition that it be sold, with the proceeds directed to medical research. Over lunch in Newtown, the donor told Dolan: “When you own a valuable painting like this, it sort of owns you back. For the first time in a long, long while, I finally feel free.”

The painting’s $20.7 million selling price has already funded three research chairs at the University’s Charles Perkins Centre, supporting work in the fields of nutritional ecology, metabolic systems biology and psychology. A fourth chair in obesity science will soon be established as a result of the gift. The Picasso donor made a further gift in kind of jewellery and paintings, which were sold for the benefit the University’s museums and art gallery.

A tiny chainsaw for slicing through human skulls

Photo: Sydney Medical School Heritage Collection

For an object with such a gruesome purpose, the Gigli saw is elegantly designed. Its flexible, sharp-toothed blade threads through two holes drilled in the skull before being attached to two handles to saw upwards through the bone. The device was invented in 1893 by Italian obstetrician Leonardo Gigli, to slice through the pubic bone during obstructed labour. It was later adopted by neurosurgeons (who are still using a more contemporary version of the design). This particular device is a gift to the Sydney Medical School Heritage Collection from Clinical Associate Professor Catherine Storey, along with a vast collection of historical medical implements owned by generations of doctors in her husband’s family. The saw belonged to her husband’s grandfather, a Prince Alfred surgeon who served in World War I, attending the wounded of Gallipoli.

A home-made harpsichord

Photo: The Sydney Conservatorium of Music

Think building IKEA furniture is tough? Try constructing a harpsichord from a kit. The keyboard instrument (all the rage during the 17th and 18th centuries) makes music thanks to a complicated arrangement of keys, strings, pivots and plectrums. Building a harpsichord from a kit of ready-made parts is the ultimate DIY challenge for Baroque music buffs. The Sydney Conservatorium of Music is the proud owner of one such home-made creation, thanks to an in-kind donation from the Marsh family of Darling Point. The instrument was a labour of love for Geoffrey Marsh and when he died, his family wanted it to go to a good home. Neal Peres Da Costa of the Con’s historical performance division was delighted to accept the gift, which would have cost up to $50,000 to buy. It’s regularly used in concerts and, says Peres Da Costa, “it’s a nice instrument for our students to cut their teeth on”.

A large gold nugget shrouded in mystery

Photo: Macleay Museum

When someone gives you a valuable gift like, say, a historically significant gold nugget, you put it away somewhere safe. In 1892, Lady Susan Macleay, daughter of Chancellor Sir Deas Thomson, gave the University of Sydney the nugget believed to have sparked Australia’s first gold rush. It was tucked away in a strong room at the University until 1955, when a photograph was taken of it for the University’s Gazette. Back into the storeroom it went, a place so safe that for decades, no one had any idea where it was. When the gold was rediscovered after an investigation in 1983, it was a different shape from the original, and about three quarters of an ounce lighter. “There is this real mystery about this nugget and why someone would tamper with it,” says Jude Philp, senior curator at the Macleay Museum.

The nugget – first discovered in 1851 at Ophir, NSW – was large enough to prove the existence of payable gold in Australia. Accordingly, it was sent to Deas Thomson, then the Colonial Secretary. It got its illustrious historical pedigree through the (now disproven) assumption that Lady Macleay inherited the treasure from her father.

The world’s biggest bug

Photo: Macleay Museum

No, it’s not a gigantic cockroach. Titanus giganteus is the largest beetle species in the world. This hefty specimen is approximately 16 centimetres from head to tail – about the size of a large black rat. She has come a long way to join the Macleay Museum’s collection; first acquired in the 1770s by French politician Pierre-Victor Malouet during his work in the colony of French Guiana, then captured (along with Malouet and the rest of his ship) by state-sanctioned English pirates on the way back to France. She was eventually sold at auction, and passed between a few collectors before being purchased in London by gentleman naturalist Alexander Macleay for five guineas (about eight weeks’ worth of wages for a labourer at the time). When Macleay moved to New South Wales to serve as Colonial Secretary in 1826, his large and valuable insect collection went with him. It came to the University when the Macleay family donated their collections in the late 19th century.

A gigantic stained-glass window

Photo: Clive Jeffery

When Sir Philip Sydney Jones, Vice Chancellor from 1904 to 1906, donated these stained-glass windows to the Anderson Stuart Building, he probably did not envisage that they would one day be the defining feature of a men’s toilet. Building work in the early 1920s locked the windows behind a brick wall, so they could only be seen from inside a male bathroom on level five. Associate Professor Kevin Keay, head of anatomy and histology, says occasionally women in the building were invited into the toilets for a look. That’s no longer necessary, thanks to renovations in 2013 that liberated the windows and allowed them to be seen by all.

Associate Professor Keay and the Anderson Stuart Heritage Committee dream of adding another stained-glass window to the building and have a design from a contemporary artist ready to go. They need funding to make it happen. “We’d like to add something to the building that will become the heritage of the future,” he says.

