At the heart of dementia

Finding a treatment for dementia is an international priority. Protein plaque in the brain is the main focus, but Professor Jonathan Stone believes plaque is just a side effect of other events caused by the beating of the heart.

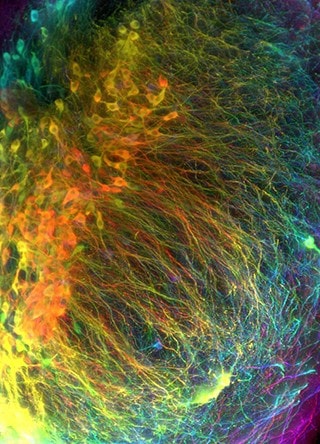

The substantia nigra, where motor problems can originate

Professor Jonathan Stone (BSc Med ’63 PhD Med ’66 DSc ’77) talks in a quiet and thoughtful way, but his ideas are attention grabbing.

The implications of his research into the causes of dementia aren’t just medical, they’re existential as they draw an unlikely culprit into the light.

For Stone and his colleagues, the evidence points to dementia being caused by the beating of the human heart.

“Many workers in the field still at least hope that dementia is caused by something you can design a drug against, something you can face square on and overcome,” Stone says. “The idea that it’s caused by the beating of the heart - that takes us somewhere else completely.”

The heart is heavy with symbolism, representing love, nurture, courage and, indeed, life. But Stone’s research suggests even a healthy heart can be the enemy of life as it pummels the delicate architecture of the brain with a relentless pulse. The brain is particularly susceptible to this pulse-induced damage because every part of it must be richly supplied with blood so it can do its work. This means blood must penetrate into the brain’s furthest recesses with the least resistance possible.

“For most people, across most of their lives, this works beautifully with only minimal damage,” says Stone. “What protects the brain in younger people is a brilliant piece of evolved engineering in the aorta.”

The aorta is the largest artery, taking blood to every part of the body, but it has another talent. The aortic tissue contains elastin that, as the name suggests, allows it to expand by about 15 percent with every pulse, thereby absorbing some of the pulse’s energy. It’s a buffer that protects the fine capillaries of the brain.

But with age, some dangerous changes get under way. “As a person gets older, the aorta begins to lose its vital elasticity,” says Stone. “It follows that the blood pressure goes up, the pulse becomes more intense and it starts to destroy the capillaries.”

When capillaries are damaged, plaques begin to form. As the damage accumulates, symptoms appear and the terrible consequences of dementia assert themselves. This is all based on a completely natural part of the ageing process, so the implication of Stone’s work is that a long life makes dementia not a disease but an inevitability.

Right now, dementia is the second largest killer of people in Australia, behind heart disease. About 330,000 people currently have dementia, with 1.2 million more people involved in caring for them.

Professor Stone

By 2050, it is estimated 900,000 people will have dementia. The burden this will place on the community is hard to contemplate.

Not everyone agrees with Stone’s view of the evidence. Most research and indeed funding for dementia currently goes to projects that focus on protein plaques that form in the ageing brain, each damaging a patch of tissue.

“The work on the protein theory is elegant and powerful,” Stone says. “But it’s only part of the story. Our evidence indicates that plaques form around the sites of the damage that the pulse is causing to the capillaries.”

For Stone, the protein theory struggles to answer two questions. Why do the plaques appear scattered throughout the brain? And why do the plaques appear in old age? Professor Stone believes his theory answers both questions.

He views it as significant that improving cardiovascular health, and lowering blood pressure through exercise, weight loss and medication, also delays dementia.

The thinking that brought Stone to this line of research began for him at the University of Sydney in the early 1990s. Along the way, his work was advanced by the insights of colleagues, including Dr Karen Cullen (Anatomy) who showed that plaque formed around small blood vessels, and Professor Michael O’Rourke (previously a physiology student, now a program leader at the Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute), who discovered how and why the pulse increases its intensity with age.

Most recently, Stone’s research has benefited from a team of gifted University of Sydney researchers from anatomy, physiology and medicine.

What protects the brain in younger people is a brilliant piece of evolved engineering in the aorta.

Dementia researchers are always wary of discussing the idea of a cure. Unlike other parts of the body where damaged cells are routinely replaced, the brain does very little in the way of self-healing. But a recent breakthrough offers hope.

Researchers at the University of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre used a dog’s own stem cells to cure it of Canine Cognitive Dysfunction, a condition very similar to human dementia.

This is a game-changer for dementia researchers and the project leader, Associate Professor Michael Valenzuela, of the University’s Brain and Mind Centre, sees the implications.

“We used to think that we didn’t have the capacity to grow new brain cells,” Valenzuela says. “But we now know that’s not true. We hope we can turbocharge the natural process of neuro-regeneration by transplanting customised cells.”

These results have Stone exploring new questions. “We need to know whether the stem cells are repairing the brain circuitry itself, or perhaps its blood vessels. This is a striking observation that deserves thorough exploration.”

Stone is also thinking of ways forward with dementia by pursuing another line of research that he calls “acquired resilience”. His team is investigating a hidden mechanism of resilience in the human body that is somehow triggered by a diverse array of interventions including plant toxins, red light, exercise - and saffron.

“Understanding this mechanism could radically change current treatment regimens for dementia and a number of other conditions,” he says.

As he makes his way to his office on the upper floors of the University of Sydney’s historic Anderson Stuart building, Stone passes through its grand Victorian hallways.

These hallways were once crammed with makeshift offices that obscured the building’s magnificent stained-glass windows. Stone has been a key player in opening up these spaces and letting in the light. Many believe his work on dementia is doing much the same thing.

Written by George Dodd

Photography by Victoria Baldwin (BA ’14)