The huge history of big hair bows

A sea of oversized hair bows bobs through primary school gates each morning. It might be dismissed as a harmless children’s fad but big bows are back, driven by current fashions, tween influencers and celebrities.

Hair bows have a long history that includes the cushiony large posh bows of the 1980s, and more recently Lady Gaga’s hair bow made of hair. In the 1940s, teenage girls wore hair bows as signs of sexual availability.

Over the last century or so they’ve signified femininity, but historical sources indicate it wasn’t always that way.

For the boys

The hair bow was originally gender-specific to adult males in Europe throughout the 1700s when men adorned their hair with bows to show they were prosperous and extravagant.

Women also wore extravagant hairstyles, but these did not often feature hair bows; rather large ornaments and jewels were preferred.

After the French Revolution extravagance in dress and hairstyle was frowned upon and hair bows were rarely worn. By the 1800s it became common for male children to wear hair bows tying hair at the nape of the neck.

Women throughout the 19th century wore hair ornaments and hats, but the hair bow only really achieved widespread popularity in the 20th century before the second world war.

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, The House of Cards, 1736-37. Credit: Wikimedia.

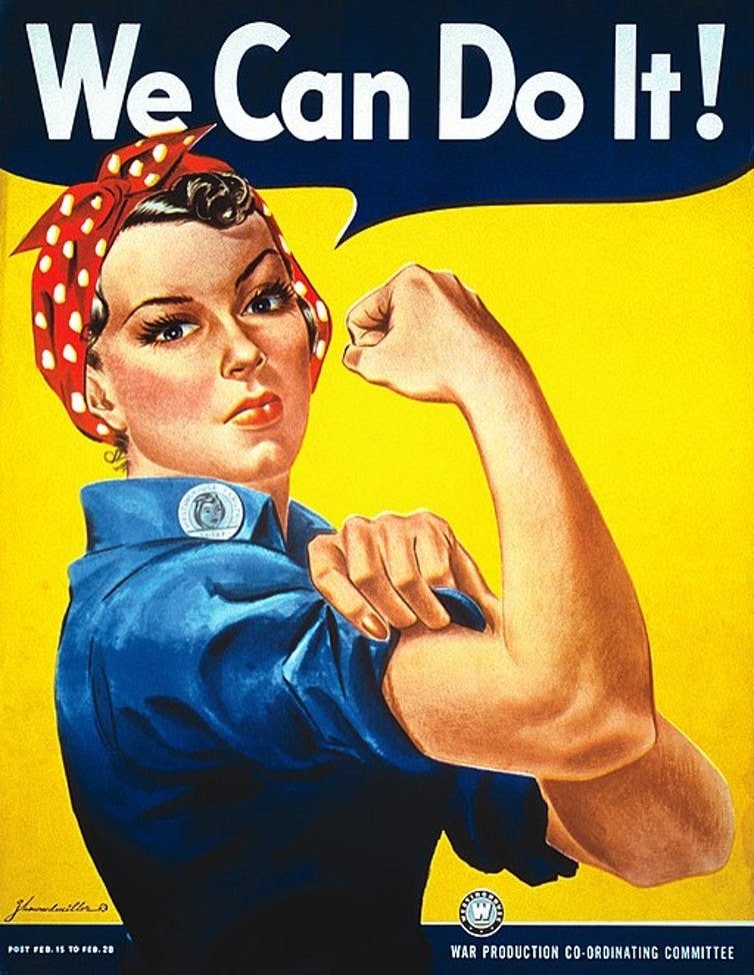

Poster by J. Howard Miller (1918–2004) used by the War Production Coordinating Committee. Credit: Wikimedia.

Pretty but strong

The hair bow today most commonly projects ideas of innocence linked to children and a concept of femininity as linked to qualities of gentleness, softness and compliance.

It may be precisely because the hair bow projects such ideals that it has also been employed as a means of empowerment for both female and male bodies.

During the war in 1942 the wartime propaganda We Can Do It poster – designed by Miller for Westinghouse Electric – appeared in the company factories to encourage women at work in the facilities.

The poster depicts an active female holding up her arm to show strength. She wears a red and white spotted scarf in her hair knotted at the top. The female body is presented as strong and able. The bow is minimal in size, and in this context also becomes functional – to keep the woman’s hair off her face – rather than simply decorative.

In the 1980s, singers Madonna and Boy George wore bows as symbols of feminine performance. Both pop icons wore the bow as a sign of celebration and transgression. The small fashion moment subtly exposed the social limitations of ideas of femininity.

Pop icon Madonna. Credit: Wikimedia.

Madonna wore the hair bow in a subversive manner, poking fun at social constraints projected onto the female body by being girlish and powerfully sexy at the same time.

The innocence of the girly bow, lollipops, white wedding dresses and religious iconography both in her name and the crucifixes she wore contrasted with the sexy and outgoing image she personally projected. Like the titles of her songs and albums – Material Girl, Immaculate Collection, Like a Virgin – the bow poked fun at how women are constrained by the stereotypes of innocence, virginity and femininity.

Meanwhile, Boy George, identifying as male, wore a hair bow during this period to perform femininity. In doing so, he highlighted the hair bow as something socially considered as limited to feminine presentation, but not necessarily limited to a female body.

Gaming gender

Today the hair bow is so intrinsically linked exclusively to femininity performed by a female body that we often see characters in games gendered simply by a hair bow.

In 1981, Ms Pac-Man was released in game form with a hair bow to distinguish her from the original male game protagonist.

Wendy O. Koopa of Super Mario fame relies mainly on a big pink polka dot hair bow (even though she has no hair), but gender is also indicated with a beaded necklace, large lips and long eyelashes. Super Mario character Birdo wears a large pink hair bow tied onto her head (like Wendy, the pink dinosaur does not have hair) and has been hailed as the first transgender game character to hit screens.

Nintendo game character Marmar is probably the most explicit use of the bow to indicate gender. She is a gold star with no other indicators except a big pink hair bow a third of the size of her body. We are familiar with bows as a way of marking femininity through characters such as Ub Iwerks and Walk Disney’s Minnie Mouse who debuted in 1928.

Teen pop star Jojo Siwa. Credit: Wikimedia.

JoJo with the bow bow

Most recently American child pop star JoJo Siwa’s iconic oversized bow has been the point of great fan connection with many children under 11 years old wearing the oversized and often glamorous bows in public.

Siwa, originally known for her role in reality-TV series Dance Moms (2014), connects with her fans through YouTube and a number of songs with dance videos such as Kid in the Candy Store (2016) and Hold the Drama (2014).

Her Facebook account has more than 6.2 million followers made up of mothers and fans from Australia, UK, US and New Zealand. There are many images of children wearing the bow and often they are pictured with their mothers, suggesting a bond of mother-daughter through femininity.

The JoJo bows are reminiscent of the white Soviet Union bantiki bows, worn from the 1940s on to show national allegiance.

Luxe for ladies

Bows have come back into fashion in the last few years: worn by the Duchess of Cambridge, Kate Middleton, and well-heeled celebrities like Nicole Kidman, Jessica Chastain and Margot Robbie.

The symbolism has been extended to high-end consumerism, with some bow-wearers repurposing the characteristic decorations on Chanel, Dior and Chloe shopping bags for their hair.

Though we’ve seen many man buns, the trend of hair bows for men has yet to return, and it may be some time before the bow transitions from necktie to men’s heads. If it does have a resurgence, we’ll know it’s nothing new.

Dr Fiona Andreallo is an honorary research fellow in the Department of Media and Communications. This article was originally published in The Conversation.