Funnelling congestion: How Sydney exacerbated congestion after spending tens of billions on transport infrastructure

The opening of Sydney’s much awaited $3.9 billion Rozelle Interchange in November 2023 was met with gridlock. Changes made to existing surface roads to make space for four dedicated tolled lanes connected to the new WestConnex motorway disrupted existing traffic flows onto the Anzac Bridge (Wiggins, 2023). Whilst the motorway was meant to improve traffic flow on the already busy Victoria Road, the substantial reduction in lanes associated with the new interchange has significantly slowed traffic. Emergency works undertaken to add an additional lane where the City West Link joins the new Crescent Overpass will shift rather than address the bottleneck (Stonehouse, 2023). The government has limited options for unravelling the mess as any changes which disrupt the flow of traffic onto WestConnex would require negotiation with the Transurban consortium.

How do such missteps with transport infrastructure occur? Why would a government fund expensive urban motorway infrastructure that will channel even more traffic into a congested central area? The answer rests with poor governance and an inability to assess projects at a city-wide network level. Despite its cost and purported importance, Rozelle Interchange was not reviewed by Infrastructure Australia during the project’s later stages nor were detailed designs shown to local councils and communities. Regrettably, this is not an isolated case. The desire to rush through projects with poor cost-benefit was observed with the decision to build the $9 billion Western Sydney Airport Metro line, which Infrastructure Australia advised against (Rabe and O’Sullivan, 2021). Then there was the signing of multi-billion-dollar tunnel boring contracts for Metro West shortly before the March 2023 NSW state election (Sydney Metro, 2022).

An even bigger mess for rail

Over $50 billion has been committed to automated metro railways in Sydney yet both initial schemes have managed to increase congestion on Sydney’s busiest Western rail line in their endeavour to increase capacity elsewhere.

