How will mass-vaccination change future COVID-19 lockdowns?

Sydney researchers have modelled and compared the effects of a hybrid vaccination program with efficacies similar to the Pfizer and AstraZeneca vaccines, to a high-efficacy vaccination program consisting of one vaccine, such as Pfizer. They have found the hybrid approach will not allow Australia to achieve herd immunity to COVID-19.

A team, led by Director of the Centre for Complex Systems from the University of Sydney, Professor Mikhail Prokopenko, found that herd immunity would not be achieved even if 90 percent of the population is vaccinated through a hybrid vaccination program, because of the choice to use a lower-efficacy vaccine for the bulk of the population. In addition, unvaccinated children may transmit the COVID-19 virus freely among their susceptible cohort.

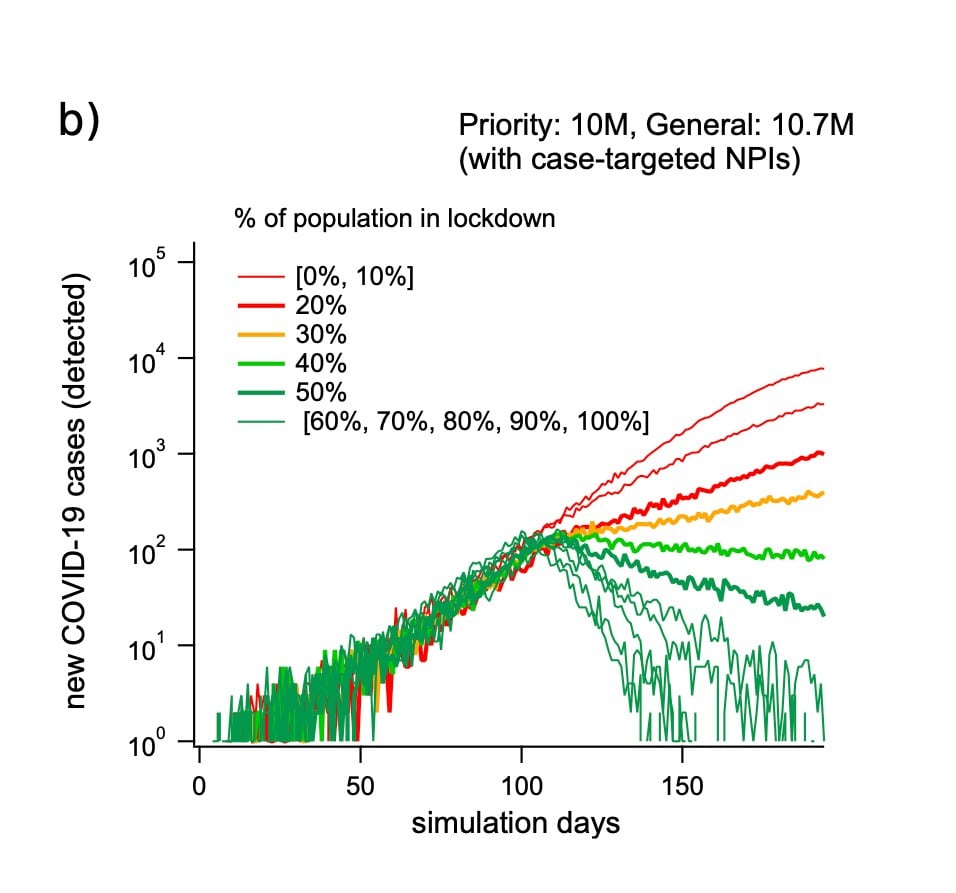

The model, which was published on pre-print server ArXiv and has not yet been peer-reviewed, simulated the effects of a vaccination program which comprised of 10 million people vaccinated with a priority vaccine, such as Pfizer, and 10.7 million people vaccinated with a general vaccine, such as Astra Zeneca. Despite a 90 percent vaccination rate, several million people would remain unvaccinated.

“The bad news is that the direct effect of having no herd immunity due to 10 percent of the population not being vaccinated is that there will continue to be a need for social distancing regimes, such as a partial lockdowns,” said Professor Prokopenko, who also conducts research as part of the Marie Bashir Institute for Infectious Diseases and Biosecurity.

“However, the good news is that once Australia’s hybrid vaccination program is rolled out, the need to comply with social distancing measures in the future will decrease. There will likely be small outbreaks, but vaccination of 90 percent of the population will necessitate only a 30-40 percent compliance with social distancing measures,” said Professor Prokopenko, whose team published key research in March 2020 which showed 80-90 percent of Australians would need to comply with social distancing measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 in 13 weeks.

“Without these partial restrictions, however, the outbreaks could still very well affect thousands or even tens of thousands of people.”

Australia’s current vaccination program involves a mass-vaccination approach in which a targeted group of the population comprising individuals in high-risk age groups, healthcare workers will receive the Pfizer vaccine, which has up to 95 percent efficacy. A remaining portion of the population will later receive the AstraZeneca vaccine, which has a lower efficacy.

“Had Australia opted to vaccinate the entire population with the Pfizer vaccine then herd immunity would be achieved by only vaccinating 70 percent of the population, whereas our current approach may see up to 90 percent of the population vaccinated without achieving herd immunity.”

This graph demonstrates how much of the population would need to comply with social distancing measures in the event of an outbreak under a hybrid vaccination strategy. If 90 percent of the population is vaccinated, 30-40 percent social distancing compliance is required to suppress an outbreak. Credit: Professor Mikhail Prokopenko, Dr Cameron Zachreson, Dr Sheryl Chang, Dr Oliver Cliff.

The study’s lead researcher, Dr Cameron Zachreson, said policy makers would do well to consider the potential implications of such a vaccination program.

“Even without herd immunity, vaccinating as many people as possible is highly beneficial as it improves clinical outcomes and, according to our model results, makes partial lockdowns more effective and easier to implement in the event of an outbreak.”

Dr Zachreson said there were several things to consider when allowing the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID-19, to circulate freely among children that involved the balance of potential short and long term risks.

“So far, we have seen that the disease’s severity is much lower in children, so there may not be a major short-term public health consequence to allowing transmission among this group,” said Dr Zachreson, who now works for the University of Melbourne’s School of Computing and Information Systems.

“However, the longer the virus stays around, the higher is its potential to change into new strains, become more transmissible, or not respond to vaccines. Another school of thought is that this young cohort may develop an ongoing immunity to COVID-19 –– however so far these scenarios are speculative.”

HOW THE MODELLING WORKED:

The modelling was conducted by Dr Cameron Zachreson, Dr Sheryl Chang, Dr Oliver Cliff and Professor Mikhail Prokopenko.

The study involved a large-scale, detailed simulation to inform high-level discussion and debate among academics about the importance and feasibility of herd immunity.

DISCLOSURE:

The study was published on pre-print server, arXiv, and has not yet been peer-reviewed. There are no conflicts of interest to declare.