Day 1: Times Higher Education Summit 2023

Key sessions included:

- The next generation leadership model

- Leadership reflections: Nurturing diverse talent

- Closing the equity gap: Improving Indigenous access to higher education

- Creating a true interdisciplinary environment

- Leadership reflections: Building multidisciplinary research from the ground up

- Mobilising for disaster response and climate resilience

At the end of Day 1 of the Summit, Federal Minister for Education Jason Clare joined delegates on the lawns of the historic Quadrangle to celebrate the coming together of the global higher education community.

Welcome to Country and opening remarks

Nearly 600 higher education leaders from across the world converged upon the University of Sydney this morning for the start of the flagship Times Higher Education World Academic Summit 2023.

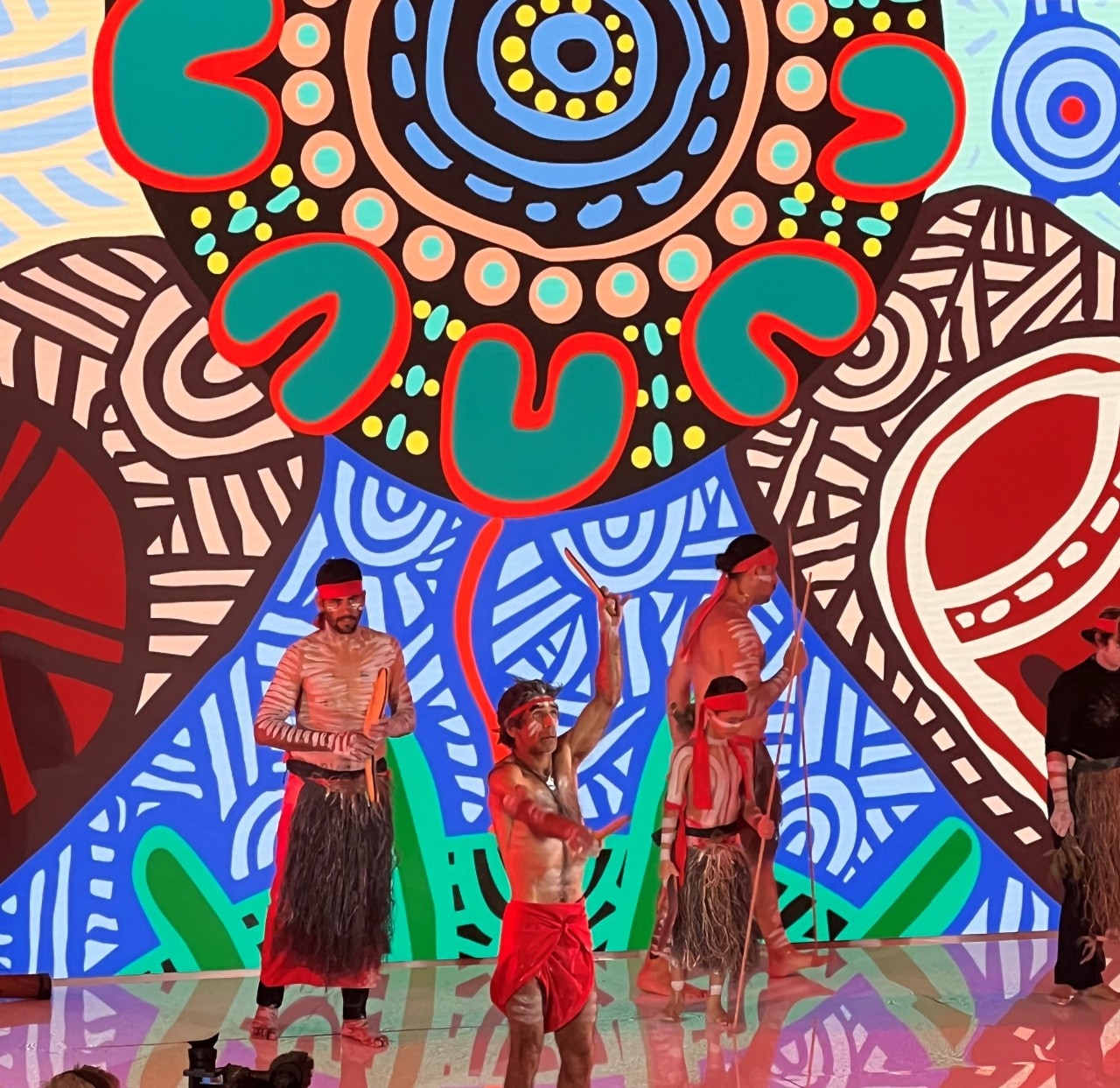

The overall theme of the conference is collaborating for greatness in a multidisciplinary world and that collaboration was very much on display as delegates gathered together to watch the spectacular Welcome to Country by Nulunga Dreaming.

Students Grace Judah and Matilda Langford welcomed the delegation, emceeing the event, while Chief Global Affairs Officer, THE, Phil Baty, and Professor Mark Scott, President and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Sydney, urged the crowd to get ready for a week of conversations and collaboration.

Mr Baty said it had been 10 years since the first summit and in that time close to 10,000 people had connected in person through the signature events.

“I hope amid the serious, stimulating and no doubt challenging conversations we will be having across the next few days that we will also have plenty of times and moments together to celebrate our 10th birthday,” he said.

Professor Scott said it was more important than ever that higher education leaders come together to focus on the great global challenges and noted that partnerships were the key to the future of universities everywhere.

“The ability to work in a multidisciplinary way together within the University and then to find great partners with other Australian universities, international universities, business, government and the nonprofit sector is important - how do we develop a great reputation for partnership?” he said.

He referenced one of his “heroes” in the audience – Professor Rocky S. Tuan, Vice-Chancellor and President of the Chinese University of Hong Kong – who talks about how institutions must “collaborate or crumble.”

“So how do we learn to have great skills enabled to collaborate and to work with each other?” Professor Scott asked the audience, adding that one of the key tenets of the University of Sydney 2032 strategy was to ensure generosity and openness about knowledge and insights, and how to apply those findings in a practical way.

