You can help identify what’s killing lorikeets

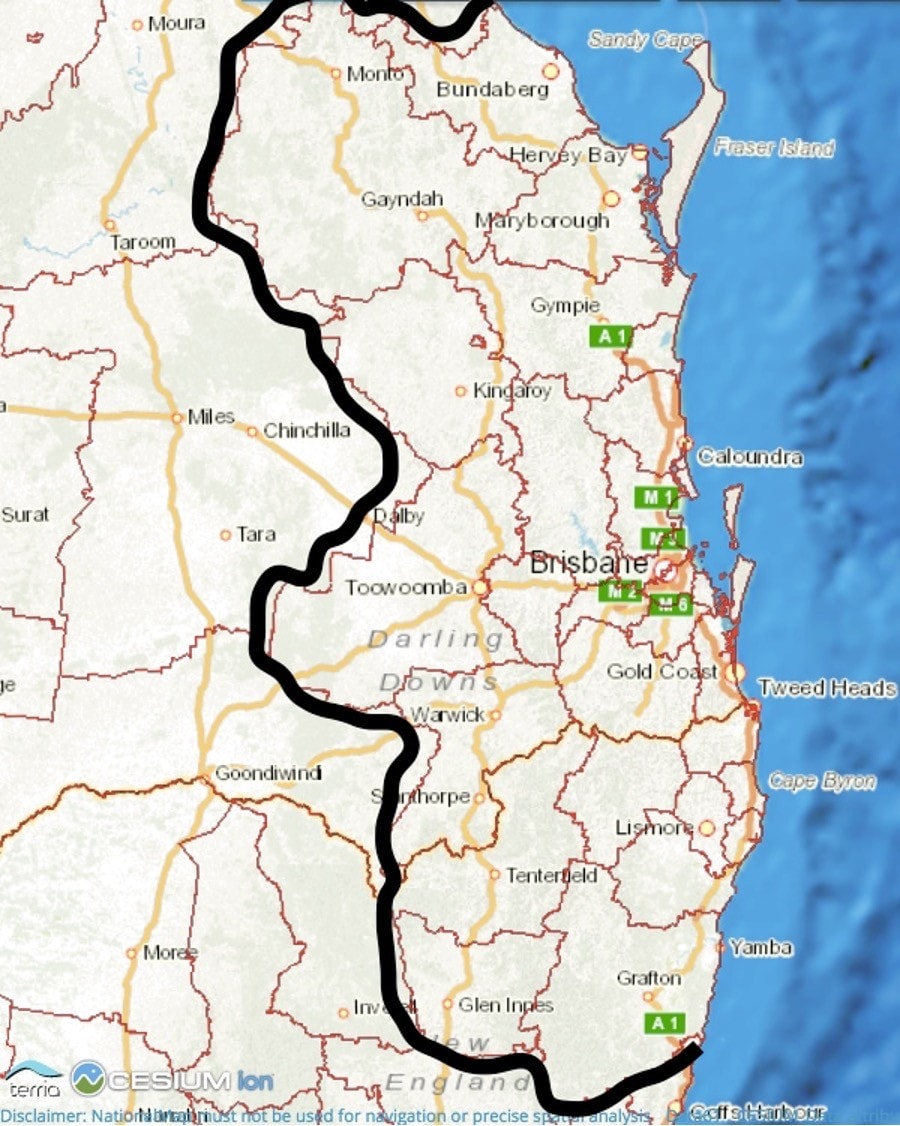

Distribution of known lorikeet paralysis syndrome cases.

A new study brings us one step closer to ensuring the health and wellbeing of wild rainbow lorikeets.

Researchers from the University of Sydney identified the prevalence, distribution, and manifestation of lorikeet paralysis syndrome – a seasonal disease (October to June) that affects thousands of rainbow lorikeets each year in northern New South Wales and southern Queensland.

The syndrome can cause limb, neck, and tongue paralysis, and an inability to blink or swallow, rendering birds unable to fly and feed, and therefore, survive.

“The number of cases each year ranges from hundreds to thousands, making it one of the most important wildlife diseases and animal welfare concerns in Australia,” said co-author, University of Sydney School of Veterinary Science Professor David Phalen.

The researchers are now calling on the public to help identify the likely source of the disease – a plant toxin.

Threat to Aussie treasure

Cases of lorikeet paralysis syndrome (solid blue circles) and non-lorikeet paralysis syndrome cases (empty circles) in the Sunshine Coast area (A) and Brisbane, QLD area (B). Clusters are shown as pink-filled circles and statistically significant clusters are indicated by cyan circles.

The researchers, including some from the RSPCA Queensland and the Taronga Conservation Society, examined lorikeet submissions to the RSPCA in 2017-18. Over a quarter of those submissions – 1,119 – were of lorikeet paralysis syndrome.

They identified lorikeet paralysis syndrome hotspots in Brisbane and the Sunshine Coast – but couldn’t determine why this was the case. What they understand, however, are the devasting effects of the disease.

“Not only can the syndrome prevent them from feeding and flying – it can render them prone to injury and predation,” Professor Phalen said. “This means they are more likely to run into objects or be hit by cars and be attacked by cats than those without the syndrome.”

To make matters worse, severely diseased birds are not good candidates for treatment. The study, published in Australian Veterinary Journal, found these lorikeets only have a 60 percent chance of recovery, and their treatment requires intensive care followed by extensive rehabilitation.

The prognosis is better for milder cases, which have a good (up to 84 percent) chance of recovery. An effective treatment could involve restoring kidney function, correcting electrolyte abnormalities, and relieving pain associated with muscle injury.

How you can help find the cause

Based on pathology findings, the researchers ruled out infectious disease like a virus as the cause of lorikeet paralysis syndrome. They settled on a toxin as the most likely cause – yet excluded known toxins that can cause neurological symptoms in wild birds, including pesticides, botulinum toxins and alcohol.

“This leaves us with the most likely suspect – a plant-derived toxin,” Professor Phalen said. “The seasonal occurrence of the syndrome suggests that the source of the toxin only blooms or has fruit during the warmer months and has a relatively limited range [northern NSW and southern QLD].

“Therefore, the next step is tracking blossoming and fruiting patterns of plants that lorikeets

feed on and correlating them with the areas in which lorikeets with the syndrome are found.”

Members of the public can help with this by reporting the plant species wild rainbow lorikeets are feeding on in a designated area that spans from northern NSW to southern Queensland. Learn more about this citizen science project and how you can get involved.

Lorikeet facts

- The rainbow lorikeet is a type of parrot with six subspecies

- They mainly feed on fruit, pollen and nectar

- Endemic to countries of the Pacific as well as coastal regions of northern and eastern Australia, with introduced populations in Perth and Tasmania, they are generally not considered threatened

- In fact, in WA, some consider rainbow lorikeets a threat to native species such as the black cockatoo, and a pest in terms of interference with agriculture

- Though some subspecies, like the Biak lorikeet of Indonesia, are threatened by habitat loss and capture for the parrot trade

- Lorikeet paralysis syndrome represents a serious threat to the species in specific regions

Declaration: Elements of this investigation were funded through Wildlife Rescue and Rehabilitation – an Australian Government initiative, the Sydney School of Veterinary Science, New South Wales Wildlife Information, Rescue and Education Service Inc. and National Significant Disease Investigation Program, Animal Health Australia.