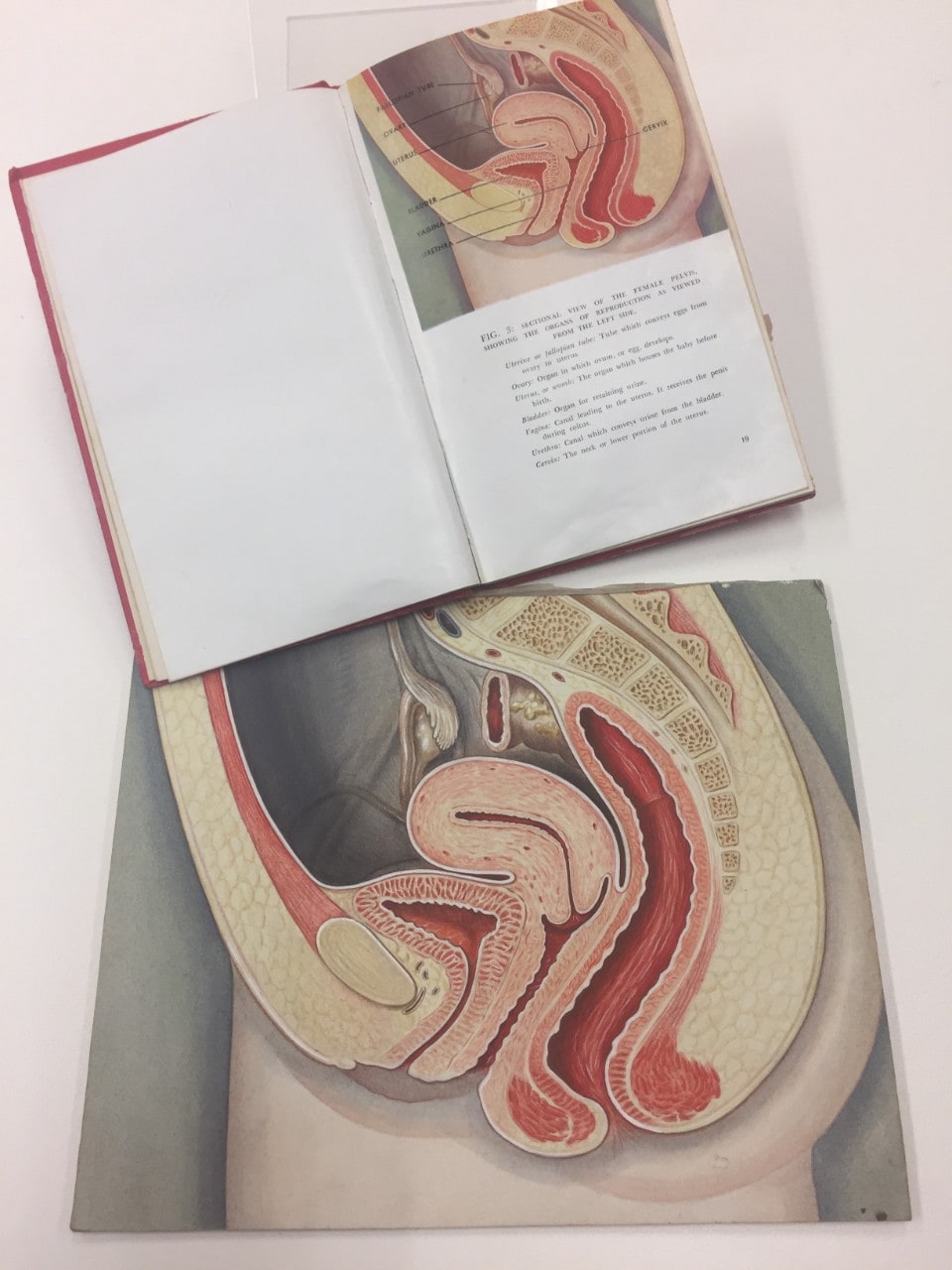

Vintage sex-ed illustrations

Photo: Catherine Storey

It might seem tame by today's standards, but when David Farrell’s Sex Education in Pictures was published in 1951, it would have been distinctly daring. Farrell, a medical illustrator in the department of anatomy in the 1940s and ’50s, wanted to impart sex education to young people “without any trace of emotional bias”. His slim textbook has fully illustrated chapters on everything from puberty to the sex organs. The Sydney Medical School Heritage Collection has a copy of the book, along with a selection of Farrell’s original drawings. The illustrations were discovered by the donor Jennifer White when going through the effects of her late father, Francis Buchhorn (MBBS '48).

A puffer fish helmet

Photo: Macleay Museum

For all its spikes, this helmet made from the skin of a puffer fish wouldn’t have offered much protection from the lethal taumangaria –weapons studded with shark teeth used by the i-Kiribati warriors of the South Pacific. It was acquired by Sydney-born conchologist, John Brazier, during an expedition in 1892. On the same trip, Brazier also acquired a much sturdier suit of armour made from coconut fibre and human hair. On his return to Australia, he gave both to the Macleay family, who later donated them to the University, along with the rest of their collection. The Macleay Museum’s Jude Philp says the helmet and armour were used in staged warfare. “It was part of a controlled and staged aggressive act, with attendants and aid-de-combats,” she says. “A way of solving problems and conflicts.”

Bark paintings almost 150 years old

Emu painting by an unknown artist (attributed to Iwaidja people), Essington Island, Coburg Peninsular, Western Arnhem Land, Northern Territory. Photo: Macleay Museum

This Aboriginal bark painting from Port Essington in the Northern Territory is almost 150 years old. That makes it one of the oldest bark paintings in Australia. It sits in the Macleay Museum collection with a number of others of a similar age from the same area. They were originally collected by conchologist and doctor James Cox in 1874 and were later donated to the University by the Macleay family. The paintings would once have decorated the interior walls of round winter dwellings and were likely used in storytelling and as records of people’s connections to land. These days they’re stored flat in humidity- and temperature-controlled drawers. They will go on display when the Chau Chak Wing Museum opens in 2019.