Australia's 'Easter bunny', the bilby, has had its genome fully sequenced

Professor Carolyn Hogg in the laboratory.

A consortium of scientists led by the University of Sydney has for the first time sequenced the entire genome of the Australian bilby.

This first mapping of the bilby’s genetic blueprint, encapsulating biological information on how they grow and evolve, provides an important tool for conservation of the threatened species.

Lesser known than other marsupials, bilbies are often referred to as the Australian Easter bunny and have ongoing cultural significance to Aboriginal Australian communities.

Notable for their large ears and backward facing pouches, bilbies are burrowing nocturnal omnivores. They use their strong forelimbs and long claws to find food and turn over soil and organic matter, making them the ecosystem engineers of Australia’s deserts.

Bilby. Photo: Yuanyuan Cheng.

There were once two bilby species, the Lesser bilby, which became extinct in the 1960s, and the Greater bilby that now exists in only 20 percent of its former habitat range, mostly in the central deserts of Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

Bilby populations went into steep decline after European arrival and the introduction of feral cats and foxes, as well as rabbits competing for food sources. Bilby populations are often managed in the wild by Indigenous rangers, while about 6000 live in fenced sanctuaries, islands and zoos.

Using DNA from a deceased zoo bilby, a team led by the University of Sydney’s Professor Carolyn Hogg has sequenced the genome of the surviving Greater bilby. The team also created the first genome for the extinct Lesser bilby from the skull of a specimen collected in 1898.

“The Greater bilby reference genome is one of the highest quality marsupial genomes to date, presented as nine pieces, representing each of the bilby chromosomes,” said Professor Hogg from the Australasian Wildlife Genomics Group. “It offers insights into biology, evolution and population management.”

A reference genome is the equivalent of having a puzzle box lid; it’s a way of knowing what all the DNA puzzle pieces mean.

“It helps us understand what gives bilbies their unique sense of smell and how they survive in the desert without drinking water,” Professor Hogg said.

The Greater bilby genome comprises of about 38,000 protein coding genes across nine chromosomes with 3.66 billion base pairs. By comparision, the human genome has about 19,900 protein genes across 23 chromosomes with 3.2 billion base pairs.

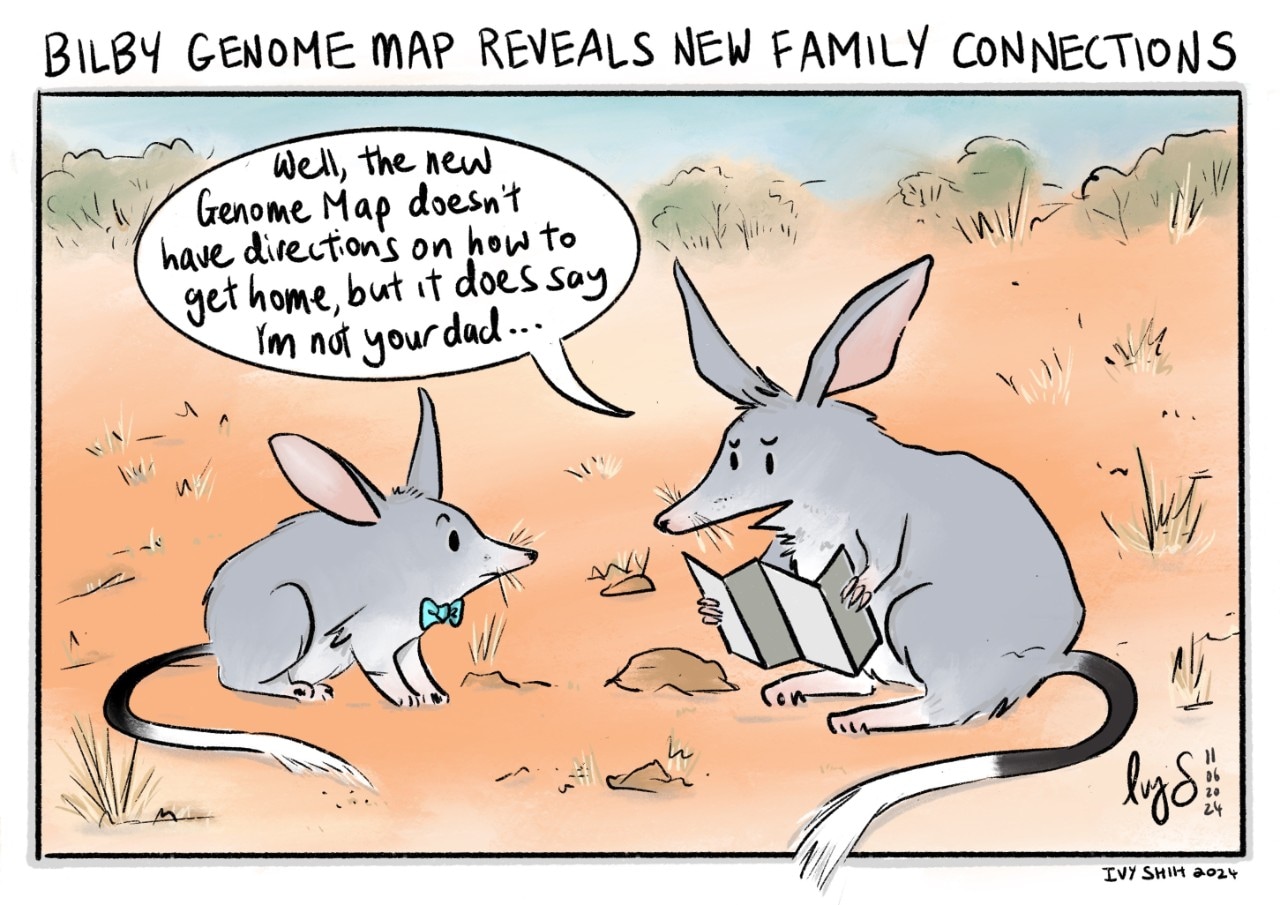

Cartoon by Ivy Shih.

Importantly, the genome is being used to manage the bilby metapopulation in zoos, fenced sanctuaries and islands.

“By selecting individuals for translocation and release we maximise their genetic diversity, thus improving the population’s ability to adapt to a changing world.”

The team has also used the genome to develop a more precise scat testing method to complement existing traditional land-use practices by Indigenous rangers.

“We know a lot about bilbies – where they live, what they eat, and how to track them,” said ranger Scott West from the Kiwirrkurra Indigenous Protected Area in Western Australia.

“It’s good to use iPads for mapping, and cameras to monitor them. The DNA work also helps check if bilbies are related, where they are from and how far they travelled. Using old-ways and new-ways together helps us get good information about bilbies and how to look after them. This is what two-way science is.”

“Everything takes four times longer and is four times more difficult when you don’t have a reference genome,” Professor Hogg said. “We have accelerated science to ensure the ongoing survival of bilbies.”

Ranger Scott West, Kiwirrkurra Indigenous Protected Area in Western Australia.

Research

Hogg et al. ‘Extant and extinct bilby genomes combined with Indigenous knowledge improve conservation of a unique Australian marsupial.’ Nature Ecology & Evolution DOI: 10.1038/s41559-024-02436-2

Bilby joey in pouch. Photo: Save the Bilby Fund.

Declaration

The authors declare no competing interests. The research was supported by the Australian Government’s National Collaborative Research Strategy’s (NCRIS) Bioplatforms Australia Threatened Species Initiative and the Australian Research Council through a Discovery grant and the Centre for Excellence in Peptide and Protein Science.