Natural disasters affect some of the most disadvantaged

Australian-first research has identified a disaster hotspot where many disadvantaged communities are located, indicating socio-economic status can determine whether hazards become disasters - but urban areas are not immune.

If we don't deal with inequality... no amount of spending will stem the ever-increasing disaster losses.

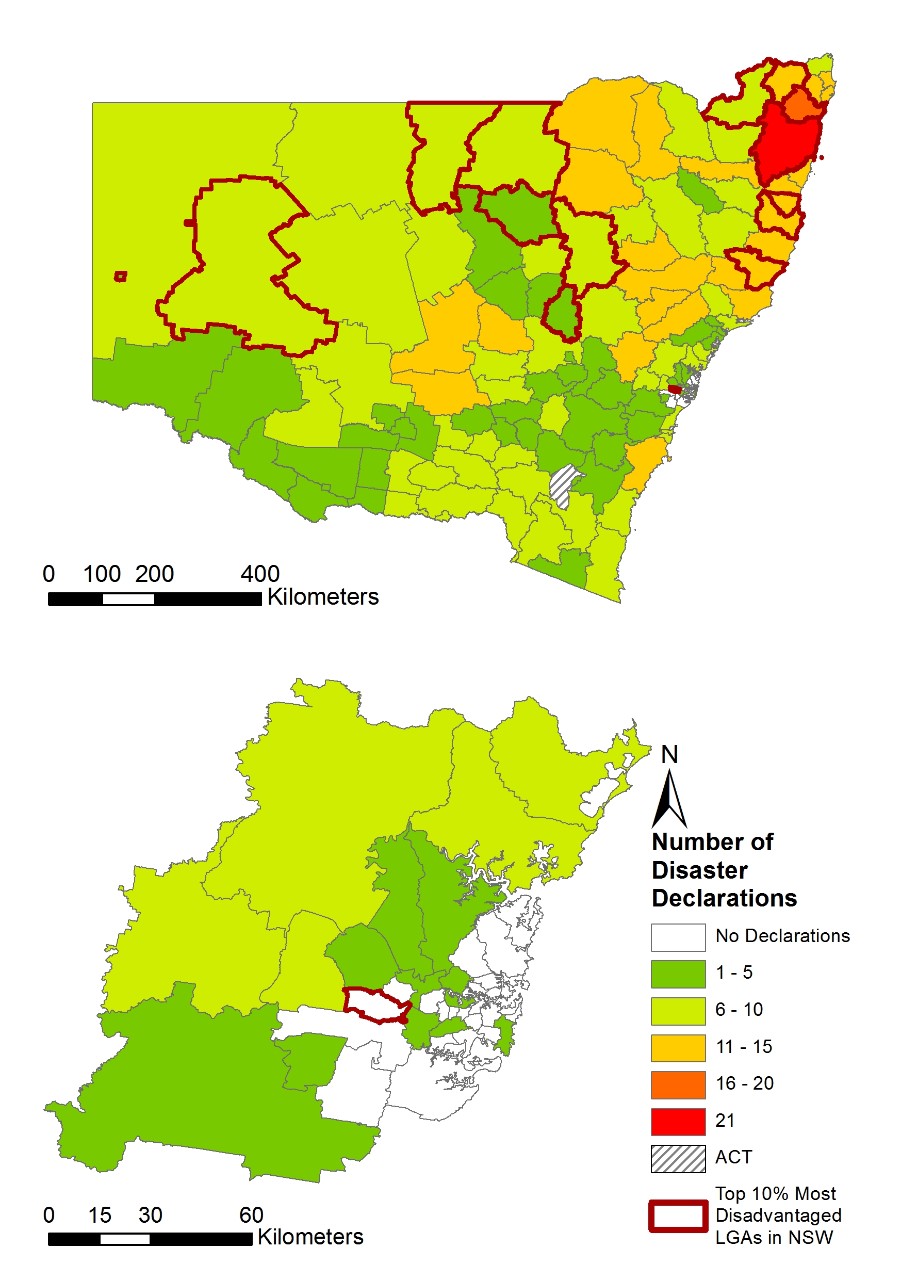

Map of the number of times an LGA was affected by a natural disaster declaration of any type. Lower map is the Greater Metropolitan Region of Sydney. LGAs highlighted with a thick red boundary represent the top 10 percent most disadvantaged LGAs. Top of page: Lake Repulse in Tasmania. Source of photo: flickr.com/photos/the_smileyfish/8348629576/

Disasters are a regular part of life for communities across the globe. Already this year, disasters have cost US$71 billion and claimed some six thousand lives.

