Tolling and price setting

- My starting position is that the toll review should be positioned to be able to transition to a network-wide solution as part of a longer-term commitment to ensuring road use efficiency, accompanied by some equity (justice and fairness) rules to ensure that no one is worse off financially.

- In discussing the tolls, we want to emphasise that we should set tolls at a level that delivers to users travel time savings benefits, given their value of travel time savings ($/person hour). We also recognise that the toll levels set are confounded by the need to raise revenue to fund the capital investment of a concessionaire (i.e., where tolls reflect the costs of, financing, constructing, designing, maintaining and operating the assets).

- This hybrid set of pricing rules does not make it easy to identify an efficient price since economics suggests that capital investment recuperation should be seen through the lens of other ways of repaying the investment debt rather than imposed on users (given society as a whole obtains a benefit). However, the PPP structure depends heavily of revenue from patronage forecasts. Errors in patronage forecasts have been the main source of errors in revenue (linked to optimism bias and statistical misrepresentation). Experience over many years has resulted in the business case for equity providers discounting patronage forecasts to 60% of the forecasts offered up by models and consultants. I attach two papers we have written based on what we suggest is the experience with PPPs, and while they do not explicitly discuss specific toll prices, they place the pricing issue into a relevant broader setting, linked in part to the allocation of risk.

- The current smorgasbord of toll settings in Sydney, set as part of a long-term concession for each tolled road, are adjusted based on an agreed indexation rule, which has created a distortion in the pricing of all roads, given the imposed baseline toll rate, which was often set politically. While the tolled infrastructure we have has been a net positive to users, the pricing of it has not helped the efficiency (and equity) of the entire network. We are stuck with it, with Transurban effectively controlling the Sydney Road network under current contracts.

- At a previous parliamentary inquiry where I spoke, we got nowhere with new ideas, and the committee recommended staying with the existing pricing model under the concession agreements. To reproduce what I said, given the analysis undertaken in Hensher and Mulley (2014), we identified for all roads, a 5c/km distance-based charge (DBC) in peak periods only plus halving of registration fees 1, which made almost no user financially worse off and a slight gain to Treasury revenue, while close to a 6% improvement in peak hour traffic (approximately returning the busy periods to school holiday traffic levels in many locations):

"Once buy in is secured and travel time savings demonstrated, the distance-based charge can be increased. For example if we increased it by 1c/km (to 6c/km) in the peak, this results in additional revenue of $4.2bn per annum, more than enough to remove the tolls on existing tolled routes and compensate the toll road operators over the duration of the concession, with part of the distance-based revenue raised on the tolled routes (and additional funding if required, although this is unlikely)." Drawn from Hensher, D. A. & Mulley, C. (2014) Complementing distance-based charges with discounted registration fees in the reform of road user charges: the impact for motorists and government revenue. Transportation, 41 Number, 697–715.

- Hence, my suggestion is a toll road repricing model that will move seamlessly, in the future, into a network wide solution. I like the idea of a peak, shoulder, off-peak distance-based charges that can be capped.

- The DBC should vary by distance bands (and not arbitrary spatial zones), and I support some justice and fairness criteria to compensate those who are financially worse off, or adjust the amount outlaid (like a user side subsidy instead of a provider side subsidy).

- The suggestion of an access charge is, in network terms, like a registration fee, to give access rights to the road network. We already have a discounted system for registration fees when the amount spent on tolls exceeds a stipulated sum. Instead of offering a discount on registration linked to toll outlays, I support converting this to an access charge (ultimately for all roads) that is used to cover the net costs of toll road operators when annual kms exceed an agreed quantum.

- One also needs to distinguish discounts and/or caps according to who pays for the tolls, such as households or businesses, an issue that may be problematic when we have household-business registered vs other non-household business registered vehicles. This is an important issue in the context of equity (justice and fairness).

- A question of great importance will be in setting a DBC that achieves multiple objectives, notably reflecting an efficiency outcome (distorted if only applied to tolled roads, but which can be resolved in time through a network-wide re-pricing), an equity outcome, and an outcome that accommodates the debt-repayment (and RoI) model of the toll road service provider (i.e., Transurban).

