Australian artists go international, thanks to Paris fellowship

Artist Zanny Begg received the the Terrence and Lynette Fern Fellowship in 2016.

For decades, the apartment studios in Paris’ Cité Internationale des Arts have offered artists-in-residence from all over the world the space and time to create new work.

Each year, the Power Institute, the University’s foundation for art and visual culture, offers Australian artists, art writers and scholars the chance to spend three months at the Cité. The residencies – made possible by a gift from Terrence and Lynette Fern – have supported the creation of Australian work that has been exhibited internationally.

Here, three artists explain what the residency has meant for them.

Catherine O’Donnell in her studio.

Unlikely inspiration from the housing estates of Paris

On arrival in Paris, most sightseers head for the architectural landmarks in the heart of the city: Notre Dame, the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre’s glass pyramid. When artist Catherine O’Donnell arrived last year to begin her residency at the Cité, she headed in the opposite direction – to the city’s fringes, where housing estates loom in concrete blocks.

Though she was far from her home in the Blue Mountains, these places were familiar to O’Donnell, who grew up in the Green Valley housing estate in Sydney’s west. In her work, she draws suburban homes like the one she grew up in, transforming their fibro walls, wooden window frames and balcony railings into almost-abstracted geometric shapes.

She applied for the Paris residency because she wanted to see the housing estates of Europe that had influenced the Australian models. Without the support of the Terrence and Lynette Fern Fellowship, she would never have been able to make the trip.

“The financial support is one side of it,” she says, “but actually allowing yourself to do it is the other. To say, 'I can take three months out of my life to focus on my practice'. I felt so privileged to be able to go.”

She recently exhibited drawings from her time in Europe at an exhibition at May Space gallery in Waterloo. The fellowship, she says, will influence her work for years to come. “It really was a life-changing opportunity.”

