School for startups: the course launching new student businesses

PhD student Anastasia Volkova is the CEO and co-founder of FluroSat, a company that helps farmers grow more with less.

As a child, Anastasia Volkova dreamed she could fly. So far, so ordinary. But how many kids who imagine soaring through the skies make the next logical leap?

“I wanted to fly like a superwoman,” says Volkova. “Then I realised people used planes for that. So I decided I’d have to build planes.”

As it happens, Volkova did not grow up to build planes. But she is soaring nonetheless. The aeronautical engineer is completing her PhD in autonomous drone navigation at the University of Sydney. She is also the CEO and co-founder of FluroSat, a company that uses technology to help farmers grow crops more efficiently, using fewer resources.

An idea worth millions

It has been little more than a year since Volkova and four other University of Sydney students came up with the idea that would become FluroSat. The company now employs 12 people and has raised $1.5 million in investments and grants to develop its technology and expand into the United States.

While the technology is complex (hyperspectral cameras aboard drones and satellites plus sophisticated data analysis), the concept is simple: FluroSat spots problems with crops before the farmer can, and recommends how to fix them. Farmers and agronomists using the technology can intervene earlier and only where needed. This means less fertiliser and less water – and a more abundant harvest.

The course where big dreams meet business skills

FluroSat is one of several success stories to come out of the University’s Inventing the Future program, established in 2016 thanks to the Alexander Gosling Innovation and Commercialisation Fund. The gift of more than $300,000 from Dr Alexander Gosling AM, who has five decades’ experience in product development, has supported several programs at the University that aim to translate research into commercial success.

Inventing the Future brings postgraduate and research students from various faculties together to create commercially viable products to address some of the world’s most pressing problems.

The original FluroSat team (Anastasia Volkova, Xanthe Croot, Christopher Chan, Malcolm Ramsay and Brandon Cabanilla) united their expertise in experimental quantum computing, engineering, commerce, design computing and computational chemistry. Over 11 weeks, with support from lecturers in science, engineering, business and design, they created a prototype to fulfil their assigned brief: use nanosatellites to help remote communities.

People put a line between research and industry, but at FluroSat, half of what we do is research. We have to innovate every day.

Of the original group, only Volkova is still involved with FluroSat. But collaboration was crucial in shaping their ideas. Volkova’s knowledge of remote-sensing technology shifted the concept away from nanosatellites. Quantum physicist Croot recruited her father, a wheat farmer from country Victoria, to provide insights into how the technology could be used in agriculture.

As they spoke to farmers and agronomists about the idea, Volkova had a realisation. “People were not talking to us as a research group. Actual stakeholders were giving us real feedback on how they managed their properties. They were really interested. The point when you realise you’re onto something is when people start asking you how much it costs.”

While Volkova never imagined working in agriculture, she always wanted to do something practical. “As an engineer, I want to see things happen in the real world,” she says. “People put a line between research and industry, but at FluroSat, half of what we do is research. We have to innovate every day.”

That’s what Inventing the Future – and Dr Gosling’s fund – is all about. Associate Professor Maryanne Large, who initiated and coordinates the course, believes it is changing the way students think – encouraging innovation across disciplines and eroding traditional barriers between academic research and industry. “Teamwork is the biggest lesson,” she says. “The most successful teams really used all their different skills, and actively tried to bring in expertise when it was lacking.”

Business student Kimberly Bolton, plant pathologist Michelle Demers and chemist Jared Wood are tackling agricultural waste with their startup, BioChite.

A sustainable success story

When plant pathologist Michelle Demers enrolled in the course in 2017, she was interested in supplementing her science skills with some business knowledge. Now, she and her teammates – business student Kimberly Bolton and chemist Jared Wood – are transforming their project into a fledgling company, BioChite.

Their brief was to reduce the environmental impact of packaging. Research led them to a biodegradable plastic made from prawn shells and spider-silk protein – an invention from Harvard University’s Wyss Institute. There is much excitement worldwide about the product’s potential applications in medicine, from dissolvable sutures to coverings for burns and wounds.

But Demers had another idea. As a plant specialist, she wondered if biodegradable plastic could be used in agriculture. After a little reading, she learnt something exciting: the product was not only good for reducing plastic waste; it was good for plants and soils.

“It increases the soil’s organic content, increases soil water retention and protects plants against disease,” she says.

Wood got to work in the lab and created his own version, leaving out the spider silk and adding a few more plant-friendly components. Then Demers did some tests, adding Wood’s plastic to the soil of some seedlings.

“My results were amazing,” she says. “I stopped watering them and the plants with the plastic in the soil lasted almost two weeks longer than those without. I was blown away.”

Demers says BioChite could reduce agricultural waste by replacing the plastic sheets used to protect crops from temperature changes, control moisture in the soil and prevent weed growth.