“We want to think about how in this era, we create truly transformational experiences for our students, particularly in a rapidly changing world, particularly in a world that's going to be dominated by AI.

“How do we ensure that the valuable time our students invest with us, gives them a payback that’s truly transformational? We're very keen to make this a truly diverse institution that reflects our broader society.”

Professor Cheryl Regehr

The next generation leadership model

Keynote discussion moderated by Phil Baty, Chief Global Affairs Officer, Times Higher Education with:

- Professor Cheryl Regehr, Provost and Vice-President, University of Toronto

- Misha Schubert, CEO, Science and Technology Australia

- Simone Clarke, Chief Executive Officer, UN Women Australia

In this session the panellists started by sketching out some of their career and leadership journeys before moving into discussing some of the modern-day leadership pathways, noting that leadership is always an evolving process – not a ‘snapshot’ in time that can be boxed neatly.

Professor Regehr stated contemporary challenges for university leaders include economic and ideological constriction and the competition for global talent. But she believes what remains constant is the need for common goals and values which inform universities’ responsibility to civil society, to local community, to students and staff and to how research and university leadership contribute to the world.

The panel agreed that one of the notable differences for leadership, that differs from the recent past, is the speed with which decisions are expected to be made, including in response to the social media cycle. But Professor Regehr commented while universities need to be agile they also have a commitment to ‘collegial governance’ - the widespread consultation that goes with accountability.

Reflecting on speed in the context of values Ms Schubert spoke about the importance of being deliberative about both setting and telegraphing values because they are the basis for good leadership and to creating institutional trust. She explained that in her organisation a commitment to kindness, thoughtfulness and respect was fundamental to how leadership operated.

Ms Clarke, with agreement from the panel, took issue with labelling certain emotional and inclusive skills as ‘soft skills’ still sometimes identified as ‘female skills’. Following applause from the audience, she agreed with the point that instead they should be seen as meta-competencies, that are essential to relationship building within organisations and between them.

