New museum in Sydney: 12 must-see treasures that will be on show

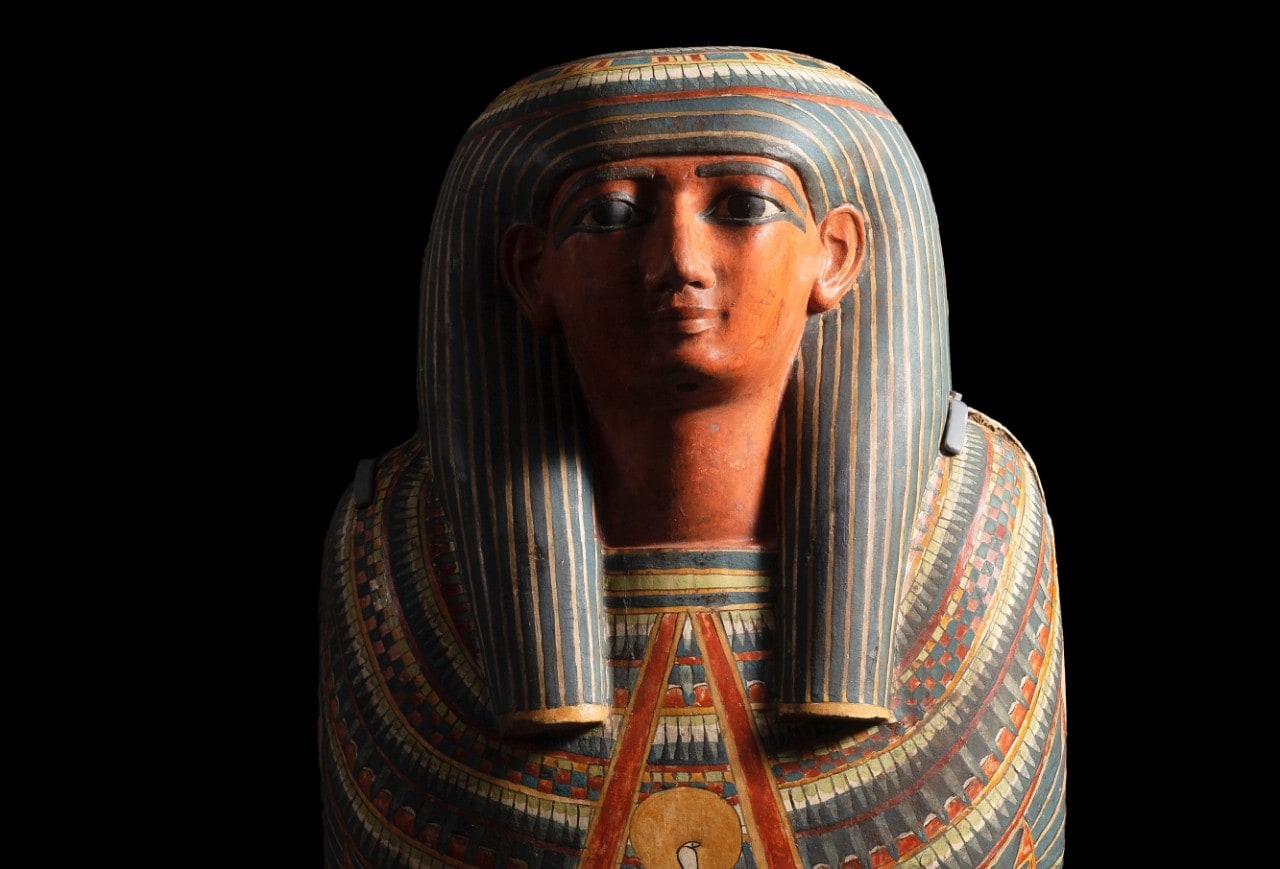

The Coffin of Padiashaikhet was donated by the University’s second chancellor, Sir Charles Nicholson. Record number: NMR.28.1-3

There are more than 450,000 treasures in the University’s museum collections, from ancient Egyptian mummies to masterpieces by famous artists. Until now, most of these have been hidden from view. In the University’s existing galleries, there is room to display just one percent of the collections’ objects.

That is set to change, thanks to $22 million in philanthropic gifts to establish the Chau Chak Wing Museum, currently rising from the ground on University Avenue. The new building – named for its major donor, Dr Chau Chak Wing – will have space to display double the number of objects.

The gifts from Dr Chau and fellow principal donors, Penelope Seidler, the Nelson Meers Foundation and the Ian Potter Foundation, continue a tradition of philanthropic support for the University’s museums. Many of the objects in the collections were donated. Here are some of the most fascinating gifts that will be on display when the new museum opens its doors.

Coffin of Padiashaikhet

The Nicholson Museum was founded in 1860 after Sir Charles Nicholson, the University’s second chancellor, donated his private collection of antiquities and curiosities.

