Wildfires projected to grow by 50 percent, but governments are ill-prepared

Within the next 80 years, wildfires will become much more prevalent and severe globally. A new UN-commissioned report co-authored and co-edited by a University of Sydney professor sheds light on this and offers suggestions for prevention.

Climate change and land-use changes are projected to make wildfires even more frequent and intense, with a global increase of extreme fires of 14 percent by 2030, 30 percent by the end of 2050 and 50 percent by the end of the century, according to a new UN Environment Programme (UNEP) report launched today.

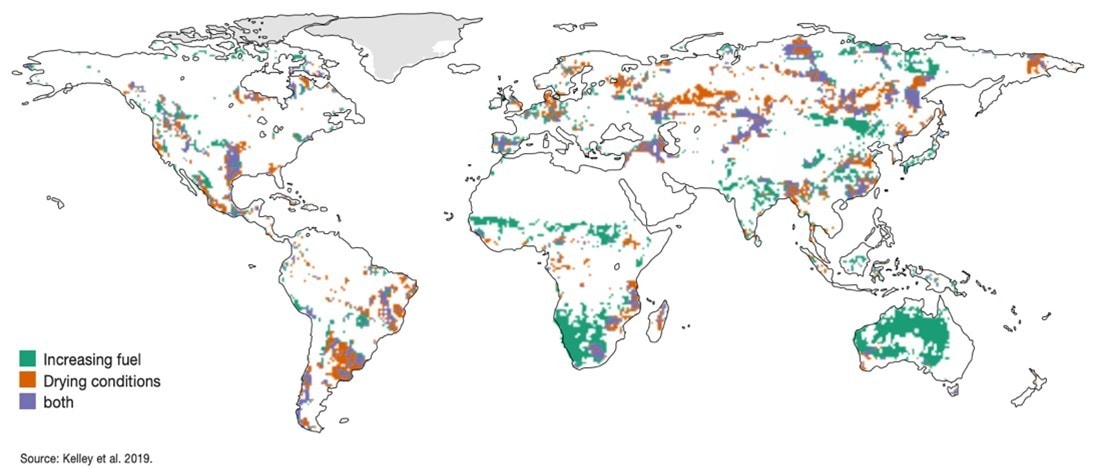

Increases in burnt areas, 2001-2014. Credit: GRID-Arendal/Studio Atlantis, 2021.

Australia, no stranger to wildfires – or bushfires as they’re known as here –has already seen a dramatic increase in the severity of this phenomenon over the past two decades.

Just this month, climate change-related wildfires destroyed at least five homes and 60,000 hectares (equivalent to 60,000 international rugby fields) of land in Western Australia. With the current La Niña weather system, our region is likely to see yet more wildfires develop, experts say, as wetter conditions allow plant life to flourish. When followed by drought, as the cycle typically operates, there will then be more fuel for the fires.

The report comes as koalas were announced as endangered in several states, in part because of reduced habitat following wildfires.

The new report that projects increases, Spreading like Wildfire: The Rising Threat of Extraordinary Landscape Fires, was released today by UNEP and GRID-Arendal, a UNEP collaborative communications centre. The report also finds an elevated risk in regions previously unaffected by wildfires, including the Arctic.

“Wildfires differ to ordinary, seasonal fires – they are uncontrollable,” said report co-editor and co-author, Professor Elaine Baker from the University of Sydney’s School of Geosciences.

“The Australian Black Summer bushfires of 2019-20, which killed 30 people and indirectly killed 450 others through smoke inhalation, are an example of this.”

Dropping water from helicopters is a sign of failure rather than hope

The authors are calling on governments to rethink spending, devoting a greater proportion to planning, prevention and preparedness. Currently, direct responses to wildfires typically receive over half of related expenditures, while planning and prevention receive less than one percent.

“Response rather than prevention is ineffective and endangers lives. Wildfires usually only cease when the weather changes. There are many actions that can help reduce wildfire risk, including learning from Indigenous knowledges and greater involvement of communities in planning and prevention,” Professor Baker said.

Inger Andersen, UNEP Executive Director, put it succinctly: “Dropping water from helicopters is a sign of failure rather than hope.”

Wildfires and climate change mutually exacerbating

With the proliferation of extreme weather events, such as droughts, wildfires are made worse by climate change. At the same time, climate change is made worse by wildfires, mostly by ravaging sensitive and carbon-rich ecosystems like peatlands and rainforests.

Report co-author, Dr Ayesha Tulloch from the University of Sydney’s School of Life and Environmental Sciences, said: “Fire is changing because human activities have changed the landscapes and the weather conditions in which it occurs. It’s not going to magically stop no matter what we do, but if we manage our landscapes better, we can significantly reduce its impacts on us and on nature.”

Wildlife and its natural habitats are rarely spared from wildfires, pushing some animal and plant species closer to extinction. A recent example is the Australian 2020 bushfires, which are estimated to have wiped out or displaced billions of domesticated and wild animals. “Some native animals and plants had almost their entire range burnt in those fires”, Dr Tulloch said. She added: “They are now restricted to only a few last places, so both burnt and unburnt places need to be carefully managed to ensure that these species can move back when the time is right.”

Acute and chronic health effects

“The health impact of wildfires is rarely considered,” said Professor Baker, who, with her colleagues, is calling for stronger international standards for the safety and health of firefighters. Aside from the immediate danger wildfires present to frontline firefighters, inhalation of toxic smoke by surrounding residents can cause acute and chronic health issues. Pollutants can damage lung tissue and exacerbate respiratory illnesses such as asthma, or even other conditions like heart disease.

“In NSW during Black Summer in 2019-20, for example, many residents – even those in inner-city areas of Sydney – were exposed to the fires’ dangerous chemical cocktail,” Professor Baker said. “Not only was it physically harmful – it cost the government over $1 billion in health expenditure.”

Poor affected more

As humans encroach on natural landscapes due to urban sprawl, they can become more vulnerable to wildfires. Undeveloped land, further from metropolitan centres, is cheaper and often unregulated in terms of risk. For example, after recent Californian wildfires, several insurers indicated they were no longer willing to underwrite homes in fire-prone areas, leaving residents physically and financially defenceless.

In developing countries, however, the impacts are even more dire. Wildfires disproportionately affect the world’s poorest nations, which often do not have the funds to rebuild decimated regions; care for those with fire-related illness; and sanitise waterways degraded by wildfire pollutants.

Professor Baker said: “A more coordinated approach between UN agencies could help developing countries prepare and also recover from the otherwise potentially long-term social, economic and environmental impacts of wildfires.”

Prevention strategies

To prevent wildfires, the authors call for a combination of data-based monitoring and Indigenous knowledge, and for stronger regional and international cooperation.

“Indigenous Australians have skilfully used fire to care for their environments for thousands of years,” Dr Tulloch said. “There are a growing number of ’on-country’ Indigenous fire partnerships across Australia that focus on cultural burning practices to prevent wildfires and conserve wildlife, but we need a lot more recognition and support for Indigenous cultural fire management both in Australia and overseas”.

They also propose new policies, legal frameworks, and incentives that encourage appropriate land and fire use to be implemented. Wetland restoration and building at a distance from vegetation are examples of investments that could be made.

Dr Tulloch said: “It’s much cheaper to invest now to try to reduce the likelihood of future megafires occurring, by building strong, healthy ecosystems that are resilient into the future – it could save us billions of dollars not just from reduced health costs but from protecting nature and its important services, like clean water, from harm.”

Declaration: Funding for the report was provided by UNEP; GRID-Arendal; the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Finland; and the Norwegian International Climate and Forest Initiative.