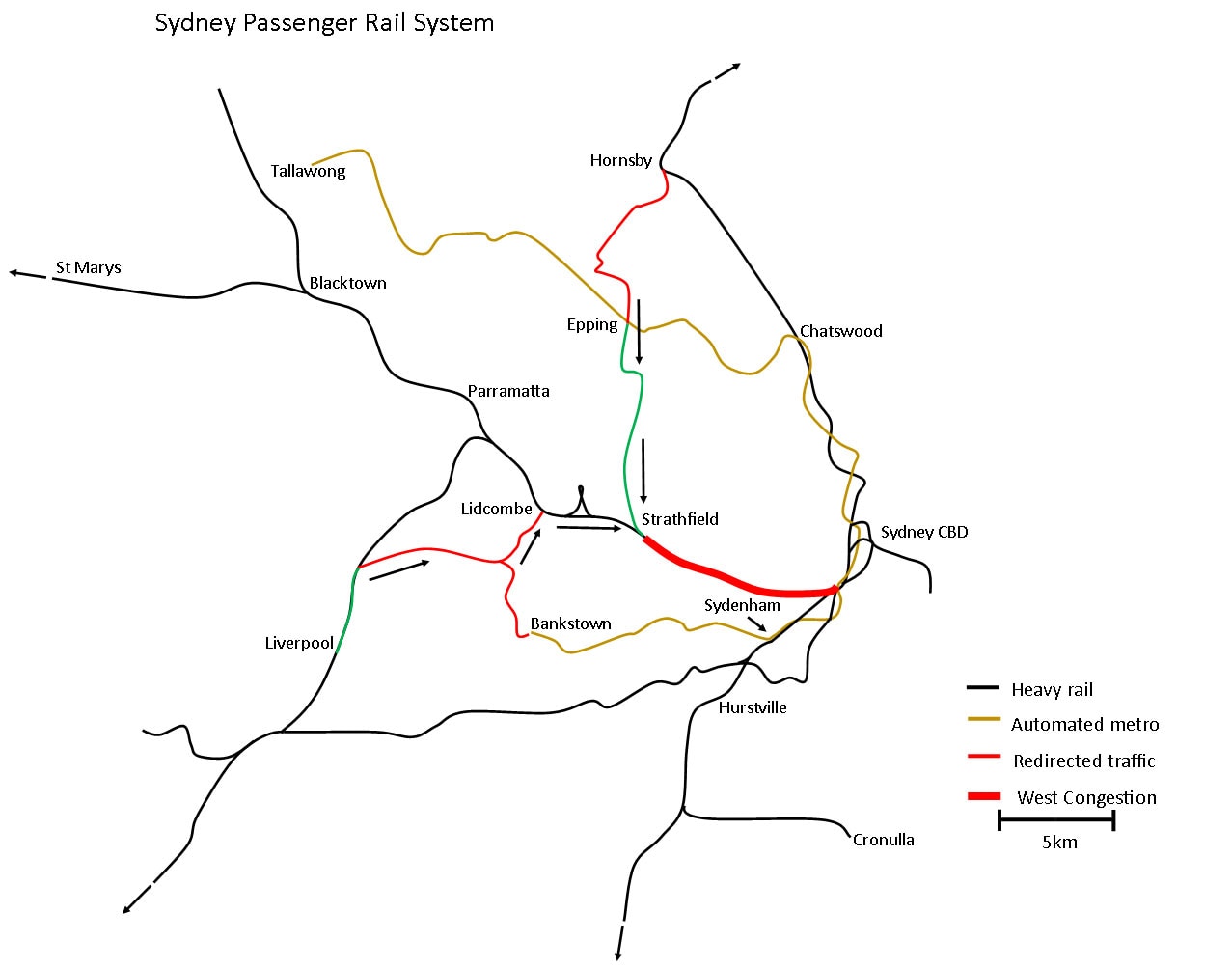

Sydney’s first metro connected the Northwest sector to the existing heavy rail network at Chatswood. Whilst the line west of Epping was new, the metro cannibalised the relatively new heavy rail Epping-Chatswood link which opened in 2009. Aside from the disruption caused by closing the line for over a year, whilst metro conversion works were undertaken, the metro unwound congestion relief provided by the Epping-Chatswood rail link. It did this by forcing Hornby services, previously diverted by the Epping to Chatswood link to the North Shore Line, back onto the route via Strathfield and the congested Western Line into the CBD (See Figure 1).

To make matters worse, Phase 2 of the metro, from Chatswood through the Sydney CBD and onto Bankstown, required an expensive conversion of the existing heavy rail line from Sydenham to Bankstown. Leaving the prohibitive cost of this exercise aside (Day and Merkert, 2022), closure of the Bankstown Line to heavy rail requires traffic from Liverpool and stations west of Bankstown to be redirected onto the already congested Western Line at Lidcombe. This will result in significantly slower and less reliable train services from these already poorly served parts of the City (Day and Day, 2023).

In contrast, Sydney’s second major metro project, Metro West, which connects the CBD to Parramatta, appears superficially to add much needed capacity to the congested western rail corridor. Connecting Sydney’s two CBDs seems a no brainer. Regrettably, Metro West will fail to alleviate Western Line congestion. The overwhelming majority of passengers travelling on the line originate from destinations west of Parramatta. These passengers will not change onto the metro at either Westmead or Parramatta as the existing railway offers both higher frequencies (every 3 minutes instead of 4) and a choice of three CBD station destinations as opposed to just the one on the new metro line. The existing Western Line also offers compatible journey times, better interchange opportunities and through services to destinations on the North Shore. This realisation, coupled with the need to get some utilisation from this $26 billion metro, is behind the recently introduced imperative to rezone land for very high densities along the new metro route and pivot away from the narrative that Metro West provides congestion relief to the existing rail system (Hyland, Roe and Lewis, 2023).

How can Sydney get it so wrong?

In a nutshell, successive NSW governments have steadfastly refused to develop and implement a meaningful long-term strategic transport and land-use strategy. This is not simply an oversight. Students of Lynn and Jay’s weighty tome “Yes Minister” will recall the horror with which Minister Hacker’s Permanent Secretary (in those far off days when permanent departmental heads were actually permanent!) heard the news that his Minister had been lured into accepting the role of transport supremo. As Sir Humphrey observed,” we need a transport policy like an aperture in the cranial cavity.” He went on to describe the job as a bed of nails, a crown of thorns, and a booby trap (Lynn and Jay, 1989, p429).

The reasoning behind Sir Humphrey’s concerns, unfortunately, remains apposite in a parliamentary democracy. A meaningful transport and land use strategy will attract opposition from all quarters. It would raise questions about why we would want a very high density multi story Asian style city that needs metro railways with a standing capacity up to about 50,000 passengers per hour in each direction. Why would we not put such high densities along the Northern Beaches where the amenity would be much higher than the Bankstown corridor? In addition to contemplating the redevelopment of Rosehill racecourse, why don’t we convert Centennial Park and the Randwick racecourse to high density apartments in order to give the Metro West fiasco at least some patronage from the east into the multibillion-dollar Wynyard Station redevelopment? After all, the future projected route to Kogarah with a leg to La Perouse will hardly generate sufficient demand to justify a metro without the massive redevelopment we dare not talk about!