Among the objects was a coffin complete with mummy, which he had bought from an antiquities dealer in Egypt. For more than 150 years, it was assumed that the mummy inside was Padiashaikhet – as identified on the coffin. More recently, radiocarbon dating has proved the mummy is an impostor. Tests date the coffin to about 700BC, while the mummy is 800 years younger. The seller had sliced off the mummy’s toes and knuckles to make it fit.

Statue of Hermes

This 2000-year-old marble statue, a donation from Sir Charles Nicholson’s UK-based sons in 1934, once sat by the duck pond at the Nicholson family home in Hertfordshire.

Its years outdoors have left it weathered but also kept it safe from the fire that burned down the house in 1899.

Mummified cat

When Margaret St Vincent Welch moved into care at the age of 91, her daughter Rosemary Beattie sorted through her mother’s possessions. Among them were 182 ancient Egyptian artefacts that had belonged to her grandfather, a former Sydney student who served as a First World War doctor in Egypt. Beattie donated the artefacts, including this mummified cat, to the University.

Despite the cat’s distinctively shaped ears, it could be a fake, albeit an ancient one. Mummies created to resemble animals were often bought by poorer Egyptians as budget offerings to the gods.

Peacock mosaic

Sir Charles Nicholson was a master of reinvention. After the English doctor arrived in Sydney in 1833, he became a businessman and politician. He went on to become the University’s provost and chancellor, and helped found the Nicholson Museum by donating his collection. But his greatest act of transformation had happened years before, when he shed the stain of his illegitimate birth by changing his name.

This mosaic – one of the items from his collection – has its own story of reinvention. Records indicated that Nicholson bought it in Sicily, but recently, a volunteer discovered its handwritten receipt, which proved it was actually a funerary mosaic from Rome.

“Museums are not static places,” says senior curator Dr Jamie Fraser. “We’re constantly learning new things.”

Etruscan mirror

This Etruscan mirror (c. 350 BC) shows Achilles killing Troilus at the Battle of Troy.

It was donated to the University by sisters Evelyn and Beatrice Tildesley, who studied at Cambridge before arriving in Sydney in 1913 and 1915 to teach at a girls’ school. Evelyn eventually became acting principal of the Women’s College.

Amphora

In Ancient Greece, this amphora was probably used to serve wine on social occasions. Senior curator Dr Jamie Fraser bought the piece over the phone at a London auction. He made the winning bid from Sydney, sitting on the couch, wearing his pyjamas. “England was playing in the soccer World Cup at the time, which I think helped lower the price,” he jokes.

The funds for the purchase came from the bequests of Mary Tancred and Shirley Joan Atkinson. They left money for the purchase in honour of Professor Alexander Cambitoglou, who curated the Nicholson Museum’s antiquities for 37 years.

Gold dinar coin

This gleaming coin was minted in Damascus during the Umayyad Caliphate, which spanned the sixth and seventh centuries AD. It was donated to the Nicholson Museum by Crown Prince Hassan of Jordan when he visited Australia in 1977. His gift was a symbol of the two nations’ close relationship, strengthened by the University’s archaeological digs in Jordan.

Omie barkcloth

The Omie people of Papua New Guinea create these cloths by pounding the inner layers of tree bark on rocks, then stretching them to form a canvas for richly evocative paintings. This barkcloth is one of more than 100 donated last year through the Commonwealth Government’s Cultural Gifts Program by Todd Barlin, the director of the Oceanic Arts Australia gallery in Paddington.

Power painting

One of the biggest bequests ever given to the University was worth a mighty $34 million in today’s money. It was left in the will of alumnus John Power, a doctor-turned-painter who became, says senior curator Dr Ann Stephen, Australia’s most important cubist.

“He’s little known today for several reasons,” says Stephen. “He was an expatriate; he did not need to sell his work; and almost all his artworks were given to the University by his wife, Edith Power. The new museum will finally allow his work to be seen.”

The University holds more than 1000 Power works, including the pictured Femme à l’ombrelle (1926).

Slide rule

One of the University’s first female doctoral students of architecture, Dr Valerie Havyatt, was a collector of precision drawing instruments and slide rules. She also worked with the University’s curator on the Macleay Museum’s collection of scientific instruments.

This slide rule was one of the items she donated in 2013. Its usefulness has been outdated by modern technology but its beauty is unquestionable.

Gold nugget

This nugget was donated in 1892 by Lady Susan Macleay, the daughter of the University’s then chancellor. Its 1851 discovery in Ophir, NSW, is thought to have started the first Australian gold rush. University staff unearthed and photographed it in 1955, after which it sank out of institutional memory until 1983, when it was found to have mysteriously changed shape – and lost three quarters of an ounce in weight.

Russian icon

Roddy Meagher was a NSW Supreme Court judge and an avid art collector.

On his death in 2011, he bequeathed his collection of paintings, drawings, sculptures, carpets, ceramics, furniture and archaeological artefacts to the University, where he had studied and taught.

He was a devout Catholic and his collection included 15 icons, including this 15th century example.