Secret of Australia's volcanoes revealed

Geoscientists collecting crust samples on the CSIRO ship RV Investigator. Lead author Dr Ben Mather is third from right.

Australia’s east coast is littered with the remnants of hundreds of volcanoes – the most recent just a few thousand years old – and scientists have been at a loss to explain why so many eruptions have occurred over the past 80 million years.

Now, geoscientists at the University of Sydney have discovered why part of a stable continent like Australia is such a hotbed of volcanic activity. And the findings suggest there could be more volcanic activity in the future.

“We aren’t on the famous Pacific ‘Ring of Fire’ that produces so many volcanoes and earthquakes,” said Dr Ben Mather from the School of Geosciences and the EarthByte group at the University of Sydney.

“So, we needed another explanation why there have been so many volcanoes on Australia’s east coast.”

Many of the volcanoes that form in Australia are one-off events, he said.

“Rather than huge explosions like Krakatoa or Vesuvius, or iconic volcanoes like Mount Fuji, the effect is more like the bubbles emerging as you heat your pancake mix,” Dr Mather said.

Their remnants can look like regular hills or notable structures like Cradle Mountain in Tasmania, the Organ Pipes in Victoria, the Undara Lava Tubes in Queensland and Sawn Rocks, near Narrabri, in NSW. Many are yet to be identified, Dr Mather said.

So, what is happening?

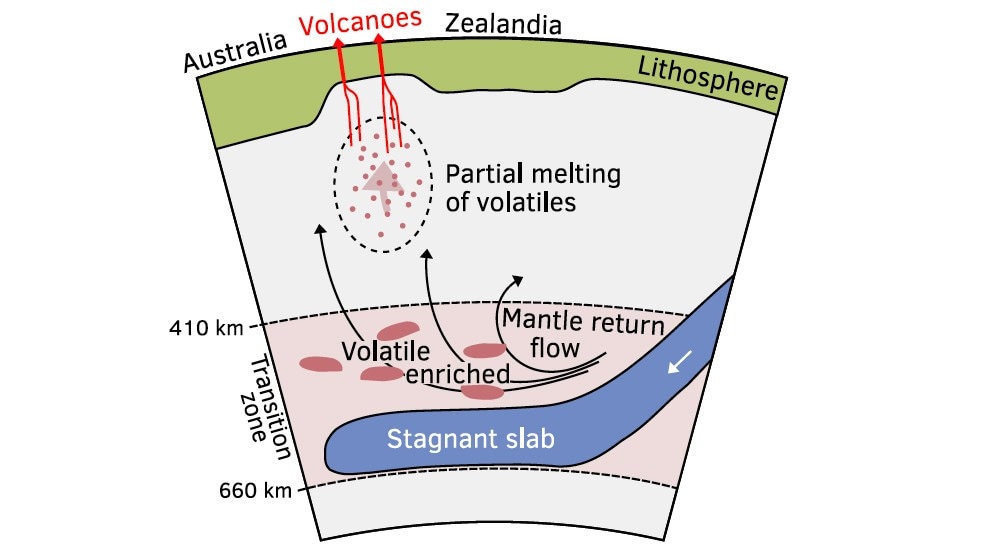

“Under our east coast we find a special volatile mix of molten rock that bubbles up to the surface through the younger, thinner east coast Australian crust,” he said.

The study is published today in the journal Science Advances.

