Study challenges overheating risk for pregnant women exercising in the heat

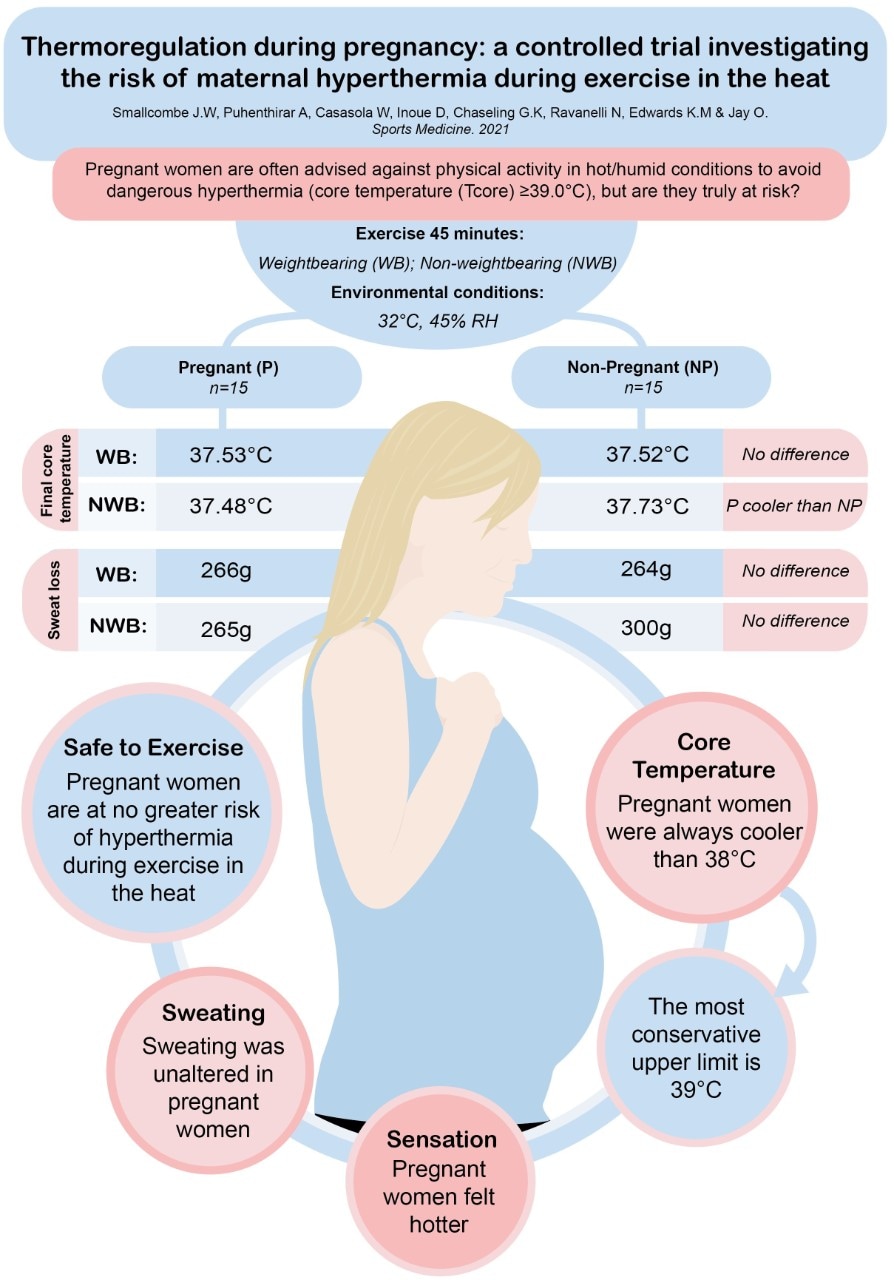

The findings question recommendations discouraging exercise in hot weather due to the potential risk to the unborn child associated with ‘overheating’ or maternal hyperthermia, defined as a rise in core body temperature above 39°C or 102°F.

The research is led by the University of Sydney’s Thermal Ergonomics Laboratory and was recently published in Sports Medicine.

“This is the first study to show that pregnant women can safely engage in moderate-intensity exercise for up to 45 minutes at up to 32°C (90°F) and 45 percent relative humidity with minimal risk of overheating,” said senior author Professor Ollie Jay of the University of Sydney’s Faculty of Medicine and Health and Charles Perkins Centre.

“This is important information, given the increasing temperatures globally and the well-known downstream benefits of regular physical activity throughout pregnancy to both mother and child”.

How was the study conducted?

Researchers conducted the controlled experimental study in a state-of-the-art climate chamber which allowed them to simulate typical Australian summertime conditions of 32°C (90°F) and 45 percent relative humidity.

The study involved 15 pregnant women in their second or third trimester and 15 non-pregnant control participants. The women exercised at a moderate intensity for 45 minutes on two separate occasions, with one trial simulating weight-bearing exercise (e.g. walking/running), and the other simulating non-weight-bearing exercise (e.g. cycling).

Thermoregulatory responses (core temperature, whole-body sweat loss, whole-body thermal sensation, heart rate and blood pressure and metabolic data) were also measured.

Whilst there was a small sample size, the robust design of the study (conducted under carefully controlled laboratory conditions so that other contributors of thermoregulatory “noise” were minimised) enabled the researchers to soundly determine with a high level of confidence whether any thermoregulatory differences existed between pregnant and non-pregnant participants. The study found the relatively low core temperatures in exercising pregnant women were consistent across participants irrespective of gestational age above 23 weeks.

What did they find?

Infographic by Sarah Carter, Thermal Ergonomics Laboratory, University of Sydney

- Women in their 2nd and 3rd trimester can perform 45 minutes of moderate intensity cycling or jogging/brisk walking exercise at 32°C (90°F) and 45 percent relative humidity with a very low risk of maternal hyperthermia – defined as a maternal core temperature >39.0˚C (102˚F).

- Throughout 45 minutes of continuous exercise in the heat, no pregnant participant recorded a core temperature over 38°C (100°F), which is 1˚C (1.8˚F) below the most conservative threshold for an elevated risk of temperature-related adverse birth outcomes.

- No meaningful differences in mean skin temperature or sweating were observed between pregnant and non-pregnant participants during exercise. These are important factors that regulate the body’s ability to keep cool.

- Despite no differences in body temperature, pregnant women did report feeling hotter.

The study did not involve pregnant women in their first trimester, with the youngest gestational age of a participant being 23 weeks. However, based on the evidence gathered, the researchers do not foresee any reason why the thermoregulatory responses would differ during the very early stages of pregnancy.

A significant step forward

Co-first authors Dr James Smallcombe and Ms Agalyaa Puhenthirar said the trial represented a significant step forward in this field of research.

“Prior to this research, experimental studies have only examined the thermoregulatory responses of pregnant women at temperatures as high as 25°C, which is far from representative of the hotter temperatures that are common during summers globally,” said Dr Smallcombe, postdoctoral researcher at the Thermal Ergonomics Laboratory.

“With limited evidence, public health discourse to date often states that women exhibit an impaired ability to regulate body temperature during pregnancy. Our data for the first time refute this notion,” said Ms Puhenthirar, a former student, whose honours project focussed on this question.

Declaration: The study was approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC No:2016/982). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.