COVID-19 restrictions came at the right time: new study

The paper, from the University’s NHMRC Clinical trials Centre, published in Epidemiology and Infection, shows social distancing measures and border closures during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic coincided with a substantial reduction in new infections.

The analysis techniques, originally used to estimate HIV incidence in the 1980s and 1990s, could help inform future infection control strategies, as the nation relaxes restrictions and watches for a potential ‘second wave’.

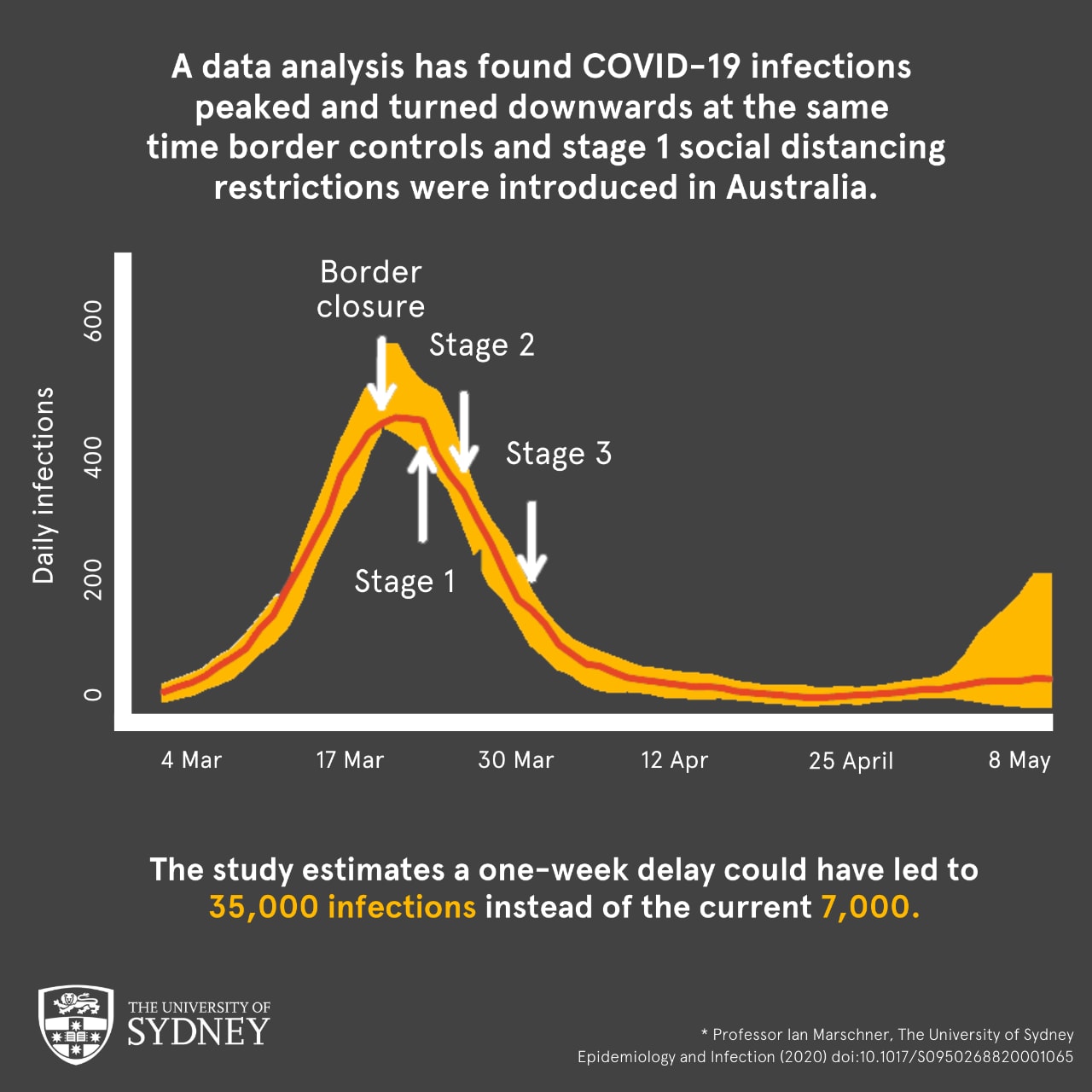

Additional analysis found a one-week delay in government action to flatten the infection curve, could have led to a five-fold increase in the total number of people infected. This would be 35,000 cases instead of the 7060 cases Australia currently has (as of 18th May 2020).

Professor Ian Marschner from the Faculty of Medicine and Health and NHMRC Clinical Trials Centre performed the analysis, and said just focusing on the number of new confirmed COVID-19 cases provided an incomplete picture.

“Daily numbers of new COVID-19 cases have been heavily relied upon by governments, researchers and the community, but they are a delayed indicator of what we are really interested in – the number of new infections,” he said.

“This is because there is a delay between COVID-19 infection and when it is officially diagnosised with a positive test. What’s more, the length of delay can vary greatly between individuals.

“These data analysis techniques allow us to explore the impact of control measures as they were implemented.”

Key findings

The study found new infections peaked and turned downward at the same time the federal government introduced border controls (20 March) and Stage 1 social distancing restrictions (23 March) – showing that the infection control measures came at a critical point in successfully managing the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia.

“We can’t learn this just by looking at the confirmed case numbers, which continued to go up even after these initial control measures were introduced,” said Professor Marschner.

The analysis also estimated that during mid- March as new infections were on the rise, up to three-quarters of all past infections were not yet diagnosed, potentially leaving a large pool of infectiousness in the community. This has now been reversed, and almost all infections are now diagnosed.

The study showed that the infection control measures came at a critical point in successfully managing the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia.

Methodology

As information about new infection numbers cannot be obtained directly from confirmed COVID-19 case numbers, at the heart of the data analysis are two techniques: a probability model of the infection’s incubation period, and a computational algorithm.

The computational algorithm implements a process called statistical deconvolution, also called back-projection, which unravels information about new infections from the observed data on new diagnoses.

The process projects the data points, in this case the COVID-19 cases, ‘back in time’ using the probability model to estimate when the new infections occurred.

‘Back-projection’can also project forward to provide short-term forecasts on what could have been.

Data analytics to monitor the pandemic

Australia is entering a pivotal point in the pandemic as the government eases social distancing restrictions.

If a second wave of infections does occur, Professor Marschner said it may take weeks for this to be reflected in the confirmed case numbers.

However back projection calculations are dependent on a detailed level of knowledge of the data parameters, such as virus incubation and diagnosis times.

Professor Marschner says as the pandemic evolves on a daily basis, this information will continuously need to be updated. This should be a high priority for COVID-19 epidemiological research, and would require close collaboration between modellers and statisticians.

“Applying the analytical tools used in this study can determine whether the timing of a second wave coincides with the easing of control measures and could be instrumental in guiding subsequent responses to managing the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia.”

Declaration: Professor Marschner declares no competing interests.