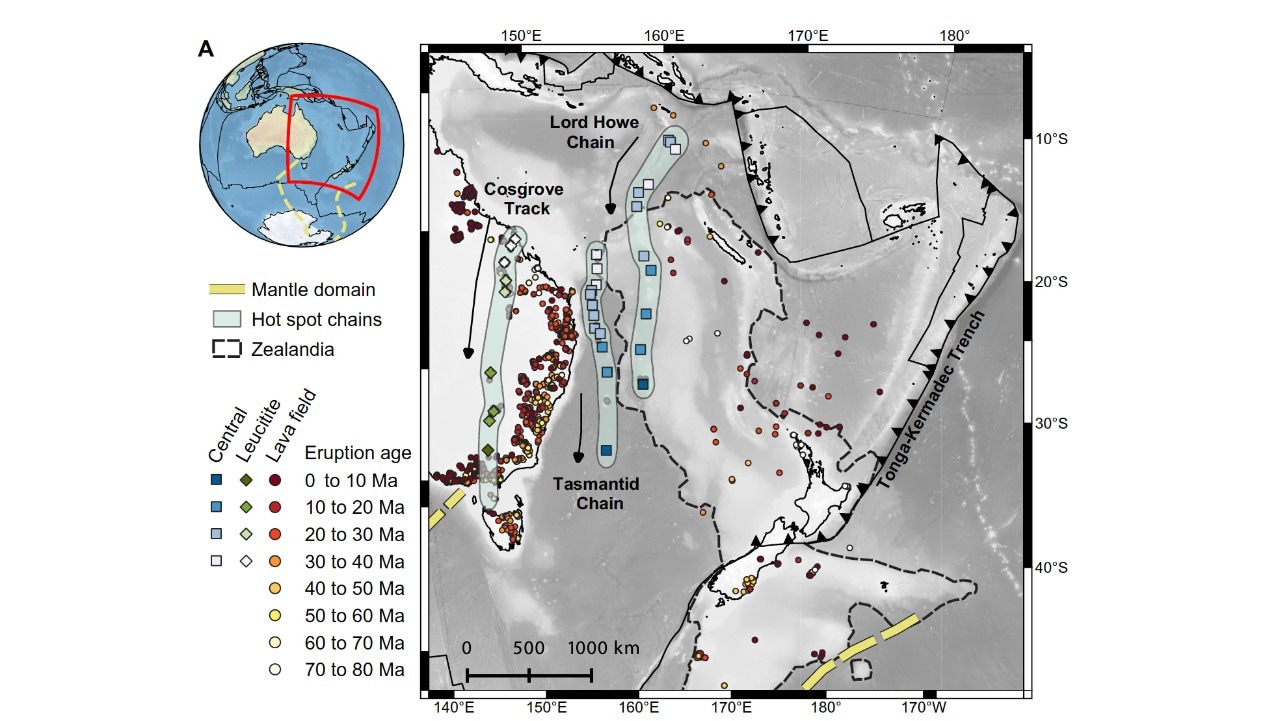

Dr Mather and his team looked at how hundreds of eruptions have occurred along the east coast from North Queensland to Tasmania and across the Tasman to the largely submerged continent Zealandia. They were particularly interested in ‘recent’ peaks of volcanic activity 20 million and 2 million years ago.

“Most of these eruptions are not caused by Australia’s tectonic plate moving over hot plumes in the mantle under the Earth’s crust. Instead, there is a fairly consistent pattern of activity, with a few notable peaks,” said co-author Dr Maria Seton, from the School of Geosciences and EarthByte group.

What tipped them off was that these peaks were happening at the same time there was increased volume of sea-floor material being pushed under the continent from the east by the Pacific plate.

Hundreds of volcanoes have dotted Australia’s east coast since the end of the dinosaur age 66 million years ago. This is caused by Pacific seafloor being pushed under Australia from the east at the Tonga-Kermadec trench.

“The peaks of volcanic activity correlate nicely with the amount of seafloor being recycled at the Tonga-Kermadec trench east of New Zealand,” Dr Mather said.

Taking this evidence Dr Mather and his team have built a new model that unifies the observations of so many eruptions occurring over millions of years along Australia’s east coast.

“The most recent event was at Mount Gambier in Victoria just a few thousand years ago,” he said.

While the model explains the consistent volcanic activity, it can’t predict when the next volcano will emerge.

How it happens

The sea floor of the Pacific plate to the east is being pushed under the Australian plate. This process is called subduction. The material is literally being pushed under the Australian continental shelf, starting at the Tonga-Kermadec Trench east and north of New Zealand.

“From there it is being slammed into the transition zone between the crust and the magma at depths of about 400 to 500 kilometres. This material is then re-emerging as a series of volcanic eruptions along Australia’s east coast, which is thinner and younger than the centre and west of the continent,” Dr Mather said.

Volcanoes emerge through the thinner east Australian crust as enriched mantle material bubbles to the surface.

This subduction process is not unique to the Australian east coast.

“What sets the east Australia-Zealandia region apart is that the sea-floor being pushed under the continent from the western Pacific is highly concentrated with hydrous materials and carbon-rich rocks. This creates a transition zone right under the east coast of Australia that is enriched with volatile materials.”

The new explanation improves on previous models that have suggested volcanoes in Victoria were due to convection eddies in the mantle from being near the trailing edge of the tectonic plate or models that relied on the plate passing over hot spots in the mantle.

“Neither of these gave us the full picture,” Dr Mather said. “But our new approach can explain the volcanic pattern up and down the Australian east coast.”

Dr Mather said this model could also explain other intraplate volcanic regions in the Western USA, Eastern China and around Bermuda.

Co-author Professor Dietmar Müller, Joint Coordinator of the EarthByte group in the School of Geosciences, said: “We now need to apply this research to other corners of the Earth to help us understand how other examples of enigmatic volcanism have occurred.”

The research, led by geoscientists at the University of Sydney was undertaken with researchers from Monash University and GNS Science in Dunedin, New Zealand.

Declaration

This study was supported by the NSW Department of Industry and the AuScope Simulation, Analysis & Modelling node funded by the Australian Government through the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy.