Myanmar's young protesters are funny, brave and media-savvy

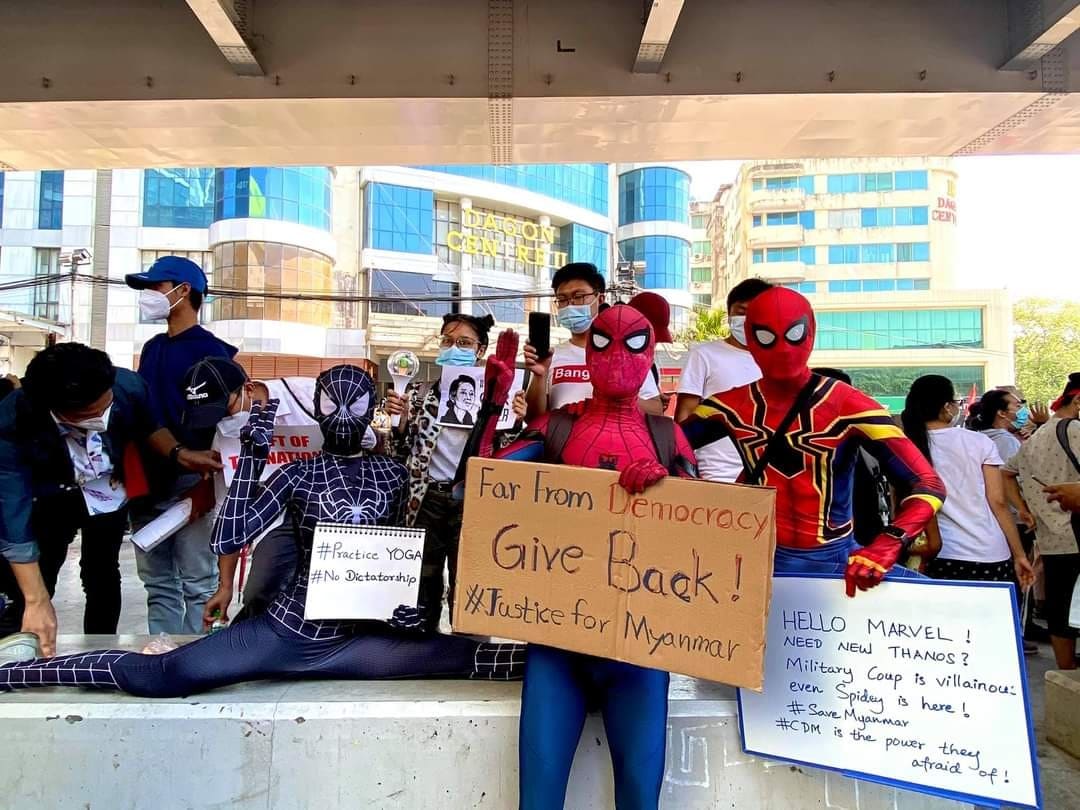

Protesters in Myanmar dressed as Spiderman. Photo: Twitter

For the past decade, sceptics of Myanmar’s transformation to civilian rule have warned that much of the country’s reform was cosmetic and that the military was still in charge. This month’s coup has proved these sceptics right. The changes of a decade ago did not give Myanmar a perfect democracy.

But with the opening of the country to popular culture, social media, and an emerging middle class, it did pave the way for something else: the young protesters who have taken to the streets, and who have not backed down even as violence escalates.

These young people – many of whom grew up listening to their parents talk about the 1988 protests and the subsequent military crackdown – are politically minded and globally connected. They are characterised by what they are, and by what they are not.

They are switched on to social media. Their appeals to reject the coup are funny and performative. They include references to popular culture, such as the three-finger salute of The Hunger Games, the walk of shame of The Game of Thrones, and a football team’s losing streak (Arsenal if you were wondering). They are absolutely abuzz on Twitter at #WhatsHappeninginMyanmar, posting photos of anti-coup body-builders and Marvel characters.

They are proving resilient. They quickly switched to Twitter when Facebook was banned by the military, amassing thousands of followers in a matter of hours. While very concerned about a night-time internet blackout imposed this week, they make jokes that at least they can get some sleep. They have been undeterred by the devastating shooting of a 19-year-old female protester, now brain-dead, to whom many could surely relate. In this way, they resemble student protesters of yesteryear, whose numbers only grew when students were shot dead by the military in 1988.

They are impressively disciplined. While their street performances may have levity, they are serious about the business of protesting, organising targeted campaigns, delivering food and water, distributing leaflets, and trying to protect activists from arrest. The fact that more than 500 towns have witnessed protests is due in large part to these efforts.

These young protesters are not a monolith. Their demands are diverse. Some ask only for the release of the woman they consider to be their leader, Aung San Suu Kyi. Others are more nuanced, demanding a revocation of the 2008 Constitution that enshrined power for the military, or they criticise China for blocking the United Nations Security Council’s condemnation of the coup and for its environment-damaging investments in Myanmar. Others are in open conversation with the erstwhile opposition.

It has been amazing to watch young activists try to win over the police who guard the streets, handing them red roses and chanting “pyithu ye” (our police). There have also been stirring exchanges between Rohingya refugees brutally expelled from Myanmar in 2017 (who now stand in solidarity in their refugee camps) and the protesters (who apologise for having never supported the Rohingya before).

Finally, these protesters are not alone. They are in union with the #CivilDisobedienceMovement, a growing cadre of civil service employees who are refusing to work. They are joined by the generation of ’88 protesters who are genuinely moved to hear young people sing revolutionary songs from three decades ago and appreciate the prowess and bravery of a new generation. And they are now joined by Myanmar’s monks, who have started to march in protests, projecting stirring images of orange and saffron punctuated by white placards.

But those of us watching from the sidelines should not be complacent about these energetic, innovative protesters. Myanmar’s military has waited on the sidelines before and only let loose the force of its repression after some weeks. If history is any guide, the military will not cave in easily, and large-scale violence is coming. New laws will make it easier to imprison protesters and shut down communication. Night-time arrests are on the rise. The military just released 23,000 (non-political) prisoners, including those who spread messages of hate against Muslims and are liable to stir up trouble. The jails are now uncrowded so there is more room to imprison people who dare to speak out.

I have several young former students from Myanmar who studied in Sydney. Now, they contact me when they can. Their message is quite clear: don’t let this fall out of the headlines. That might be what the generals are waiting for.

Myanmar’s activists, young and old, deserve that much from us.

Dr Susan Banki is a senior lecturer at the University of Sydney’s Southeast Asia Centre. Twitter: @susanbanki This article was first published in The Sydney Morning Herald. Top photo: Shutterstock