Mother's Day gifts in memory of three remarkable women

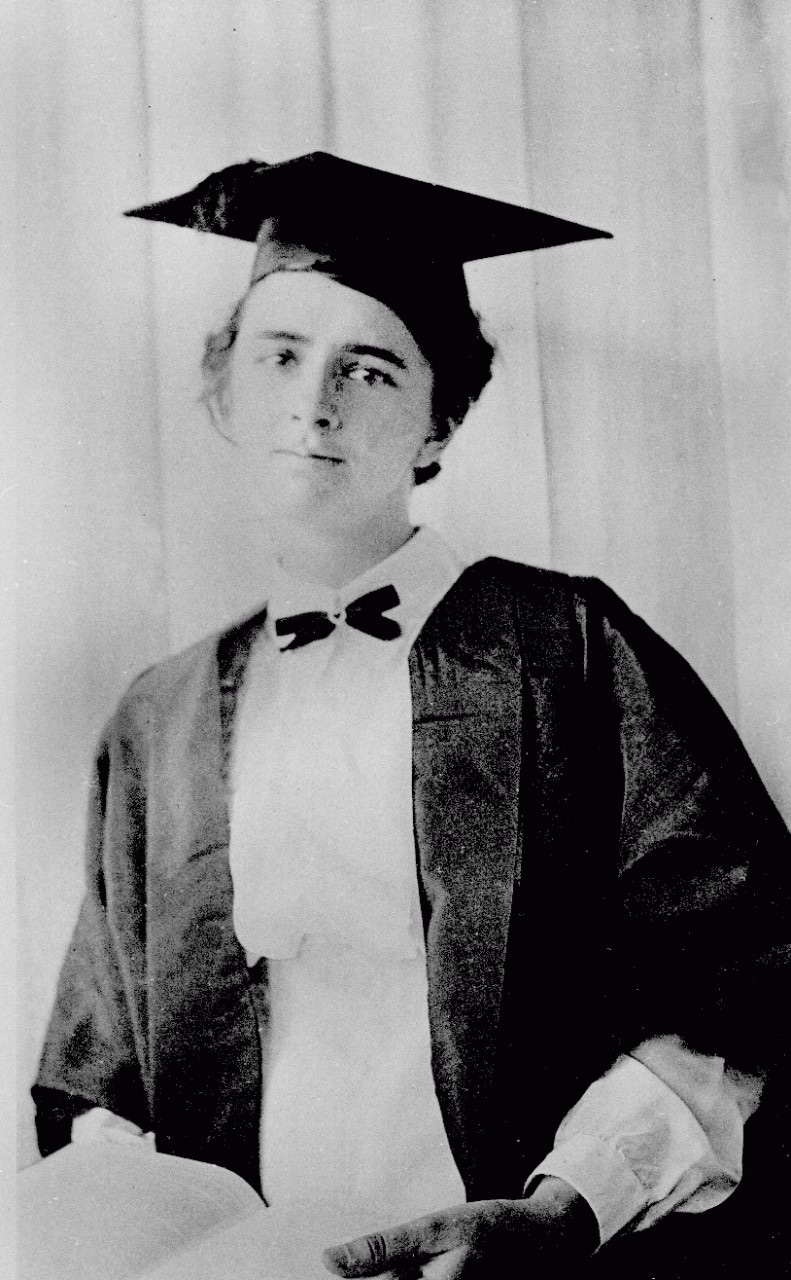

Edna Briggs was the University of Sydney's first female physics graduate.

First female physics graduate inspires daughters' scholarship

It was 1914 and Edna Briggs had just finished her first year at the University of Sydney. She went to talk to her physics professor about continuing in the subject. "Why don't you do geology?" he asked her. "That's a better subject for a woman."

When Edna demurred, he asked about her exam results. "I came first," she told him.

"Then," said the professor, "I don't suppose I can stop you."

More than a century on, Edna's daughters, Dr Barbara Briggs and Margaret Wright, are still drawing inspiration from their late mother - the first woman to graduate in physics from the University. Both daughters studied science at Sydney. Margaret was a physicist before switching to social work and Barbara is one of Australia's foremost botanists - the longest-serving female scientist at Sydney's Royal Botanic Garden.

Edna Briggs at her graduation in 1917.

When her daughters were children, Edna encouraged them to be curious about the world around them. They did chemistry experiments at home and, when they went out walking, she would tell them about the rocks they saw on the way.

Edna's legacy is set to inspire more young scientists, with Barbara and Margaret donating to the University to establish a scholarship for physics students in their mother's name.

Despite her talent, Edna's career was constricted by her society's expectations about women's lives. After graduation, with many of her male peers away serving in World War I, she secured a position as a demonstrator and researcher at the University, but the job ended with the war and the return of the servicemen. She later lectured in physics at the Sydney Teachers College and tutored at the Women's College. After marrying fellow physicist, Dr George Briggs, she supported him in his research. When World War II began, men were once again in short supply and Edna returned to work as a high-school science teacher.

"She would have loved to have had more of a scientific career," says Barbara.

"If this scholarship helps some student in their work, acknowledges their achievements and helps towards their future, then I'll be glad."

In memory of a mathematical mum

Elva Rae

Most of those who met Elva Rae during her life would never have guessed she was a brilliant mathematician. She was a minister's wife, a mother of five, a maker of handicrafts and sweets for church fetes.

But before her marriage, Elva had been a talented student, studying maths and chemistry at the University of Sydney. After she graduated in 1949, she spent several years working as a government biometrician for the Department of Agriculture, using statistics to improve crop yields.

She didn't talk much about her achievements, says her son, Peter Rae. "Mum was a fairly modest sort of person ... After she got married, she devoted herself to helping support Dad's career in the church, and to raising a family."

But whenever Peter and his siblings had difficult maths homework, their mother was on hand to help them work through problems at the kitchen table. "She was very patient and loving," says Peter. "Never one to lose her patience if you were slow to get it."

She also managed the family finances and did her husband's tax returns.

After his mother's death in 2012, Peter decided to make a gift to the University in her memory. His donation established the Mrs Elva Rae Talented Mathematics Students Initiative. The scholarship supports female mathematics students who qualify to participate in an advanced program to expand their studies.

"I was just missing mum and I decided I'd like to do something to remember her," Peter says. "I wanted to make sure her legacy was recognised and to honour her achievements."

A son's final gift supports brain research

Dr Christine Shaw

Dr Christine Shaw was in her early 60s when she started experiencing the tremors of Parkinson's. Dementia followed - as it often does in the advanced stages of the disease.

"It was horrifying," says her son, Paul Shaw. "This constant, slippery slide of losing that beautiful brain she had."

Throughout her life, Christine had been the kind of person who remembered everyone's name. After graduating from the University of Sydney in 1964, she worked as a GP and, later in her career, as an assistant surgeon. Paul remembers visiting her at work as a child during school holidays and hearing patients gush about her kindness.

"She was this wonderfully intelligent, gentle person," he says.

Christine died just after Mother's Day in 2014, at the age of 72, after a decade-long struggle with Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

To honour her memory, Paul is crowdfunding to raise $50,000 to support the Brain and Mind Centre's Forefront Healthy Brain Ageing Research Group, which aims to prevent or slow down the rate of cognitive decline in those at risk of developing dementia. The group's focus is on whether changes to sleep, diet, cognitive activity and other risk factors can reduce the underlying brain changes associated with the condition.

Paul sees his gift to the University not just as a contribution to research, but as a means of raising awareness about dementia in Australia.

"It's an excuse to talk to as many people as possible about protecting and preserving the brain," he says. "I wanted to do something mum would have been proud of."