Ms Clarke said she needs to remind herself, “You do have time to be nice! Slow down, give time and take time.”

In response to an audience question about the high level of demand often placed on leaders from minority backgrounds to be representative of their communities, panel members acknowledged the fact and the need for a duty of care. They also recognised the fundamental importance of measuring against hard metrics to create more diverse leadership and on the need for inclusivity to accompany diversity. Ms Schubert phrased it as the need for ‘bold ambition’ to get to a tipping point.

Panel discussion featuring Gary May, Chancellor of University of California, Davis.

Leadership reflections: Nurturing diverse talent

Moderated by Professor Mark Scott, University of Sydney Vice-Chancellor and President, in discussion with:

- Gary May, Chancellor, University of California, Davis

- Professor Dawn Freshwater, Vice-Chancellor, University of Auckland

- Professor Colette Fagan, Vice-President for Research, University of Manchester

The panel reflected that diversity, equity and inclusion policies are crucial, and should be a core priority of universities. Nurturing diversity is complex. It requires major change where universities need all the components to fit together like a jigsaw. They also need to challenge group think and orthodoxy. It takes effort, commitment, transparency and boldness. Leadership teams need to listen to people’s ideas and devote resources to deliver changes.

Models to increase diversity need to be written into the strategic plans of universities. Leaders need to demonstrate commitment, as they set the tone for everyone else. Diversity, inclusion and equity should be reflected in the values of the university.

Gary May, Chancellor of University of California Davis, discussed that diversity is undervalued worldwide, despite the demonstrated benefits. He said diversity has better outcomes for universities, and where there is no diversity, there are negative outcomes. Diversity efforts require leadership, but diversity is also a collective responsibility – it’s everyone’s job. UC Davis asks candidates at interview how they have contributed to a diverse environment, and how have they improved the environment? They ensure they hire people who are engaged with diversity.

The panel considered that strategies to nurture diversity include creating a welcoming environment where all people feel valued; reimagining and rethinking job responsibilities to ensure diversity is a priority; shifting to recognising the whole team not just leaders of projects; and ensuring diversity priorities cascade down to the day-to-day leaders to implement change.

Moderated by Professor Lisa Jackson Pulver, Deputy Vice Chancellor (Indigenous Strategy and Services), University of Sydney, in discussion with:

- Professor Cheryl de la Rey, Vice-Chancellor, University of Canterbury

- Professor Meric Gertler, President, University of Toronto

- Professor Catherine Ris, President, University of New Caledonia

- Professor Barry Judd, Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous), University of Melbourne

- Matilda Langford, University of Sydney student

Professor Jackson-Pulver set the scene for this session by reminding attendees that Australia is home to the world’s longest continuous culture. She invited panelists to outline steps they and their institutions had taken to promote the interests of First Nations peoples. Professor Jackson Pulver also asked them to suggest one thing that could be done in the next five years that would have lasting benefits to Indigenous communities.

Professor de la Rey said the welcoming ceremony (powhiri) held for her when she arrived at the University of Canterbury from Pretoria was an opportunity for her to reflect on the meaning of partnership. In recognition of New Zealand’s Treaty of Waitangi she established an Office of Treaty Partnership with local tribe (iwi) Ngai Tahu. She says the university needs to develop a critical mass of Maori academic staff who can help create the different knowledge systems needed to change the world.

After 30 years in higher education, Professor Judd says he still often feels like an imposter in the sector. He pointed to teachers and role models, mostly non-Indigenous, who encouraged him to go to university (he was first in his family to acquire a degree). He said better planning is needed to ensure more people like him are encouraged to succeed in education. Professor Judd said universities should show greater commitment to drawing on Indigenous knowledge and changing what they teach accordingly, measures that will benefit humanity and the planet.

