A once-dormant magnetic neutron star is emitting strangely polarised light

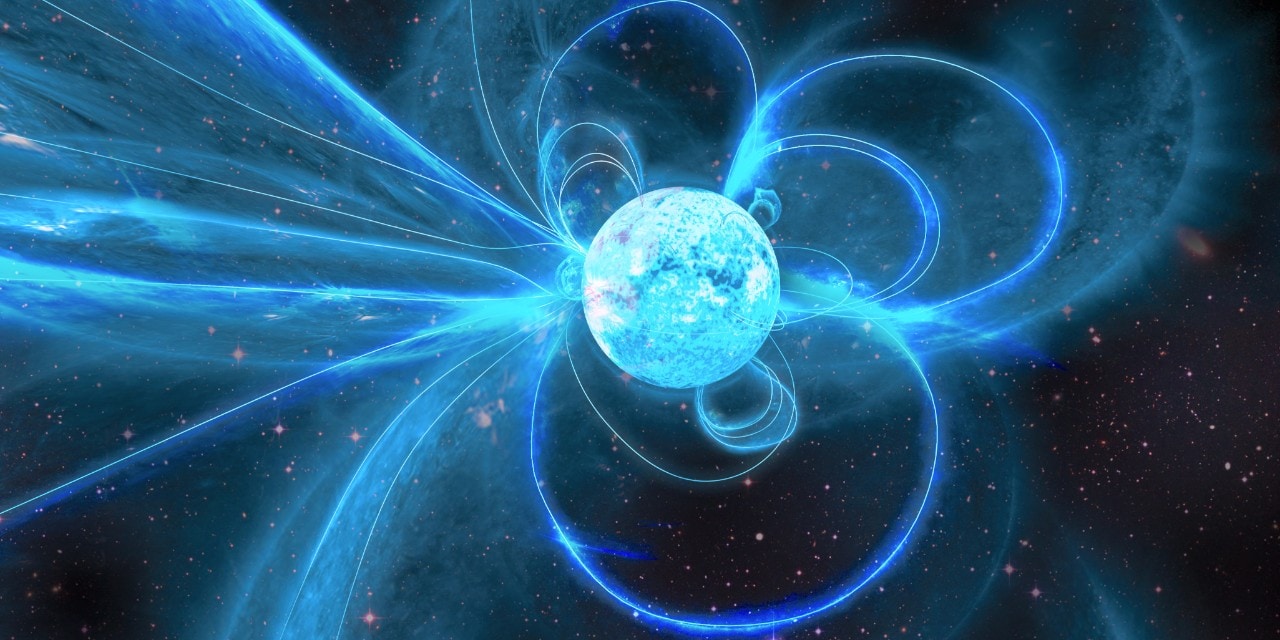

Artist's impression of a magnetar. Credit: Carl Knox, OzGrav/Swinburne

Astronomers using Murriyang, CSIRO’s radio telescope at Parkes NSW, have detected unusual radio pulses from a previously dormant star with a powerful magnetic field.

New results published today in Nature Astronomy describe radio signals from magnetar XTE J1810-197 behaving in complex ways.

Magnetars are a type of neutron star and the strongest magnets in the Universe. At roughly 8000 light years away, this magnetar is also the closest known to Earth.

Most magnetars are known to emit polarised light, though the light this magnetar is emitting is circularly polarised, where the light appears to spiral as it moves through space.

Dr Marcus Lower, a postdoctoral fellow at Australia’s national science agency CSIRO, led the research and said the results are unexpected and totally unprecedented.

"Unlike the radio signals we’ve seen from other magnetars, this one is emitting enormous amounts of rapidly changing circular polarisation. We have never seen anything like this before,” Dr Lower said.

Dr Manisha Caleb.

Co-author Dr Manisha Caleb from the School of Physics and University of Sydney Institute for Astronomy said studying magnetars offers insights into the physics of intense magnetic fields and the environments these create.

"The signals emitted from this magnetar imply that interactions at the surface of the star are more complex than previous theoretical explanations,” she said.

Detecting radio pulses from magnetars is already extremely rare: XTE J1810-197 is one of only a handful known to produce them.

While it’s not certain why this magnetar is behaving so differently, the team has an idea.

Artist's Impression of a magnetar

Audio is translation of radio data. NB: not from magnetar in this study. Source: CSIRO

“Our results suggest there is a superheated plasma above the magnetar's magnetic pole, which is acting like a polarising filter,” Dr Lower said.

“How exactly the plasma is doing this is still to be determined.”

XTE J1810-197 was first observed to emit radio signals in 2003. Then it went silent for well over a decade. The signals were again detected by the University of Manchester's 76-metre Lovell telescope at the Jodrell Bank Observatory in 2018 and quickly followed up by Murriyang at Parkes, which has been crucial to observing the magnetar’s radio emissions ever since.

Murriyang CSIRO's Parkes Radio Telescope. Source: CSIRO

The 64-metre diameter telescope on Wiradjuri Country is equipped with a cutting-edge ultra-wide bandwidth receiver. The receiver was designed by CSIRO engineers who are world leaders in developing technologies for radio astronomy applications.

The receiver allows for more precise measurements of celestial objects, especially magnetars, as it is highly sensitive to changes in brightness and polarisation across a broad range of radio frequencies.

Studies of magnetars such as these provide insights into a range of extreme and unusual phenomena, such as plasma dynamics, bursts of X-rays and gamma-rays, and potentially fast radio bursts.

Research

Lower, M, et al, ‘Linear to circular conversion in the polarized radio emission of a magnetar’, Nature Astronomy, vol 8 (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-024-02225-8

Acknowledgement

The researchers acknowledge the Wiradjuri People as the traditional custodians of the Parkes Observatory site where Murriyang, CSIRO’s Parkes radio telescope, is located.

Declaration

The authors declare no competing interests. Research was funded by the Australian Research Council, National Natural Science Foundation of China, Dutch Research Council.