The Lewis Trilogy is ultimately about a love for theatre

Over five engaging and enjoyable hours, the Lewis Trilogy, three works by Louis Nowra, works insistently to convince its audience it is about love. Love that overcomes, that transcends, that is everything. And there certainly is a lot of love in the room.

Love for outsiders: battered and ruined families scraping sullen lives in the post-war badlands of a northern Melbourne housing commission estate; the dislocated, disjointed patients of a psychiatric institution muddling their way through rehearsals for Mozart’s Cosi fan tutti; flotsam and jetsam misfits carving out a place to belong in the front bar of a harbourside hotel.

Love for theatre: the sharing of stories in a strange little room, an irregular rhomboid set between the steep rakes of benched seating: 120 souls packed in tight, thankful for the companionship (and air conditioning), celebrating the work.

The love of a playwright for his characters. And the love of a man for a woman. Or for many women: “I was”, the narrator reflects at one point, “between divorces”.

A dream to do something

Louis Nowra is one of the most significant Australian playwrights of the past 40 years. His work stretches form and convention beyond realism towards a heightened theatrical lyricism, never losing sight of the textures and cadences of the world.

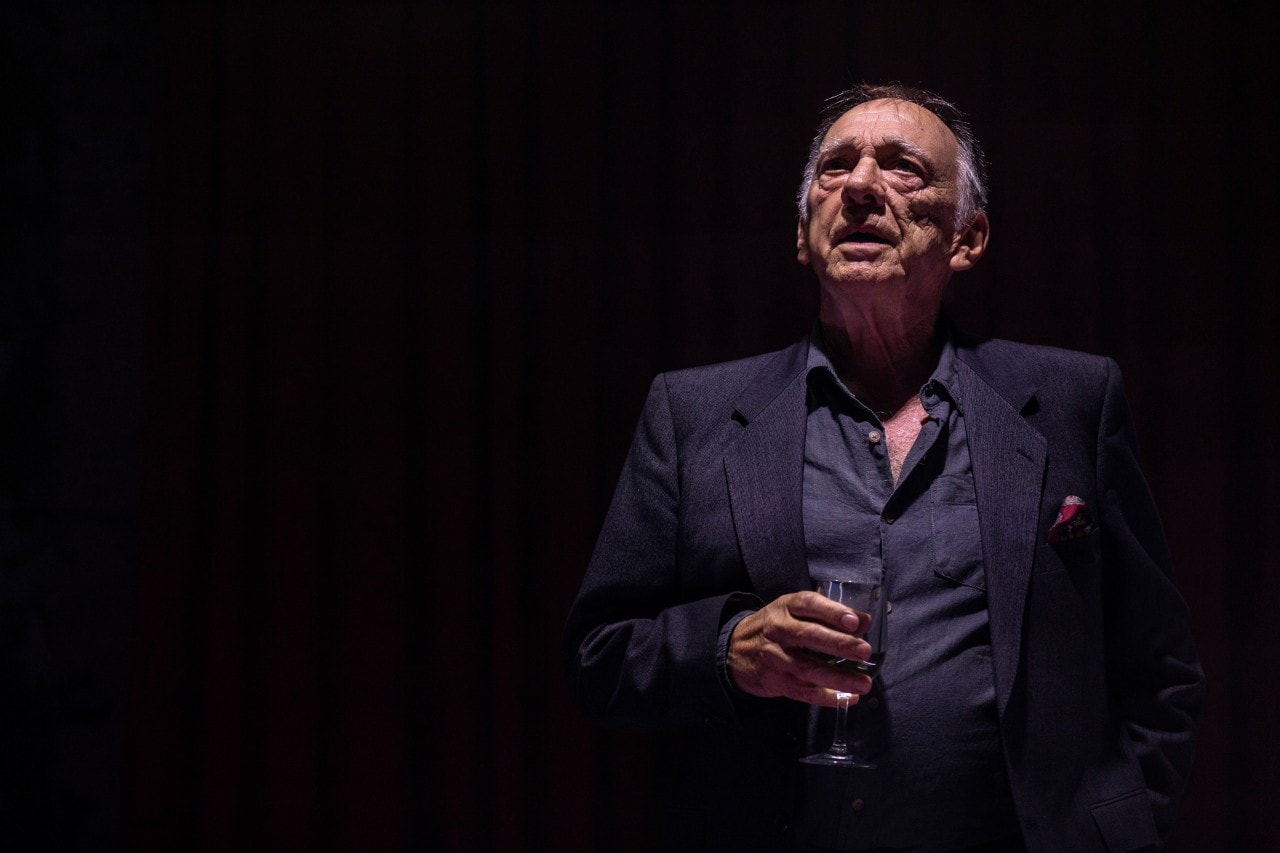

Under the direction of Declan Greene, each play in the trilogy has been trimmed to around 90 minutes. Summer of the Aliens (1992) is first: a coming-of-age drama, a guileless theatre à clef narrated by William Zappa’s warmly-rendered old Lewis, unfolding on the appropriately arid, unadorned boards of the stage, over which looms a flickering cinema hoarding touting a Cold War sci-fi alien invasion film.