It could also replace plastic seedling trays. Rather than tossing the packaging into the bin, gardeners would plant it in the earth, where it would biodegrade, nourishing the seedlings into the bargain.

The concept has won Demers and her teammates a place in the University’s Incubate program, which nurtures promising startups with expert advice. “I look at the statistics on startups and I’m realistic about the success rate, but even if we aren’t able to push it all the way, I’m still learning so much about business,” she says.

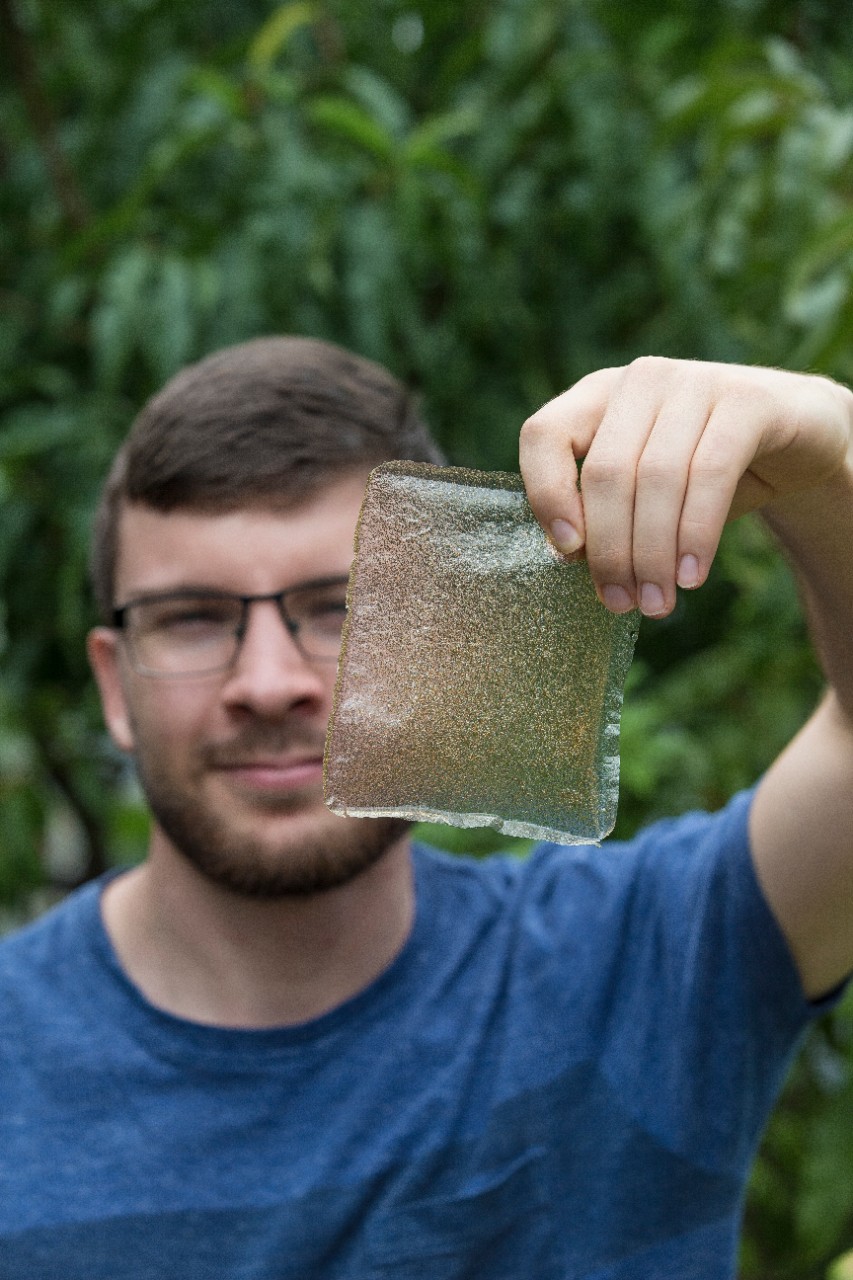

Chemist Jared Wood invented BioChite's biodegradable plastic in his lab.

The power of teamwork

Through Inventing the Future, Demers also learnt about the power of teamwork. Each member of the group brought something to the project: Demers’s agricultural knowledge, Wood’s chemistry expertise and Bolton’s business skills.

“In the normal course of events, I would never even have met these people,” Demers says. “But the best ideas come from a collaboration of different specialities.”

For Volkova, who began the program a year before Demers, things are starting to feel “very real”. She has $1.5 million to spend on her company’s development, and is preparing to launch her product in Australia and the United States. What next? “To take on the world,” she says.

She’s not joking. What she really wants is to change the way agriculture works so the world can feed and clothe itself sustainably.

“That’s our mission. I feel like there might be enough of us in this new era of technology who think the same way – who think big. It’s about shifting gears to make things work better for everyone.”