- In recognising this, a starting position might be to identify the revenue per annum from tolls, the net debt recovery required per annum plus the acceptable profit margin (given risk profile) and the total annual kilometres of all vehicles (cars and trucks). This can be used to calculate a starting estimate of a crude average DBC:

- (Total revenue minus net debt recovery and other annual expenses)/total annual kilometres

- The resulting average can be increased for trucks and decreased for cars given the modal shares, to arrive at the same aggregate average DBC.

- The next challenge is to identify the trip length distribution (ideally with actual number of trips by mode) and to tailor the DBC to vary by kilometres driven, possibly blocks of 5 km. to ensure an average DBC aligned with the funding objectives. One assumes such data is with Transurban, and even TfNSW?

- I attach a PDF of a slide presentation of what a network-wide road pricing reform model should consider, and a proposal to undertake a trial to test the ideas.

- A serious challenge is the ability to remove fuel excise, which is collected Federally and have it replaced by a DBC, the latter one assumes will be collected by a state-based agency. Initially I assume the fuel excise with stay in place.

- There will be complications as we transition to electric cars that will not pay the fossil-fuel excise, and my view is that a DBC should be aligned with travel time savings and not with the energy source of the vehicle. The latter might explicitly be a charge linked to emissions and it might be possible to combine into a DBC with a lower rate for lower emission cars (noting at present that there are still 30% emissions beyond the tailpipe of electric cars).

See details in https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/handle/2123/30276/ITLS-WP-23-06.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- I offer some elasticities (Table 1) of the relationship between toll levels and traffic responses which may be useful for someone testing variations in tolls under a DBC and its link to changes in traffic levels and revenue.

Table 1 Elasticity of traffic level with respect to tolled routes

Wuestefeld and Regan (1981)

Roads between -0.03 and -0.31

Bridges between -0.15 and -0.31

Average value -0.21Sixteen tolled infrastructures in the US (roads, bridges and tunnels)

White (1984), quoted in Oum et al. (1992)

Peak-hours between -0.21 and -0.36 Off-peak hours between -0.14 and - 0.29

Bridge in Southampton, UK.

Goodwin ( 1988), quoted in May (1992)

Average value -0.45

Literature review of a number of previous studies

Ribas, Raymond and Matas

(1988)Between -0.15 and -0.48

Three intercity motorways in

SpainJones and Hervik (1992)

Oslo -0.22

Alesund -0.45Toll ring schemes, Norway.

Harvey (1994)

Bridges between -0.05 and -0.15 Roads-0.10

Golden Gate Bridge, San Francisco Bay Bridge and Everett Turnpike in New Hampshire, US.

Hirschman, McNight, Pucher, Paaswell and Berechrnan (1995)

Between -0.09 and -0.50

Average value -0.25 (only significant

values quoted)Six bridges and two tunnels in New York City area, US.

Mauchan and Bonsall (1995)

Whole motorway network -0.40 Intercity motorways -0.25

Simulation model of motorway charging in West Yorkshire, UK

Gifford and Talkington (1996)

Own-elasticity of Friday-Saturday traffic -0.18

Cross-elasticity of Monday-Thursday traffic with respect to Friday toll

-0.09Golden Gate Bridge, San Francisco, US.

INRETS (1997), quoted in TRACE (1998)

Between -0.22 and -0.35

French motorways for trips

longer than 100 kilometres

UTM (2000)

-0.20

New Jersey Turnpike, US.

Burris, Cain (2001)

and

Pendyala

Off-peak period elasticity with respect to off-peak toll discount between

-0.03 and -0.36Lee County, Florida, US.

- Potential Price Plans, aligned with Mobility as a Service (MaaS), that might be worth considering within a DBC reform structure:

Casual off-peak (rare peak use)

Modest off-peak discount and peak surcharge

Frequent off-peak

Fixed monthly fee, free in off-peak, standard rate in peak

Frequent peak

Higher fixed monthly fee, free in off-peak, discounted rate in peak

Long-term committed / risk averse

Guaranteed toll rates over 10+ years (protect against price rises) for "customer investors" in "Warratah" bonds or toll-road equity.

- Discounted tolls could be in place of dividends (investment risk reduced as the return is controlled by the customer's toll-road usage).

- Investment could be via super funds (i.e., redirection of individuals' existing funds rather than requiring additional household investment).