In a titular sense the NSW Department of Transport has bought all transport undertakings into a single entity, in the process emasculating the professional knowledge previously held by the separate entities. However, the Department has studiously avoided any attempt at joining up the dots. Instead, billions of dollars have been spent on a variety of new builds that have paid insufficient attention to network and land use dynamics. Conversely, they have enriched the consultancy industry, major construction and transport operating companies and the innumerable bankers and lawyers entrusted with managing the sea of required and opaque contractual obligations. Inevitably, it has been a case of locking in the building commitment first and revealing the societal implications and real costs later.

It did not have to be so. There was no demand driven imperative for such haste in selecting a plethora of new and incompatible technologies. There is no thoughtful explanation on why the link between Parramatta and Westmead, already served by numerous direct bus services and a minimum of six train services per hour in the off-peak period, also requires a highly circuitous and expensive light rail connection and an additional metro railway!

The unfortunate result of this plethora of suspect decision making is missed opportunities and ineffectual investment which has assisted in overheating the construction industry. At the macro level, central area employment has taken a significant hit globally in the aftermath of the covid pandemic which served to exacerbate what was already an increased tendency to work from home. Additional automation and AI technologies will continue to challenge the traditional office centric role of the CBD. In light of this, the much-vaunted new Chatswood to Sydenham metro will be more than enough to take care of any possible increase in CBD peak hour commuter demand for the foreseeable future. Yet not only has the NSW government committed to what amounts to open-ended expenditure on an additional metro from Parramatta to the City Centre, but also completed a major tollway upgrade designed to encourage more cars to try and enter Sydney’s highly congested area. In contrast the poorly serviced Victoria Road/Ryde corridor has been adversely impacted as has travel to the Sydney City Centre from the Liverpool area.

Where to next?

No politician has an appetite for courageous policy decisions regarding the future size and configuration of the Sydney metropolitan area. Yet even they are becoming forcibly aware that the excesses of the last few years are creating a nest of problems that cannot readily be rectified and are going to cause increasing acrimony amongst many constituencies. Discerning politicians have long appreciated the role of a suitable scapegoat responsible for pointing out electorally unpleasant truths. Traditionally, Government Treasuries have often fulfilled the important role of investment appraisal by questioning expenditure on everything. Unfortunately, this function has lapsed. Given the extent of public debt and the ever-increasing calls on the public purse a renewed vigour from this quarter might be acceptable.

It is probably too much to hope that Universities can devote greater resources to pressing real world policy issues. However, given the suppression of independent thought within government departments, is there any hope for better funding of independent research institutes? Referral of an issue for further investigation has the immediate political advantage of deferring commitment whilst giving at least the appearance of positive action. Such an apparently open-minded approach might even permit the adoption of a subsequent recommendation based on thoughtful and integrated analysis rather than on an immediate need to pacify a lobby group or particular ideological prejudice. Might a meaningful approach to land use and transport planning emerge from an independently funded research institution?

References

Day, C.J. & Day, R.A. (2023). Taken for a ride: How the poor cost-effectiveness of Sydney’s automated Metro Railways provides a salutary lesson for infrastructure planning. ITLS Working Paper, 22-23.

Day, C.J. & Merkert, R. (2022). Costs of Sydney’s driverless train conversion outweigh the benefits. The Conversation, 16 August.

Hyland, J., Roe, I. & Lewis, A. (2023). NSW Government plans to see Rosehill Racecourse replaced by more than 25,000 homes as Metro West confirmed. ABC News, 6 December.

Lynn, J. & Jay, A. (1989). The Complete Yes Minister. BBC Books, London.

Rabe, T. & O’Sullivan, M. (2021). Cost far outweighs benefit: Sydney’s $11b airport rail link slammed. The Sydney Morning Herald. 12 March.

Stonehouse, G. (2023). Construction on Sydney's West Link and Anzac Bridge to prevent bottlenecks around Rozelle Interchange. ABC News, 4 December.

Sydney Metro. (2022). Final major tunnelling contract awarded for Sydney Metro West.

Wiggins, J. (2023). Rozelle road designs kept from public view. The Australian Financial Review, 15 December.

Related articles

Electric Cars – They will in time increase car use without effective road pricing reform