Australia has a long history of natural disasters, from catastrophic bushfires to flooding rains.

Many people are asking whether such disasters are becoming more frequent, and what more can be done to prevent or prepare for them? Our study, published overnight in Nature’s, Scientific Reports, analysed patterns in the declaration of natural disasters in New South Wales and explored links between disadvantaged communities and those disaster declarations.

There's nothing natural about natural disasters

People talk about natural hazards and natural disasters as though they are the same – but they aren’t. Fires, floods and storms are not disasters, though they may threaten social systems or the environment as natural hazards. A disaster occurs when a natural hazard overwhelms a social system’s capacity to cope and respond, requiring a multiagency, coordinated response approach. Many factors such as vulnerability, resilience and population density influence a community’s coping capacity.

What types of disasters are most common?

Using data on Local Government Areas (LGAs) involved in Natural Disaster Declarations between 2004 and 2014 we examined three types of sudden hazards – bushfires, floods and storms. We Found LGAs in NSW were involved in disaster declarations on 905 separate occasions. Bushfires were the most common, responsible for 108 disaster declarations followed by storms (55) and floods (44) resulting in a total of 207 separate disasters between between these dates.

Across the state, 27 LGAs experienced no disaster declarations and they were all located within the Greater Metropolitan Region. LGAs involved in the highest number of disaster declarations were Clarence Valley (21), Richmond Valley (16), Narrabri (15) and Nambucca (15).

While bushfires were the most common type of natural disaster, floods affected the highest number of LGAs.

Disaster declaration analyses identified a cluster or ‘hotspot’ in the state's northeast and LGAs here were much more frequentlyinvolved in disaster declarations than elsewhere.

What is the key message for NSW, Australia and the world?

With clear differences in the number and type of disaster declarations in different years, we explored the role of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle in driving these events. Bushfires were more common in hot, dry El Nino’s, and floods and storms in wetter La Nina’s. However, no statistically significant relationship was found.

This suggests that for NSW, the strength of the ENSO is not a good predictor of the number of bushfire, storm or flood disaster declarations that will be made. This might be because first, the declaration of an event is based on its socioeconomic and human impacts – not the physical size or intensity of the actual event.

Research shows that vulnerable, disadvantaged communities are more susceptible to hazards and disasters.

We used the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas data to identify potentially vulnerable communities. Of the fourteen rural LGAs in NSW that fell within the most disadvantaged category, six or 43% (Clarence Valley, Kempsey, Kyogle, Nambucca, Richmond Valley and Tenterfield) were located within the disaster ‘hotspot’.

The key message for Australia and the world is if we do not deal with the root causes of inequality, injustice, disadvantage and poverty, no amount of spending on disaster risk management will stem the ever-increasing disaster losses.

How can this information help manage disaster risk?

The overlap of disadvantage and frequent disaster declarations presents a challenge to communities, disaster management authorities and governments. However, increased funding to address social disadvantage in these communities may increase resilience to natural hazards, preventing them from becoming disasters.

Significantly, LGAs that experienced no disaster declarations were all in the Greater Metropolitan Region.

Areas with less experience of hazards have lower awareness of the risks posed by hazards, and respond less effectively as a result. Thus, though metropolitan areas are typically above the average for social advantage, if a disaster were to occur, the population here would likely be less prepared to cope with the impacts.

The promotion of community outreach and education programs may help increase general awareness of the risks and help communities become better prepared. Similarly, additional training and operational deployments for emergency services personnel to disasters elsewhere provides opportunities to gain insight and experiences which can be brought home.

The 2011 Queensland floods demonstrated the need for better education, risk communication and community awareness.

With flood declarations the most widespread across NSW, it would be prudent to focus on community education and engagement on this type of disaster as a means to increase community resilience and coping capacity.

As the damage bill from recent flooding across NSW tops $500 million, and the Bureau of Meteorology predicts an above average 2016-17 cyclone season, it is an apt time to pause and reflect on what drives people’s understanding of disaster risk and communities’ resilience.

This is an abridged version of an article co-authored by Associate Professor Dale Dominey-Howes in The Conversation.