How El Niño may impact the world's wheat and global food supply

The World Meteorological Organization has declared the onset of the first El Niño event in seven years. It estimates 90 percent probability the climatic phenomenon, involving an unusual warming of the Pacific Ocean, will develop through 2023, and be of moderate strength.

El Niño events bring hotter, drier weather to places such as Brazil, Australia and Indonesia, increasing the risk of wildfires and drought. Elsewhere, such as Peru and Ecuador, it increases rain, leading to floods.

The effects are sometimes described as a preview of “the new normal” in the wake of human-forced climate change. Of particular concern is the effect on agricultural production, and thereby the price of food – particularly “breadbasket” staples such as wheat, maize and rice.

El Niño’s global impacts are complex and multifaceted. It can potentially impact the lives of the majority of the world’s population. This is especially true for poor and rural households, whose fates are intrinsically linked with climate and farming.

"Despite the general inflationary pattern, there have rarely been big swings in El Niño years."

The global supply and prices of most food is unlikely to move that much. The evidence from the ten El Niño events in the past five decades suggests relatively modest, and to some extent ambiguous, global price impacts. While reducing crop yield on average, these events have not resulted in a “perfect storm” of the scale to induce global “breadbasket yield shocks”.

But local effects could be severe. Even a “moderate” El Niño may significantly affect crops grown in geographically concentrated regions — for example palm oil, which primarily comes from Indonesia and Malaysia.

In some places El Niño-induced food availability and affordability issues may well lead to serious social consequences, such as conflict and hunger.

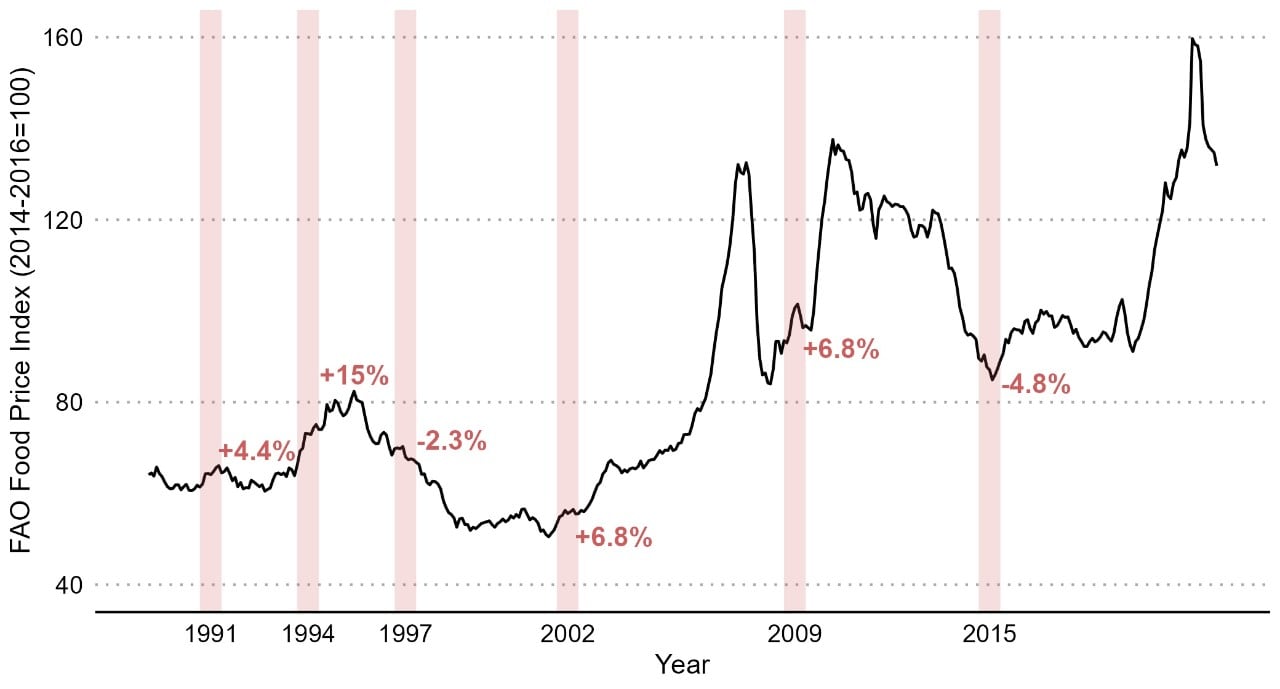

El Niño and global food prices

Despite the general inflationary pattern, there have rarely been big swings in El Niño years. Indeed, it shows prices decreasing during the two strongest El Niño episodes of the past three decades.

