Education brings a new future to 25 million children in Pakistan

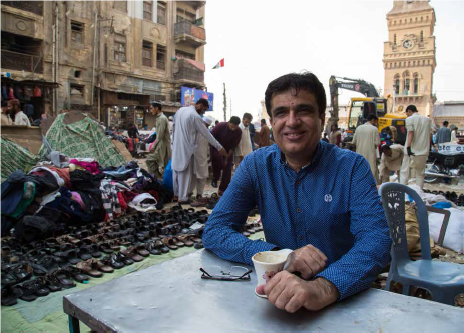

In his home city of Karachi, Lila Ram has dedicated himself to giving children a better future through education.

Discovering the world of books is still a clear memory for Lila Ram (MEd ’07). He was 12 years old and going to play at the home of his classmates, both children of a local school teacher. Their father, as Ram was about to discover, had a vast library. When he walked through the door and set eyes on the rows of books, Ram struck a secret deal with his friends: “I told them, ‘If I take one book and bring it back safely, can you give me another?’”

They agreed and Ram found himself quickly working his way through short stories, poetry and novels, many of which were translations of classics into his mother tongue, Sindhi. The school teacher father soon heard about the deal. “I was afraid he would be angry,” Ram remembers. Instead, he encouraged the young boy to keep borrowing.

This exposure to literature and learning was an opportunity for Ram that many Pakistani children still don’t have, especially in rural Pakistan, where he was born and grew up.

Pakistan has an estimated 25 million children who don’t go to school. The barriers to education include a preference for educating boys over girls, extensive use of corporal punishment, persistent poverty and hugely disruptive natural disasters. A lack of teacher training and infrastructure also affects the quality of education that can be delivered. As well, there are some rural areas of Pakistan where it’s said to be dangerous to go to school due to the activities of extremists.

Ram had another obstacle. His father passed away when he was aged two, leaving his mother to care for him and his three siblings in the poor rural town of Tando Bago in Pakistan’s Sindh province. As custom dictated, Ram’s eldest brother became the family breadwinner, though he was just a teenager himself.

A big priority is bringing girls into education. Part of this involves promoting sports and reading by distributing relevant materials in schools.

While many nearby towns didn’t have schools, Ram’s town did, thanks to a local philanthropist who took it upon himself to build one. Ram excelled at his studies, first at school and later at university. After graduating, he held down odd jobs, including writing and translating for magazines and other small publications.

It was translating educational books that gave Ram an insight that set him on a new path. “I noticed our educational resources for children weren’t based on science, logic and evidence,” he says.

“Education resources need to stimulate questions, an urge for more knowledge and a logical approach. This was lacking.”

These ideas stayed with him and he thought about them often. Ram finally landed a prestigious job as an engineer at a gas corporation, an opportunity that promised a great career. But he remembers looking out over the stretch of pipelines each day with the feeling there was something missing. “Every day when I came home, I found myself cursing my job,” he says.

With a wife and two small children to support, the thought of throwing in such a hard fought-for livelihood seemed near impossible. But Ram knew that what he really wanted to do was work in education. A job came up at a teachers’ resource centre in Karachi and he decided it was time. Ram took the job and has never looked back.

A typical school bag of a young student in Karachi.

Working at the centre, he was part of the effort to train teachers to rethink traditional teaching methods where the students are passive. Instead, the teachers were encouraged to be more student-centred, allowing students to actively shape and direct their learning.

Soon, Ram wanted to complement the hands-on experience in education and teaching with academic study. He heard of opportunities for postgraduate studies in Australia, but didn't see himself as a candidate as he thought such an offer was only for people from privileged backgrounds. And of course, it would mean being separated from his young family. It was only because of strong encouragement from friends and colleagues that Ram applied for a Master of Education (Research Methodology) at the University of Sydney.

In 2006, he arrived in Sydney, the furthest he had ever been from home. Adapting to a new country and a new education system was a huge challenge. Ram says he made it through thanks to the University academics and counsellors who also became friends. They still catch up regularly via email.

On returning to Pakistan, Ram was chosen from a large number of applicants for a role with the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), managing schooling programs. Today, he works for another international development aid agency.

Much of his work is in the field, monitoring the basic education programs he helped set up. These programs aim to increase the enrolment and retention of students, especially girls, in public schools which were severely affected by catastrophic floods in 2010 and 2011. There is also a focus on improving education and promoting health and hygiene in marginalised rural communities.

Here was a nine-year-old boy who preferred to walk four kilometres to another school that doesn’t beat its students, because he wants to learn.

Ram is part of the push to retrain teachers in Pakistan so they involve students more actively in the learning process.

Several experiences have stayed with Ram. After those devastating floods in rural Pakistan, temporary tent schools were erected in what are called Internally Displaced Persons camps. In the tents were hundreds of little girls going to school for the first time. Ram remembers the delight in their eyes as they first took a pencil in their hand, then seeing their pride in eventually being able to read, write, and draw.

Another memorable experience was encountering a little boy walking along a long road in a rural area. Ram stopped to ask where he was going and was told “school”. Ram asked why he didn't go to the local school. The boy said it used too much corporal punishment.

“Here was a nine-year-old boy who preferred to walk four kilometres to another school that doesn’t beat its students, because he wants to learn,” Ram says. The encounter led him to engage with the school to end its culture of corporal punishment.

Ram is still as passionate about reading as he was when he was 12, and regularly has his own writing published. He is an admirer of the famous Sindhi poet Bhitai, and was also influenced by Leo Tolstoy, a writer deeply concerned about the lives of the poor, who used writing to change society. Ram works in education because it too has transformative power.

“Education is all about changing lives,” he says. “It is about self-esteem, about giving our children the skills not just to cope with life and survive, but to become responsible citizens of Pakistan and promote peace, harmony and equality in society.”

Written by Cybele McNeil

Photography by Danial Shah