People more confident about vaccines in countries where trust in science is high

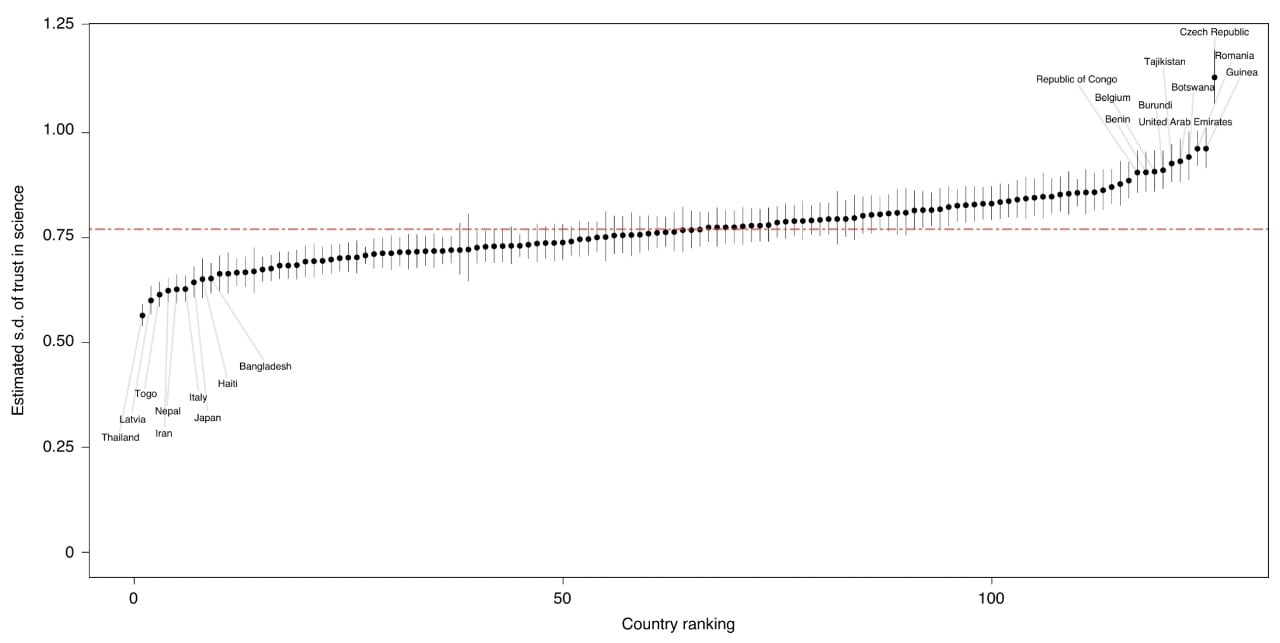

Strength of consensus around trust in science across countries. The horizontal dashed line is the global mean of standard deviation across countries. The researchers identify the countries with the lowest and highest estimated within-country standard deviations. Credit: Sturgis et al.

People are more likely to get vaccinated against diseases such as COVID-19 in countries where societal trust in science is high.

This is the key finding from a new report, published today in Nature Human Behaviour, from the University of Sydney, the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), and Surrey University.

In the study, the researchers used the biggest data survey on vaccine confidence (the 2018 Wellcome Global Monitor), covering over 120,000 respondents across 126 countries, to determine how trust in science across society drives vaccine confidence in individuals.

Trust in science is highest in Australasia, North America, and western Europe and lowest in South America, Eastern Europe, and Africa.

Previous studies have concentrated on individual trust in science and vaccines. However, the researchers found that confidence in vaccines or hesitancy towards them on a personal level is significantly linked to how much trust a country or society has in science.

The researchers note that thinking through the rights, wrongs, benefits, risks and hazards of a vaccine takes a lot of effort, especially if people have little experience or knowledge of the issue. People, therefore, rely instead on the ‘short-cut’ of trust (or mistrust) in science and scientists and will look to the attitudes and behaviours of others, often subconsciously, to determine what is normal and accepted.

Informal impressions of how science is valued or contested are picked up through social interactions, media representations and cultural and political debates. These factors combine to shape individual assessments about the trustworthiness of science.

The Wellcome Trust Monitor shows high levels of trust in science globally with more than four-fifths of people reporting ‘some’ or ‘a lot’ of trust in science. Confidence in vaccines was also relatively high with 81 per cent globally agreeing that vaccines are safe and 86 per cent agreeing that vaccines are effective.

Combatting COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy

With COVID-19 vaccination programs being rolled out in many countries across the world, the authors highlight the importance of understanding vaccine hesitancy. They argue understanding how a society feels about science can have a significant impact on individual uptake.

Co-author, Professor Jonathan Jackson, from the Department of Methodology at LSE and the University of Sydney Law School, says: “To be effective at eliminating viral infections, there needs to be widespread uptake of vaccines. Without high rates of population immunisation, the virus is likely to remain endemic.

“We find a similar ‘protective effect’ of trust in science—vaccine confidence is highest when most people in society believe that science should be trusted.”

Lead author, Professor Patrick Sturgis from the Department of Methodology at LSE, said: “The focus of global attention is likely to shift from vaccine supply to demand: the willing are jabbed and those still to receive the vaccine are hesitant or unwilling to receive it.

“It is now of pressing importance that social science develops a better understanding of what makes people confident to be vaccinated against COVID.

“Our study demonstrates the crucial importance of societal level factors in fostering vaccine confidence, particularly the benefits of a strong social norm to trust science and scientists.”

Declaration: The authors received no specific funding for this work.