El Niño and global food prices

Changes in the Food Price Index, published by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Grey bars indicate El Niño years.

El Niño years are shown by nine-month periods centred on December (August to April). These are approximations and should be treated as indicative.

Other human-caused factors were at play – notably the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997, and the Global Financial Crisis in 2007-2008. In 2015, prices decreased due to stronger (than expected) supply and weaker demand, when the El Niño event did not turn out to be as bad as feared.

This all suggests that El Niño does not usually play the lead role in global commodity price movements.

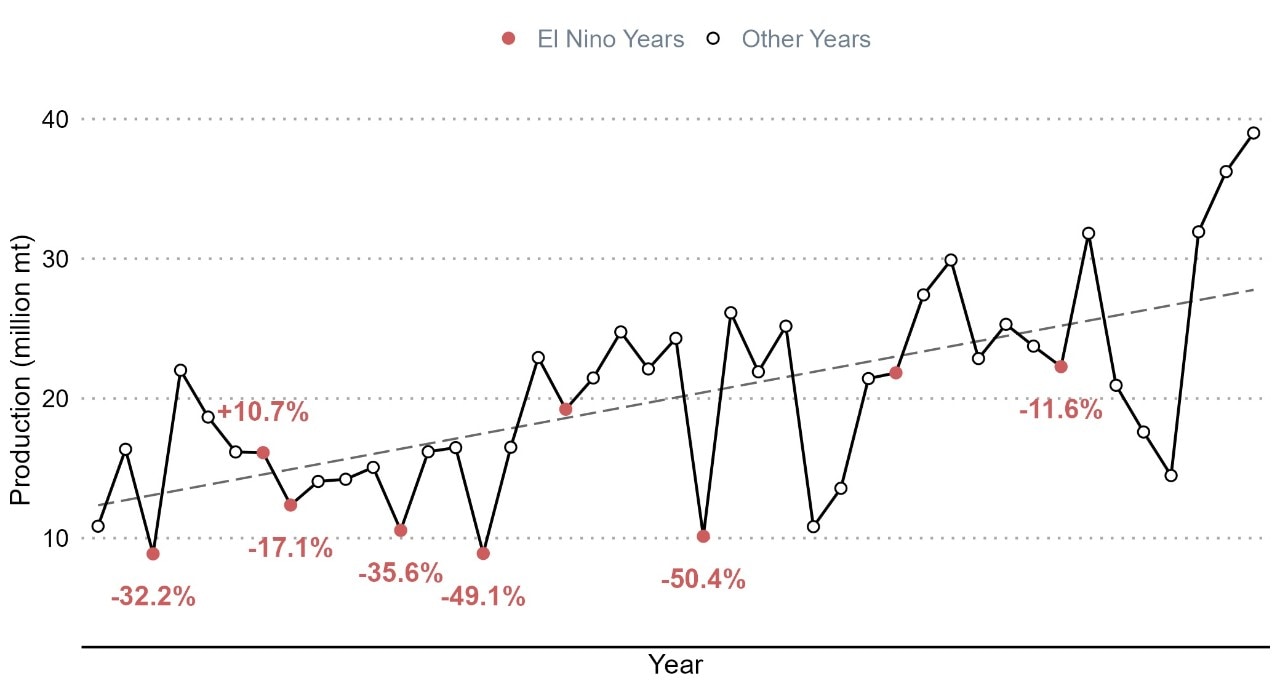

Impacts on wheat supply

Why? Because El Niño does induce crop failures, but for food grown around the world the losses tend to be offset by positive changes in production across other key producing regions.

For example, it can bring favourable weather to the conflict-ridden and famine-prone Horn of Africa (Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia).

A good example is wheat.

The following chart shows how El Nino has affected Australian wheat production since 1980. In six out of nine El Niño events of at least moderate strength, production has dropped significantly – in four cases, at least 30 percent below the “trend line” (representing the long-term average).

El Niño and Australian wheat production

Wheat production (in metric tonnes). Grey bars indicate El Niño years.

El Niño years are shown by nine-month periods centred on December (August to April). These are approximations and should be treated as indicative.

Australia is one of the world’s top three wheat exporters, accounting for about 13 percent of global exports. So its production does affect global wheat prices. But in terms of total wheat grown it’s less significant – about 3.5 percent of world production. And El Niño-induced crop failures tend to be offset by production in other key wheat-producing regions.