Lewis and Dulcie dream of something more: to sprout angel wings, to be kidnapped by aliens, to get away. Photo: Brett Boardman

The action centres on the friendship of the young Lewis (Philip Lynch) with the precociously worldly — and, as we discover, sexually-abused – Dulcie (Masego Pitso), starting with play wrestling and culminating in a booze-fuelled break-in at the local RSL club. Both dream of something more: to sprout angel wings, to be kidnapped by aliens, to get away.

To do something, to be somewhere other than there.

The second play, Cosi (1992), is the most conventionally accomplished of the three. Young Lewis is now an arts graduate and sometime political activist, taking on his first job: directing an opera in an asylum.

Nowra’s writing here is at its most assured. Even in the relatively shortened form, the dramaturgy is assured, the dramatic arc solid. The chaotic menagerie of recovering junkies, pyromaniacs, narcissists and all but catatonics resolves into a sublime, show-stopping set-piece performance of operatic highlights.

Cosi is Nowra’s writing at its most assured. Photo: Brett Boardman.

Finally, the most explicitly reflexive and formally adventurous of the plays, 2017’s This Much is True.

A more-than-affectionate love letter, a late-in-life coming of age story, as the old Lewis (Zappa again) finds his people: a picaresque assemblage of character sketches (the pub itself one of them) and story shards woven into a narrative of loss, yearning, betrayal and redemption.

This Much is True is a late-in-life coming of age story. Photo: Brett Boardman

Old Lewis, now a full-blown character in the world he narrates, explains: when people know that you are a writer, they bring their stories to you. It’s almost an apology for the frenetic, episodic magic realism that has unfolded. This perhaps unreliable narrator assures us, though, that the stories were the ones he had heard about and experienced:

Some of you may think they’re exaggerated, but we locals think otherwise.

A span of life

As relentless as the insistence on love is the insistence of time. The five hours are bracketed by repeated tones, a metabolic rhythm as implacable as a metronome, the tympanic beating of an angiogram. A coiling: love and time; time and love. Themes of death, loss and regret press and surge, pushing back, hard, against the simplicity of the promise of love.

The plays chart a span of life; spending a day in the theatre with the plays redoubles the palpability of time itself. We – the audience – dwell in the power of theatre to immerse us in place and time. Between plays we sit on the kerb outside, have a coffee at a local café, a bowl of pasta or salad, return and smile at our fellow audience members. We move around the theatre, choosing different seats for each play.

The versatile cast includes the outstanding actor Ursula Yovich, right, seated, in a neck brace. Photo: Brett Boardman.

We follow the actors as they move through different roles, catching echoes and tensions across the casting: Paul Capsis tears it up as a series of wild-eyed clowns; Thomas Campbell finds pathos and subtle variations through a motley collection of blokes (and others).

Ursula Yovich is utterly compelling, first as young Lewis’ grandmother, then as an adoring psychiatric patient, and finally as a standover man. Her presence on stage gently but unmistakably alerts us to the absence of First Nations people in a play cycle so concerned with place, community and belonging.

Lynch is extraordinary as the young Lewis in the first two plays: a glorious portrait of a young man finding his feet.

Pitso has the toughest gig. The burden of Lewis’ yearning, regret, and, yes, love, falls on her characters’ shoulders. Photo: Brett Boardman

Pitso, though, has the toughest gig: first as young Dulcie, then as a recovering junkie, and finally as a philosophy student working as a barmaid in the Rising Sun Hotel. The burden of Lewis’ yearning, regret and, yes, love, falls on these characters’ shoulders.

In a rewriting of the final scene, Nowra has crafted a more emphatic narrative arc, binding the trilogy all the more tightly together: Dulcie, old Lewis explains, was something like the one true love. It was always Dulcie for whom he was looking, who he needed to save.

A neat piece of dramaturgy, but, for me, something of a deflation after an otherwise deeply, resonatingly rich immersion.

The Lewis Trilogy is at Griffin Theatre Company until 21 April, 2024. All photos supplied by Griffin Theatre Company.

Associate Professor Ian Maxwell is Chair of Theatre and Performance Studies. This story was first published in The Conversation.