The University of New Caledonia was established 35 years ago to help fulfil New Caledonia’s Closing the Gap policy, said Professor Ris. As a small, young university it has been able adapt its teaching methods to reflect the needs of the country and its Kanak people. She is an advocate of affirmative action and quotas. Professor Ris said her university also has an important role in promoting the role of Indigenous cultures, and continuing to do this will help build students’ confidence.

Professor Gertler said the University of Toronto has worked hard to hire more Indigenous staff. Its program of underwriting the cost of employing Indigenous staff, shifting the cost away from deans, has proved transformative. He believes universities need to pay attention to symbols and signs and cites the Indigenous ‘Eagle Feather Bearers’ introduction at all graduation ceremonies at his University as a positive step.

Matilda Langford is the first in her large family to attend university. She believes affirmative action and quotas are important measures and that universities should better understand that fulfilling cultural commitments is often the top priority for Indigenous students.

Professor Emma Johnston, Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Research), University of Sydney.

Creating a true interdisciplinary environment

Moderated by Professor Emma Johnston, Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Research), University of Sydney, in conversation with:

- Professor Duncan Maskell, Vice-Chancellor, University of Melbourne

- Professor Carolyn Evans, President and Vice-Chancellor, Griffith University

“I had never seen such thick ash, as black as an oil spill, on that beach.” Professor Emma Johnston opened the panel with her observations of the fall out of Australia’s Black Summer bushfires of 2019-2020, which she included in the subsequent, national State of the Environment report.

For the first time, that report was co-authored with Indigenous experts, and it explicitly considered the connections between the environment and human wellbeing.

“Challenges require us to work more effectively across differences,” Professor Johnston said.

Professor Maskell agreed, also using an example from his own career - as an infectious diseases researcher. His novel approach to investigating how diseases transfer from animals to humans in Myanmar encompassed including colleagues from anthropology at the outset. Describing it as a “powerful experience”, he also lamented that, at the time, it was a struggle to attract funding.

Professor Evans, too, celebrated being part of a pioneering movement toward multidisciplinarity. As a student at then “radical” Griffith University in the 1970s, disciplines were largely absent. As Vice-Chancellor, she is once again celebrating that ethos. “I’m pushing on open doors,” she said.

The panellists acknowledged that although there can be structural barriers to working across areas, it is a practice worth pursuing. University research that arose from the pandemic, for example, exemplified its importance. Equally, however, it is on everyday matters that collaboration can make a significant difference. Professor Maskell said: “Universities are about more than solving problems; they are also asking big questions, such as ‘what does it mean to be human?’”

Moderated by Professor Annamarie Jagose, Provost and Deputy Vice-Chancellor, University of Sydney, in discussion with:

- Professor Rocky S. Tuan, Vice-Chancellor and President of the Chinese University of Hong Kong

- Professor Shearer West, Vice-Chancellor and President of University of Nottingham

- Professor David Garza, President of Tecnológico de Monterrey

- Professor David Lloyd, Vice-Chancellor and President of University of South Australia

- Dr Megan Kenna, Executive Director of Schmidt Science Fellows

Professor Annamarie Jagose opened this session on how leadership teams can work with faculties, students and partners to encourage research collaboration, with an amusing piece of advice from a colleague: “You must lower your level of contempt for other disciplines”.

This set the tone for the university leaders to offer some two-minute “hot takes” on the challenges and goals for multidisciplinary research. Professor David Garza suggested providing researchers with an excellent physical space to work in together, stating: “Faculties might fight for money but they will kill for a space.” He suggested the car park, coffee shop and corridors can be where the “magic” happens between researchers. “They need an entire ecosystem and they need to feel they belong to it.”

Professor Rocky Tuan said universities “first, must believe in multidisciplinary research” and likened it to gourmet cooking that incorporates social sciences, agriculture, biology, chemistry, culinary art, presentation and artistry.. “All of life is multidisciplinary. There is a definite need for it.”

Professor David Lloyd said universities need to break down silos and ask new staff members “are you coming to work in my institutions or for my institution – that will determine what path they are on.” He added universities need to address the reward structure suggesting a pathway to being a professor through industry connections.

