Helping swimmers get off to a flying start

As the world's best swimmers hit the pool in Rio, new University of Sydney research is showing how athletes can make a bigger splash with their dive.

Just like athletics, competitive swimming races begin with an auditory starting signal, yet little is known about how swimming start reaction times are affected by auditory stimulus training in the sport.

Now, a Research Masters candidate from the Faculty of Health Sciences, Christopher Papic, has examined whether specific dive training for these acoustic cues can improve reaction time and subsequent race performance.

"The majority of competitive swimmers do not currently complete habitual dive training with the same auditory stimuli used to commence a swimming race," said Papic.

"Swimmers are relying on their reflexes in competition after hours of practice dives without audial guidance. This can lead to a slower initiation of force being applied through the block and poorer starting times when it comes to actual racing conditions."

Can dive training with a buzzer improve reaction times?

To investigate whether dive training to aural prompts resulted in improved performance, Papic observed 10 adolescent New South Wales state-level swimmers, as part of his Masters thesis.

The swimmers were split into two separate four-week dive training programs; one without auditory stimulus during dive training, and the other with competition-specific auditory stimulus dive training.

Papic and his supervisor Professor Ross Sanders compared the swimmers' reaction time, block time – the time from the starting buzzer until the last moment of contact with the block – and 'time to 15 metres' before and after the training period, using a custom-made force measurement device and a high-speed camera. Reaction time was measured as the first moment of muscular activation in response to the 'go' signal, even before visible movement occurred.

Following the four-week period, the swimmers who received auditory stimulus dive training achieved the fastest reaction times, shaving around 0.012 seconds off their speed on average, compared with regular dive training swimmers, who actually revealed slower reaction times than before the training period commenced.

"Swimmers who did not receive competition-specific audial cues as part of their training programs exhibited slightly slower reaction times from pre- to post-intervention," said Papic.

"Every bit counts, especially in a sport that records race times to the nearest hundredth of a second. However, while auditory stimulus training can improve reaction times at the start of the race, its contribution to overall performance was much more modest and further research is necessary in order to fully investigate the effects of this form of race preparation."

Every bit counts, especially in a sport that records race times to the nearest hundredth of a second.

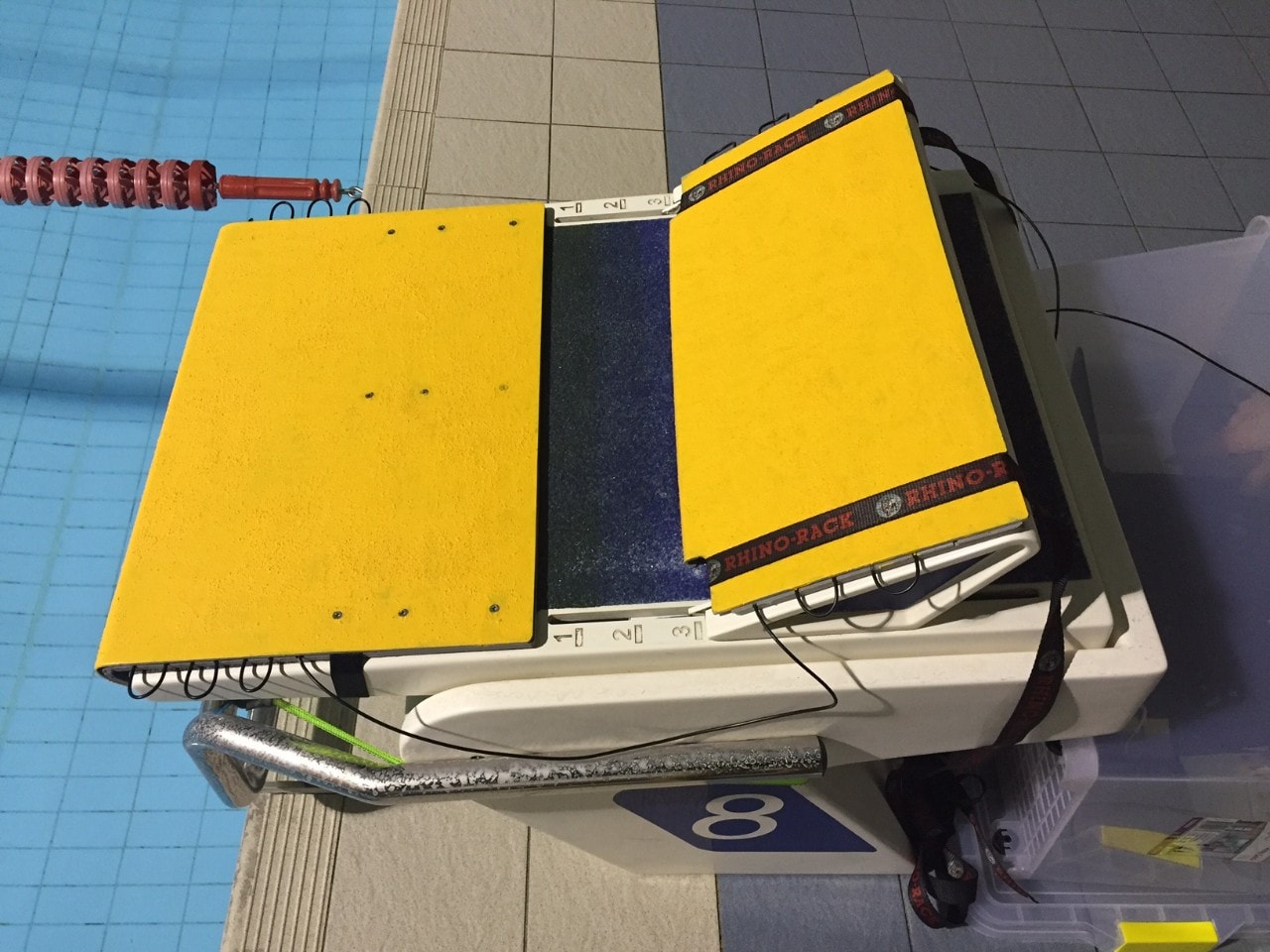

Masters candidate Christopher Papic's custom-made force measurement device helped researchers record diving reaction times.

Swimmers showed faster reaction times than Athens athletics starts

Surprisingly, Papic and his team also discovered that swimmers in the auditory stimulus training group showed faster average reaction times than that of 100m track sprinters at the Athens Olympics. The swimmers had an average reaction time post-intervention of 0.119 seconds, while male Olympic sprinters had an average of 0.164 seconds and female sprinters of 0.184 seconds during the Athens Games.

"The fact that the swimmers' reaction times were faster than track athletes in competition raises the possibility that there may be a further neural processing 'barrier'," said Professor Ross Sanders, who is Head of the Discipline of Exercise and Sport Science.

"This extra layer of processing may be associated with fear of disqualification due to false-starting (reaction times less than 0.100 seconds). Yet swimming does not have a clear false start mechanism like athletics, and this may be attributing to the swimmers' faster reaction times."

Papic and Professor Sanders plan to use their custom-made reaction time device to conduct further swim training research, with the new tool providing exercise scientists and coaches a cheaper and more precise method of reaction analysis.