Finally, some generic rules of good practice are offered. Schemes can be both economically viable for investors and politically actionable in the face of voter expectations if these general principles are adhered to:

- There ultimately needs to be one mobility revenue scheme (or a fully interoperable series of schemes) for a region / province / conurbation that allows each resident access to all modes. With support from the OEMs and standards organisations like IEEE and SAE it is possible that through connected vehicles and apps universal mobility charging (PAYG) might even be achieved much as most mobile phones can now roam worldwide

- All of the proceeds from the scheme need to go back into the transport network also across all modes, not just (as I suggest is often the case) back into roads, and definitely not back into the general treasury. A key component must that they must fund alternative mobility enhancements as a priority, effectively imposing both a "carrot" and a "stick" to get drivers out of personal vehicles.

- Incentives need to be created for driving at certain routes or times that mitigate congestion including secondary / tertiary road usage or driving at nonpeak times.

- Petrol taxes per se need to be eliminated, however incentives for LEV and ZEV usage and disincentives for ICE use can be provided selectively by a carbon tax or other environmental assessment. A question of semantics perhaps but politically very important.

Extra from Hensher et al. (2016)

Hensher, D.A., Ho, C. and Liu, W. (2016) How much is too much for tolled road users: toll saturation and the implications for car commuter value of travel time savings? Transportation Research Part A, 94, 604-21. (This paper has generated extensive media interest – newspapers, radio and TV).