Professor Shearer West said some of the challenges to multidisciplinary research included internal politics (“we had some very jealous people who felt this investment was coming to them and not to us”). “It can be risky, you have to hold your nerve for outcomes. You need to expect and tolerate failure and deal with it quickly.”

Dr Megan Kenna agreed, stating her work recruits the best and brightest PhDs in the world to work together, but sometimes they report a “lack of community” and they miss the departmental conversations. The incentive structures are a problem for those publishing outside their field: “If you are the first author in expected publications, you were more likely to gain success on the academic ladder.”

Professor Tuan wrapped it up saying universities have inherited an administrative structure that is 1000-years-old: “It started with Aristotle and Plato as teachers and then we had all this divisions and that generates tension. We need to do some rethinking. They are not necessarily just ‘silos’ - they are well meaning. But we need to put our heads together, we could have multidisciplinary ranking, maybe that would solve some of this. We need a top- down approach and a ground up approach.”

Mobilising for disaster response and climate resilience

Moderated by John Ross, Asia-Pacific Editor, Times Higher Education in conversation with:

- Teruo Fujii, President, University of Tokyo

- Annet Nakyeyune, International Institute for Environment and Development

- Ir Nizam, Director General of Higher Education, Government of Indonesia

This session explored how multidisciplinary initiatives can help universities support the work of policymakers, industry leaders and local communities in their efforts to respond to global humanitarian disasters and the climate crisis.

Participants examined the tension between universities as creators of knowledge and their role in bringing civil society together to solve problems with short timelines – heightened during times of natural disaster.

President Teruo Fujii from the University of Tokyo said that the role of the university is evolving as we tackle the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

“As universities we can reach out to [a wide range of social] sectors to drive activity and bring them together to achieve SDGs. This is a new role of the university – to mobilise and spread out to different disciplines and sectors in society...

“That’s why it’s so important to immerse students in a multidisciplinary environment.”

Annet Nakyeyune from the International Institute for Environment and Development said that universities can play a central role in achieving the change we desire in terms of climate action. She said universities play a role in knowledge creation for adaptation innovation and mitigation innovation.

“Universities are power centres for knowledge and [bring] robust method [to partnerships]. However, sometimes partnering with universities doesn’t come easy. We are finding that partnering with universities has advantages … but the benefits of partnership with universities are not always realised.”

She said this is because motivations for universities can be different to that of action-oriented research NGOs.

Ir Nizam, Indonesia’s Director of Higher Education said he was unfortunate to have gone through four or five natural disasters in his professional life.

“We lost 200,000 lives during the 2004 tsunami in Aceh. It was beyond belief what happened on the ground.”

He said that universities are important centres for knowledge creation but what happens on the ground can be different to theory. Universities can [play a role] to bring science and knowledge into solving real problems that are time critical.

“Every disaster is unique and needs a fresh approach. The important thing is that academia can become a catalyst in a messy situation to bring together government, NGOs and local community.”

Federal Minister for Education Jason Clare

Federal Education Minister meets delegates

Federal Minister for Education Jason Clare joined delegates on the lawns of the historic Quadrangle last night to celebrate the end of Day 1 of the Summit and the coming together of the global higher education community.

Minister Clare then welcomed the delegates to Australia and spoke about the important role universities play.

“Great universities, at their core, are about the future. They don’t just focus on today’s problems; they try to anticipate and solve the ones that lie ahead. They are not places of privilege; they are places of opportunity. I looked forward to seeing what comes out of this Summit.”

Welcoming the Minister was University of Sydney’s Vice Chancellor and President, Professor Mark Scott who commented that the Summit was the Higher Education sector’s version of the Olympics and reflected on the “rich and interesting” conversations that had taken place that day. He also thanked former University of Sydney Vice-Chancellor, Dr Michael Spence AC, now President & Provost at the University College London as well as former Deputy Vice Chancellor (Research) Professor Duncan Ivison and former Vice-Principal (External Relations) Tania Rhodes-Taylor, who brought the conference to Sydney.