Why media reform in Australia has been so hard to achieve

The government's proposed changes to media ownership laws are neither future-looking nor future-proofing, writes Associate Professor Tim Dwyer from the Department of Media and Communications.

The Australian media policy omelette cannot simply be unscrambled. Image: iStock.

From the mid-20th century, there has been substantial international support for plurality of media ownership. Policies designed to limit the number of media outlets owned or controlled by one proprietor have been seen as a precondition for achieving a diverse range of viewpoints.

The assumption has been that concentrated ownership confers undemocratic power on “influential” owners to sway governments and advance their own private interests.

But while the power of major media groups has long been recognised – particularly during elections – ruling political parties increasingly only make significant policy changes with an eye to the impacts on their media allies.

Consistent with other Western nations, Australia’s media ownership rules have become more deregulated since the 1980s. This has meant media ownership in Australia has become increasingly concentrated.

The Australian media policy omelette cannot simply be unscrambled, but forward-thinking diversity rules could help prevent further concentration of ownership. Communications Minister Mitch Fifield recently announced the Turnbull government would once again attempt to tackle media reform. However, the proposed changes are neither future-looking nor future-proofing.

Removing restrictions

Serious attempts at systemic reform to tackle a changing media landscape were last seen in the Convergence Review in 2012.

But its proposed changes, including the idea of a Content Service Enterprise (where regulation of content was to be applied equally regardless of the platform it was delivered on), were too threatening to incumbent players. The review was binned.

Prior to the cross-media laws being introduced in 1987, limits had applied to the numbers of media-specific outlets within a single sector. This meant media groups such as John Fairfax Holdings and the Herald and Weekly Times had previously been able to accumulate media outlets across platforms like newspapers, TV and radio. But it was considered not to be in the public interest to allow this kind of concentration of influence.

Later, in the deregulatory spirit of the times, successive Coalition governments from 1996 attempted to repeal laws aimed at tackling media concentration. Yet it took until 2006 for this goal to be achieved.

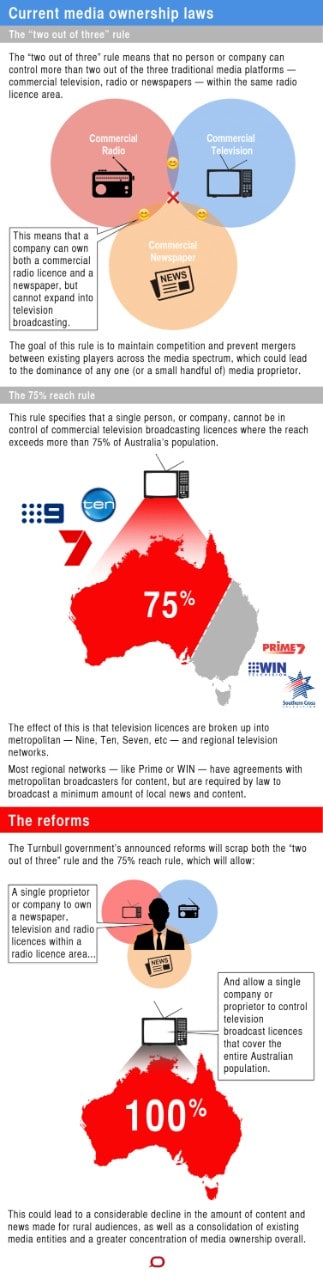

These changes removed the main cross-media ownership restrictions. They allowed TV/newspaper/radio mergers with a “two out of three” media sector limit, and introduced metropolitan and rural/regional voice limits under the so-called “5/4 voices” test. The latter refers to the minimum number of media groups (or “voices”) allowed in metropolitan and regional markets respectively.

In spite of ongoing attempts, and largely due to a lack of industry consensus, conservative governments have been unable to remove the final ownership restrictions. But the Turnbull government says a consensus has now been reached.

The proposed changes to media ownership – axing the two-out-of-three rule and the 75% “reach” rule – are buried under more headline-grabbing measures. These include the removal of licence fees for commercial TV networks, the introduction of gambling ad restrictions on free-to-air licensees, and granting pay TV expanded access to sporting events previously on the anti-siphoning list.

Restricting gambling ads during daytime viewing has a clear community benefit. But the wider voice benefits of diversity that flow from retaining restrictions on the further concentration of ownership are far more consequential for all Australians.

Click here to enlarge.

Image: The Conversation CC BY-ND

A different approach

Australia’s media landscape is an outlier as one of the most highly concentrated in the world – ahead of Egypt and China, according to one international assessment. The proposed changes will only make that worse.

Radical changes in the news media sector urgently demand new policy responses to accommodate an industry in transition. Simply removing the last major remaining bulwark against the concentration of media voices is not the solution.

Repealing the two-out-of-three rule will not lessen the impact of internet hegemons Facebook and Google on news business models – they control around 90% of the growth in the online advertising market. That horse has long since bolted. But the rule continues to prevent further media concentration.

In addition to industry strategies, Australia needs to have a comprehensive review of how news is now consumed across online and traditional media. This would serve as a precursor to media diversity policies that tackle the changing news environment.

The UK’s Ofcom and the European Commission have made significant inroads into monitoring, researching and updating voice pluralism policies. Australia needs to take similar decisive action. This is even more urgent for Australia given the parlous state of our media diversity.

Ofcom, at the request of Culture Secretary Karen Bradley, will shortly decide whether a full takeover by 21st Century Fox of BSkyB is in the public interest. It will base its decision on broadcasting standards and media pluralism.

If media pluralism and the dominant influence of Rupert Murdoch’s companies on the news is a big concern in the UK, then the same issue is front and centre in Australia’s highly concentrated news sector. This is even more the case with a potential TPG buyout and likely asset-stripping of Fairfax Media.

The proposed removal of the two-out-of-three rule will only make Australia’s media more concentrated in Murdoch’s hands – for example, if News Corp bought the ailing Ten Network.

The media reform package smacks of the government doing deals with the incumbent commercial TV networks and News Corp’s Foxtel. It is a short-sighted political play, and not a serious attempt to tackle structural change in the media industries by looking at ways to maximise diversity for audiences.

Associate Professor Tim Dwyer is from the Department of Media and Communications. His research focuses on the critical evaluation of media and communications industries, regulation, media ethics, law and policy. This article originally appeared on The Conversation.