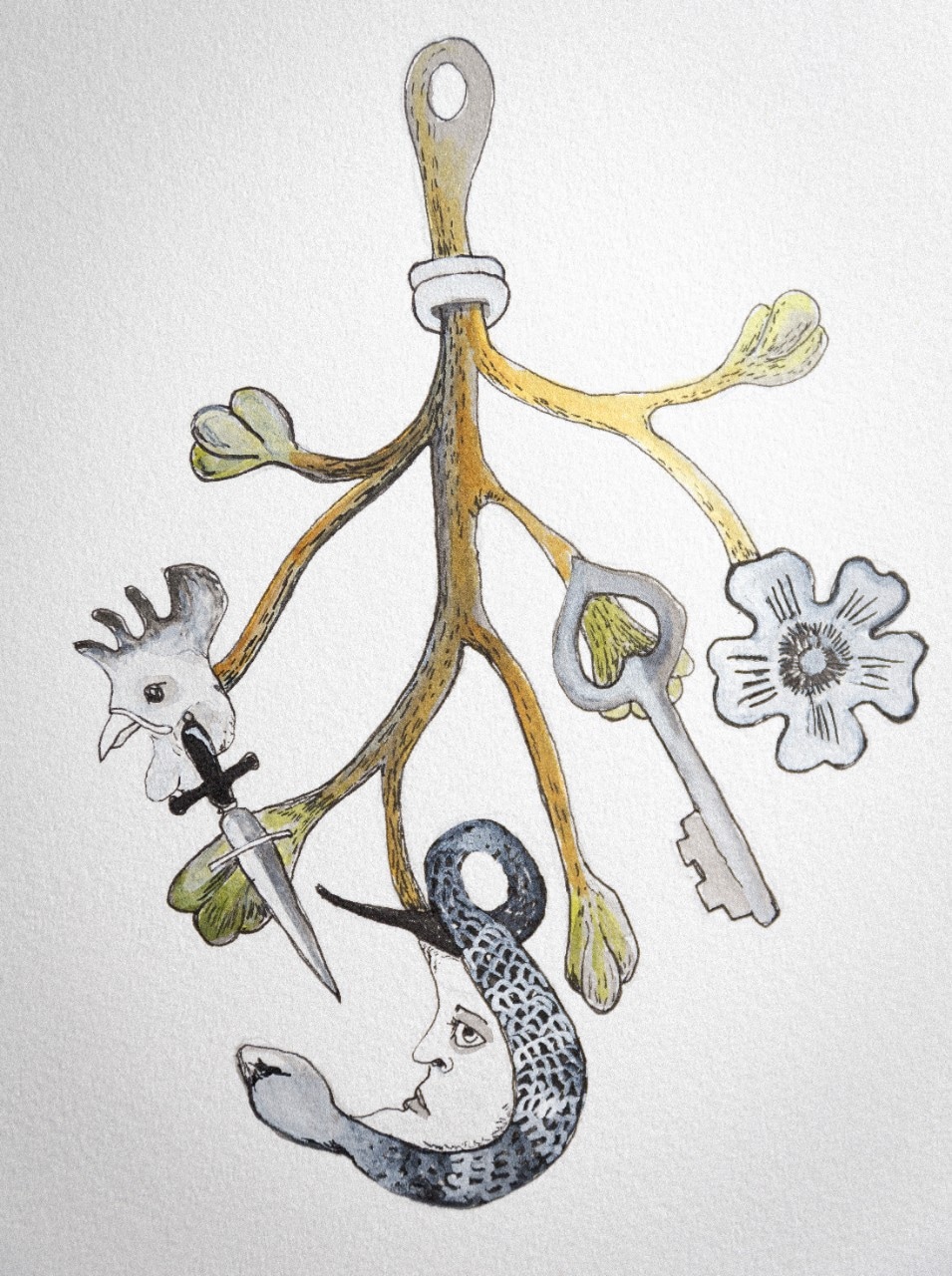

A drawing from the film installation, City of Ladies.

Film, feminism and friendship in France

When film installation City of Ladies screened at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 2017, south coast artist Zanny Begg — who made the work with Paris-based Australian director Elise McLeod — spent time in the gallery, watching and listening to audience reactions. Some people would weep. Others had intense discussions about the film’s themes.

Begg could not have made the film without the Terrence and Lynette Fern Fellowship. When she applied for the residency, she knew she wanted to work with McLeod, a childhood friend who had spent years living in France. She also knew she wanted to make a film about feminism.

Throughout her time in Paris, the idea developed. It draws on La Livre de la Cité des Dames (The Book of the City of Ladies) a 15th century work by medieval court writer Christine de Pizan, who imagined a utopia built, populated and governed by women.

In the film, Pizan’s story meets the ideas and concerns of contemporary female performers and activists. Viewers watch the film in a space wallpapered by Begg’s drawings, which riff on the medieval illustrations of Pizan’s book.

The work is now part of the Museum of Contemporary Art's permanent collection and has also been exhibited in Ukraine and Croatia.

“It seemed to really touch a nerve,” says Begg. “A lot of the issues [Pizan] was dealing with 600 years ago, we’re still dealing with today.”

Anne Graham in her studio in the Blue Mountains.

A treasure trove of ideas in Paris' museums and markets

Anne Graham’s studio in the Blue Mountains is full of treasures. One glass case holds a collection of antique combs. There are glass eyes, feathers and spools from old looms. She uses them in her installations, placing objects together to transform them into something new.

“A lot of my practice is to do with weaving implements, sewing implements, fishing implements, cooking implements and gardening implements,” she says. “Things you use.”

She went to Paris on the Terrence and Lynette Fern Fellowship with her husband, curator and writer Anthony Bond. Both had ideas to pursue. Bond conducted interviews for a coming book, while Graham spent time at the Musée des Arts et Métiers, researching the history of the Jacquard loom – a 19th century device that simplified textile production.

In the markets of Paris, she collected shuttles, bobbins and lace-making equipment. In the museums, she collected ideas. Her research eventually led to an interest in mathematicians Ada Lovelace and Alan Turing, whose work is connected to the technology of the Jacquard loom. Her work, Ada and Alan, is a sculptural portrait of the two, with a standing black crinoline representing Lovelace and a wooden Fibonacci spiral for Turing. It has been exhibited at the Bathurst Regional Art Gallery and the Glasshouse Regional Gallery in Port Macquarie.

Another work, House of Shade and Shadows — a black‑netted structure filled with hanging plants and bubbling fountains — was inspired by the glasshouses of Paris’ Jardin des Plantes.

For Graham, who collects and connects ideas and objects, travel is crucial. "If I’m home, I’d be thinking about cleaning the windows," she says. "When you’re somewhere else, you can totally focus on the idea and let it grow.”