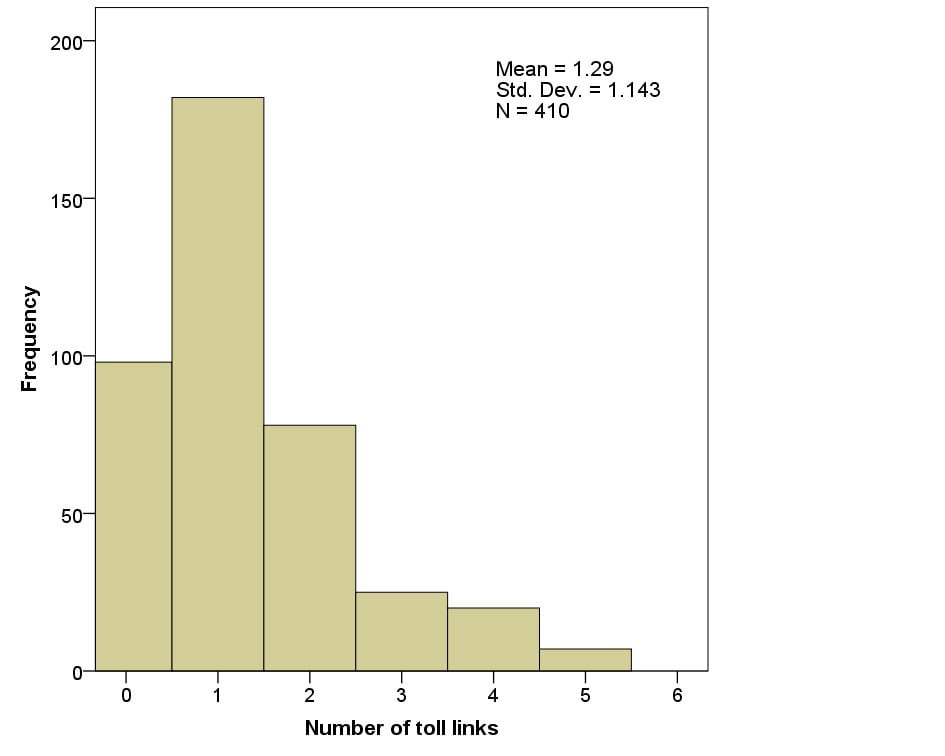

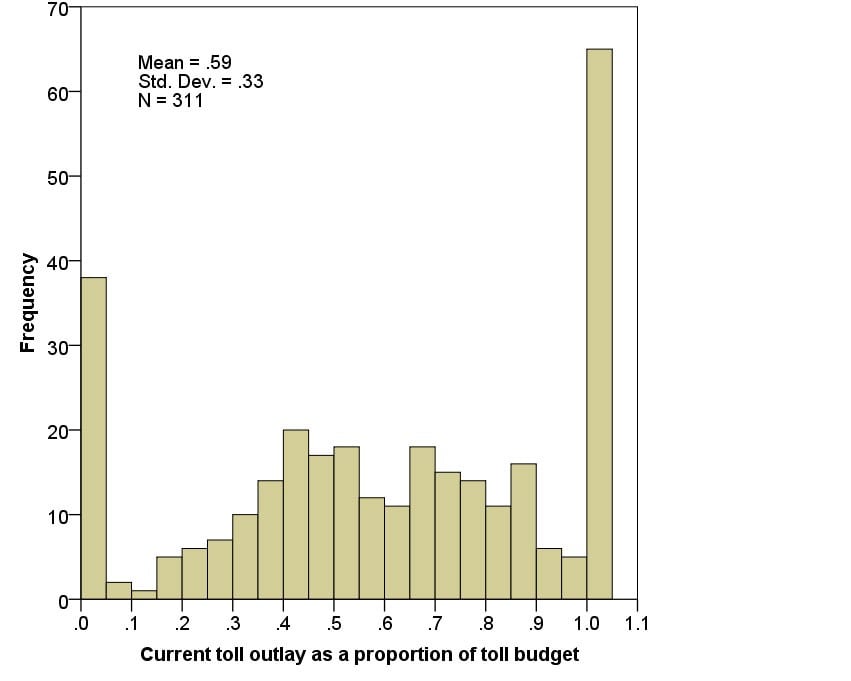

Figure 6 shows the number of toll roads used for the journey to work (JTW) of the sampled workers. The Journey from work (JFW) is very similar. Of the commuters whose travel involved toll roads, the majority use one toll link with the most popular toll roads being the M5, followed by the SHB, M7, M2 and the Eastern Distributor (ED). However, it is not uncommon for the JTW to involve more than one tolled link. The most popular combination of toll roads are the M5 and M7 ($4,723 per annum), the SHB and LCT ($2,462 per annum), the ED and CCT ($4,046 per annum), M7 and M2 ($6,739 per annum), and SHB, LCT and M2 ($5,539 per annum) with the number in parentheses being the annual toll outlay on commuting, assuming a 5-day working week and a 48-week working year (4 weeks vacation). The sample average annual gross personal income is $93,000 per annum (Table 2), which after tax is around $68,000. The range of toll outlays associated with the toll activity summarised above are from 2 to 9 percent of the after-tax income for toll users (although there are a number of users in excess of 9 percent). As indicated, the toll outlay for toll road commuters is substantial, and an addition of more tolled links may result in an increasing number of commuters not prepared to pay tolls to save travel time. Figure 7 shows the current level of toll saturation amongst toll road commuters. One in five toll road commuters (65 out of 311 workers) have reached their saturation point, with an average level of toll saturation amongst toll road commuters around 60 percent. Thus, some commuters can still sustain increasing toll costs; but a substantial proportion appear to be no longer prepared 'to pay to save'.

Figure 6. Number of toll roads involved on journey to work

Figure 7. Current level of toll saturation amongst toll roads commuters

On average, the JTW or JFW of a sampled car commuter takes close to an hour, with one-third of the commuting time being on toll roads . Over the last two weeks, commuters have outlaid, on average, $50 on toll roads with the maximum amount of toll outlay of $374. The toll outlay is currently smaller than the budget commuters have for commuting on toll roads, with an average gap between toll outlay and toll budget of $37 ($87 – $50 = $37) for 2-week commuting or $3.70 per day if commuters travel to and from work five days per week. The average age of sampled workers is 43 years and a vast majority (80%) work fulltime. Five percent of the workers have their commuting tolls covered by employers, and another 4% of workers pay commuting tolls through their own business. In terms of gender and occupation, the sampled workers spread quite evenly across both sexes and cover all occupations.

Footnotes

Excluding Stamp duty and other charges such as vehicle transfer administration fees (paid on change of ownership) and number plate fees (paid on first vehicle registration).

A number of commuters live in the Central Coast, which is over 90 kilometres from the CBD. In addition, commuters coming from the far Outer West spent significant time on connected toll roads (i.e., M7, M2, Lane Cove Tunnel and Harbour Bridge).