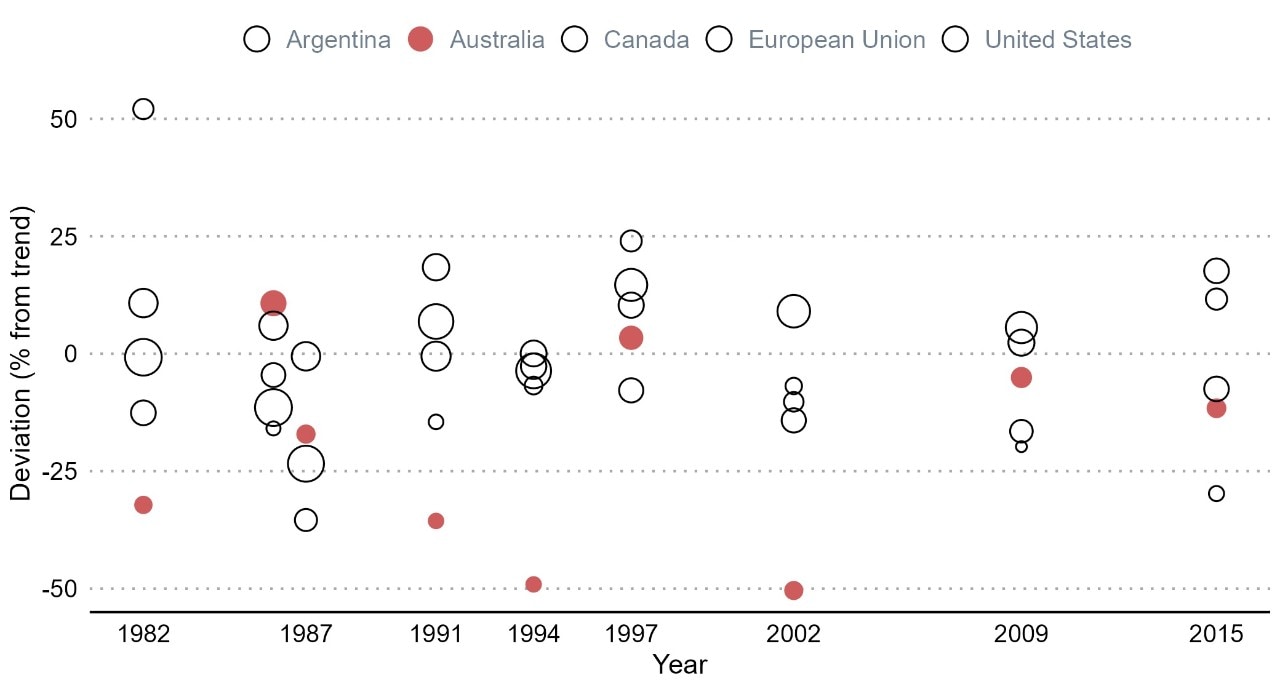

The next graph compares changes in Australia’s wheat production with other significant wheat exporters in El Niño years. Dips in Australia’s production tend to be offset by changes elsewhere.

El Niño effects on five major wheat exporters

Dots show percentage change in wheat production by El Niño year.

"Dips in Australia’s production tend tend to be offset by changes elsewhere."

In 1994, for example, Australian wheat production dropped nearly 50 percent but barely changed elsewhere. In 1982, when Australian production dropped 30 percent, Argentina’s production was 50 percent higher. Such balancing patterns tends to be present across most El Niño years.

But some will bear the cost

That said, there will be at least some negative effects. Even if crop failures in one region are fully offset by rich harvests in others, some people are going to bear the costs of El Niño’s direct impact.

Australian farmers, for example, will be worse off if local wheat yields drop while global prices remain relatively stable.

Moreover, because most countries are connected via trade, El Niño will have wider economic impacts. It could still lead to deeper societal issues in some region, such as famine and agro-pastoral conflicts.

These effects may also be nuanced. For example, poor harvests in Africa may mitigate seasonal violence linked with the appropriation of agricultural surpluses. But considering other vulnerabilities around the world, the odds are that even a moderate El Niño will make already dire socio-economic conditions in some countries worse.

Most of the usual warnings about the caveats of climate change apply here. The difference, of course, is that all this is happening now.

This article was originally published in The Conversation as: ‘What this year’s El Niño means for wheat and global food supply.’ It was written by Associate Professor David Ubilava from the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, who studies Agricultural Economics.

Graph Souce: Associate Professor David Ubilava, based on data from the United States Foreign Agricultural Service.