Fifth of global food-related emissions due to transport

In 2007, ‘locavore’ – a person who only eats food grown or produced within a 100-mile (161km) radius – was the Oxford Word of the Year. Now, 15 years later, University of Sydney researchers urge it to trend once more. They have found that 19 percent of global food system greenhouse gas emissions are caused by transportation.

This is up to seven times higher than previously estimated, and far exceeds the transport emissions of other commodities. For example, transport accounts for only seven percent of industry and utilities emissions.

The researchers say that especially among affluent countries, the biggest food transport emitters per capita, eating locally grown and produced food should be a priority.

Food transport emissions add up to nearly half of direct emissions from road vehicles.

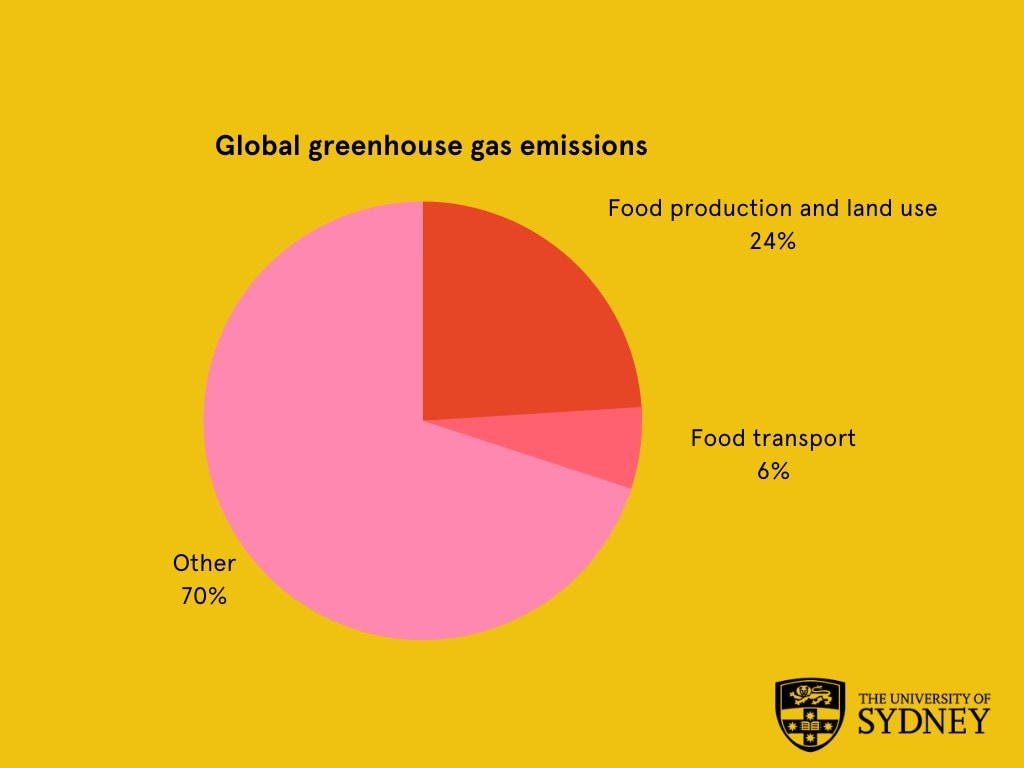

Dr Mengyu Li from the University of Sydney School of Physics is the lead author of the study, published in Nature Food. She said: “Our study estimates global food systems, due to transport, production, and land use change, contribute about 30 percent of total human-produced greenhouse gas emissions. So, food transport – at around six percent – is a sizeable proportion of overall emissions.

“Food transport emissions add up to nearly half of direct emissions from road vehicles.”

Nutritional ecologist and co-author, Professor David Raubenheimer from the Charles Perkins Centre, said: “Prior to our study, most of the attention in sustainable food research has been on the high emissions associated with animal-derived foods, compared with plants.

“Our study shows that in addition to shifting towards a plant-based diet, eating locally is ideal, especially in affluent countries.”

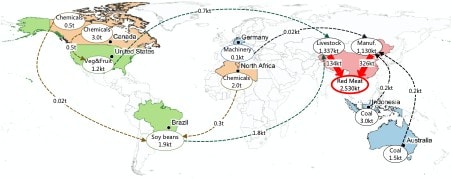

Examples of supply chains terminating in red meat consumption by households in China. Circles represent food production emissions; arrows represent transport emissions. Credit: Dr Mengyu Li/USYD.

Rich countries excessively contribute

Using their own framework called FoodLab, the researchers calculated that food transport corresponds to about 3 gigatonnes of emissions annually – equivalent to 19 percent of food-related emissions.

Their analysis incorporates 74 countries (origin and destination); 37 economic sectors (such as vegetables and fruit; livestock; coal; and manufacturing); international and domestic transport distances; and food masses.

While China, the United States, India, and Russia are the top food transport emitters, overall, high-income countries are disproportionate contributors. Countries such as the United States, Germany, France, and Japan constitute 12.5 percent of the world’s population yet generate nearly half (46 percent) of international food transport emissions.

Australia is the second largest exporter of food transport emissions, given the breadth and volume of its primary production.

Transport emissions are also food type dependent. With fruit and vegetables, for example, transport generates nearly double the number of emissions than production. Fruit and vegetables together constitute over a third of food transport emissions.

“Since vegetables and fruit require temperature-controlled transportation, their food miles emissions are higher,” Dr Li said.

The locavore discount

The researchers calculated the reduction in emissions if the global population ate only locally: 0.38 gigatonnes, equivalent to emissions from driving one tonne to the Sun and back, 6,000 times.

Though they acknowledge this scenario is not realistic, for example, because many regions cannot be self-sufficient in food supply, it could be implemented to varying degrees. “For example, there is considerable potential for peri-urban agriculture to nourish urban residents,” co-author Professor Manfred Lenzen said.

This aside, richer countries can reduce their food transport emissions through various mechanisms. These include investing in cleaner energy sources for vehicles, and incentivising food businesses to use less emissions-intensive production and distribution methods, such as natural refrigerants.

“Both investors and governments can help by creating environments that foster sustainable food supply,” Professor Lenzen said.

Yet supply is driven by demand – meaning the consumer has the ultimate power to change this situation. “Changing consumers’ attitudes and behaviour towards sustainable diets can reap environmental benefits on the grandest scale,” added Professor Raubenheimer.

“One example is the habit of consumers in affluent countries demanding unseasonal foods year-round, which need to be transported from elsewhere.

“Eating local seasonal alternatives, as we have throughout most of the history of our species, will help provide a healthy planet for future generations.”

About FoodLab – a University of Sydney-led database

FoodLab is an extension of the Australian Industrial Ecology Lab (IELab) led by the University of Sydney. FoodLab data encompasses more than 200 countries and 6,000 sectors and can be used for many other food-related global studies.

--

Declaration: This research was financially supported by the Australian Research Council (projects DP0985522, DP130101293, DP190102277, LE160100066, DP200102585 and DP200103005, LP200100311, IH190100009) and the National eResearch Collaboration Tools and Resources project, through the Industrial Ecology Virtual Laboratory infrastructure.